| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

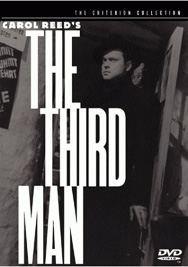

The Third Man The Third Man

The Third Man Criterion 64 1949 / B&W / 1:33 flat full frame / 104 min / Street Date November 30, 1999 / 39.95 Starring Joseph Cotten, Alida Valli, Trevor Howard, Orson Welles, Bernard Lee, Ernst Deutsch, Wilfrid Hyde-White, Alexis Chesnakov Director of Photography Robert Krasker Art Director Vincent Korda Editor Richard Marks Music Anton Karas Original Story and Screenplay Graham Greene Producers Alexander Korda, David O. Selznick, London Films Producer and Director Carol Reed

Once again Criterion has come through with a really special DVD. The Third Man has never been difficult to see, but decent copies of it were rare even for theatrical exhibition. I showed it to my family from AMC a couple of years ago, and the sound and picture were just as bad as Criterion's original laser disc, with blurry, jumpy video and a garbled soundtrack. Certainly one of the best English films ever made, The Third Man can now finally be seen in all its B&W glory.

The critical reputation of Sir Carol Reed suffered in the sixties as the new generation of hip English directors swept away the old guard that Reed represented. (Notable survivor: David Lean) The Third Man told a linear story with no radical cinematic innovations, and critics began insinuating that Orson Welles was somehow responsible for the film's look, its style, even its eccentric zither music track. Critics lauding the inventive anarchy of merry men like Richard Lester would use Carol Reed to personify the stuffy old school, calling his tilted-camera 'Dutch angle' shots a cheap gimmick. Baloney. The Third Man works wonderfully. Its vivid B&W images and Dutch angles are only one aspect of a delightfully baroque visual and aural feast that makes it a good convincer for those who only accept movies in color. The amazing night exteriors are lit almost identically as those of the bleak Night and the City, made in London around the same time. But the Vienna presented here is not a nightmare world of Film Noir. It's a gay European town gone sour, spoiled and rotting. Bombed to bits, its inhabitants eke out their livings in any way they can. Old men sell balloons and a Baron plays violin for restaurant patrons. Much of the great beauty of Vienna is intact - some of the apartment interiors are lavish by American standards, even if their inhabitants can't find a square meal. Anna is a stage actress whose theater has excellent costumes but can't afford to keep the electric lights burning. The Evil in The Third Man is not the fatalism of Film Noir but the social rot that follows any great catastrophe when opportunists capitalize on political confusion. Corruption festers in situations of hopelessness, where moral rules seem no longer to apply. Graham Greene's letter-perfect script is the real star. Many Greene novels would be adapted for the screen, but few as well as The Third Man. Most are okay films that just miss the mark of greatness (Our Man in Havana), and some are just plain disasters (the 50s version of End of the Affair) due mostly to producer attempts to alter Greene's world-weary, sometimes defeatist mood. Here Greene's grim Vienna is enlivened with rich humor, a breakneck pace and endearing characters. A sinister Baron appears holding a copy of a silly cowboy book. Martins refers repeatedly to Calloway as 'Callahan' to insult him, but is broken-hearted when Anna repeatedly calls him Harry instead of Holly. Bernard Lee (James Bond's 'M') is given a stock police goon role that turns out to be the most sensitive and gentle character in the script. Finally, Greene really understands how to construct a thriller, even when cribbing from Hitchcock's The 39 Steps. Nothing could be funnier than the potentially murderous cab ride that whisks Holly into an excruciatingly humiliating literary meeting. "Do you believe in the stream of consciousness?" a man asks, and 'author' Holly doesn't know what he's talking about. In 1949 The Third Man hit its mark because it painted a compelling picture for audiences who couldn't comprehend what the fuss was in Europe. Like Berlin, Vienna was an internationally occupied city divided into zones and policed by a joint multinational force. Cooperation was a cold formality between victors already politically divided. In The Third Man, English policeman Trevor Howard walks a tightrope trying to deal with his opposite number, Brodsky, who appears to be harboring criminal Harry Lime in the Russian sector. Perhaps the best way to 'place' The Third Man (TM) for a younger audience is to compare it to the better-known Casablanca, (C). C is also about an aloof profiteer, Rick Blaine, who is deeply involved with displaced persons, corrupt officials and political confusion in wartime Morocco, where French autonomy is an illusion indulged by Nazi overseers. Claiming cynical detachment, Rick instead makes a commitment to idealism and sacrifices his romantic future with the love of his life so the world can defeat Evil and Utopian Peace can prevail. TM shows how the sentiments and idealism ofC have soured in the postwar situation: Rick's counterpart is the equally suave but morally inverted Harry Lime. Both keep their illegal activities (gambling, black marketeering) functioning with payoffs to officials of questionable authority (Renault / Brodsky). In C, the risks taken by Rick, Elsa and Renault are in tune with the larger drama being played out between the Axis and the Allies. This 'ideological security' helps them make painful personal decisions based on absolute faith in their moral cause. By contrast, Martins, Anna and the late Harry Lime of TM drift in a moral limbo where such absolutes no longer exist. The Allies have 'won' but Vienna has become a new kind of political mire with its own conflicting ideologies and injustices. The gamblers, black marketeers and corrupt French of Casablanca are closet patriots that spend their leisure time helping refugees and secretly opposing the Nazis. In this postwar Vienna, Harry Lime's gang routinely commits obscene, indefensible crimes. Their profit motive shows no regard for their innocent victims, who are considered expendable 'suckers.' In the wartime C, the characters may be confused, but they are ennobled by patriotism and able to make wise and noble decisions. Patriotism is dead in the Viennese ruins of TM. Even the benign characters are so disillusioned they can barely function. Holly waffles and plays at romance like a schoolboy. Anna drifts from bitterness to suicidal despair. 1 Amoral, dog-eat-dog postwar conditions have transformed petty crook Harry Lime into a monster willing to kill children for profit, who can rationalize extermination if he doesn't have to be personally involved. The outcome of WW2, with each victor grabbing all the territory and influence it can get, has shown Harry that the only real interest is self-interest. It's not exactly a romantic or sentimental idea, but one that shows how the world changed from 1941 Casablanca to 1949 Vienna. If WW1 killed off the idea of chivalry and noblesse oblige, then WW2 exterminated the concepts of national patriotism and the ascendancy of human values. The Third Man's 'romantic' conclusion is almost a parody of the grand finale to Casablanca. It's a classical setup: Holly's done the right thing as nobly as a hero from one of his own pulp Westerns. He loves the girl and has tried to protect her. But villains inspire as much devotion and loyalty as do heroes, and a valueless heart has no mercy and no forgiveness. The world won't always welcome lovers, as time goes by... For an ending, Anton Karas' zither music seems to be laughing at Holly, serenading his obsolete romanticism as the leaves fall on the empty road around him. A flawless production, The Third Man boasts perfect casting, some of it accidental. Both Joseph Cotten and Alida Valli were fresh from the Selznick flops Portrait of Jennie and The Paradine Case so they were probably being loaned as Selznick's contribution to the production. Orson Welles more likely than not participated to help finance his own hapless series of shoestring independent productions. With very little onscreen time he manages to invest Lime with a completely credible dimension of suave Evil. That Welles respects the part and director Reed is obvious because he neither affects a strange accent nor concocts one of his phony fake noses to amuse himself. Harry Lime is a charming, slippery, untrustworthy scoundrel ... a persona Welles had little difficulty adopting! Criterion's The Third Man is far superior to any previous video incarnation. Vienna is a baroque fairyland where almost every image in the cobblestoned ruins, the drawing rooms or the cavernous sewers is an eye-opener. The blacks are rich and the image as clean as a whistle, with only the slightest wear at changeover points. The mono audio is clear and the fast-paced English dialog easy to understand. And that amazing zither music is a joy to listen to, even with one's eyes shut. Criterion has included an exhaustive selection of extras, starting with a corny Selznick trailer from 1950 and an equally useless 'prestige' reissue trailer from 1999. Peter Bogdanovich is interviewed and gives some useful background on the film. There is a dandy selection of photos and two unique film clips: One of Anton Karas playing his zither (the instrument doesn't look like what I expected) and a newsreel lauding the Vienna sewer police as they patrol what seems to be an endless underworld of waterways. The alternate American opening voiceover read by Joseph Cotten is also included. But most impressive are the radio supplements. Graham Greene's original treatment is read aloud by actor Richard Clarke on one track, and two entire radio shows are included. Orson spins the Lime character into more of a Rick Blaine hero for the 'Harry Lime' radio serial ... like all of Welles' radio work, it is really well done. Criterion's The Third Man DVD is one of their best. The restoration is excellent and the movie itself a must-see (and a must-hear). For those of you who remember the crummy 16mm prints from college film courses, this is going to be a special treat!

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor, The Third Man rates:

Footnote:

1. Star Alida Valli was chosen for her role in The Paradine Case precisely for her cold sensuality, the feeling that great crimes could coexist with gentleness in that mysterious face of hers. The Third Man makes good use of this quality. Is Anna Harry Lime's innocent dupe? She doesn't seem shocked when confronted with his crimes. Is she romantically schizophrenic, denying her complicity with Harry, yet suffering for it with bouts of depression? Her remorse seems focused only on her personal loss, and not on any moral culpability. Or has the war simply made her completely and selfishly amoral, incapable of involvement in anything beyond her own survival and self-interest? A later Valli role in the horror film Les yeux sans visage, presents a mystery woman who helps kidnap, mutilate and murder young girls at the bidding of a mad doctor. Her exact motivation, indeed her exact relationship with the doctor is never made explicit, yet the character is completely credible, evoking thoughts of what kind of women were employed as workers in Nazi extermination camps. Without the extraordinary qualities Ms. Valli brings to The Third Man, Anna's mysterious relationship with Harry Lime would be a real problem for the film. DVD Savant Text © Copyright 1999 Glenn Erickson

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |