| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Visionaries

Reviewed at the 2010 Tribeca Film Festival

Chuck Workman knows his way around movies; for years, he's been the guy who cuts the montages for the Academy Awards telecast, and he won one of those golden boys himself for 1986 film montage short Precious Images. He also made an amazing feature-length doc called The First 100 Years: A Celebration of American Movies, and I know, I know, the rights issues have got to be a nightmare, but seriously, let's get that thing out on DVD. At any rate, that film was a retrospective of mainstream studio filmmaking; for his new documentary Visionaries, he flips it around and profiles the experimental film subculture.

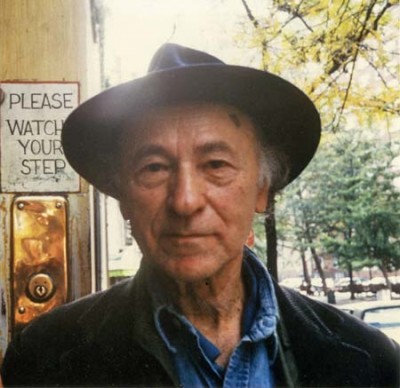

Subtitled "Jonas Mekas and the (Mostly) American Avant-Garde Cinema," it is a comprehensive history of the underground cinema movement, all the way back to the earliest filmed images, back to the surrealists and the early experimental films (Un Chien Andalou, The Man with the Movie Camera, Zero For Conduct) and formative influences like Maya Deren. But his focus is on the art film movement that popped up in the 1950s and 1960s ("The New American Cinema"), and its practitioners: Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, Andy Warhol, Jack Smith, Peter Kubelka, Norman Mailer (briefly), Robert Downey (Senior), and Mekas, the filmmaker, Village Voice and Film Culture writer, and founder of New York's invaluable Anthology Film Archive.

Workman trots out clips from all of them, and while some of them are too briefly seen (the chopping up of the continuous-shot Wavelength sort of defeats the purpose, and I personally would have enjoyed watching the audience shift uncomfortably through more than a moment or two of Warhol's Empire or Sleep), most are strikingly well-used. Workman seizes on the evocative quality of those beat-up, washed out images, and bounces them off each other nicely; his transitions are smooth, the film's sections well-constructed. Some of the clips are jarring and thrilling, others are goofy and laughable. But they're all fascinating--burning with energy and passion--and they are sometimes, at the same time, unbearably pretentious, more important for what they were saying or standing against than for any qualities they possessed in and of themselves.

And frankly, the same can be said of some of the filmmakers. Downey comes across as candid, frank, and funny, as does Mailer (in what looks to be one of his final interviews). Mekas, while often pushy in print, is a warm and engaging patron saint on camera--Workman was wise to put him in the center of the picture. But Anger, for example, is one of those blowhards who proudly announces he doesn't have a phone or a TV, as if he's used to being applauded for it. That kind of high-horse pomposity may have as much to do with why these films remained on the fringe; people don't like being looked down on. What's worse, Workman engages in the same kind of hauteur later in the film; he takes his camera to the Anthology Film Archive and interviews some young movie makers who are there as part of the annual 48 Hour Film Project. It's bad enough that he trots out that ancient documentary device of interviewing random people on the street and asking them about his subject; we're expected to tsk-tsk and shake our heads sadly because these twentysomethings, guilty of nothing except being hungry young filmmakers, don't know who Mekas or Brakhage are. It's a mean-spirited scene, snobbish and irritating--and even more so when, a couple of scenes later, Workman turns around and idolizes the wine-drinking aristocrats, pontificating pompously about film as art at a fancy gallery opening inside the Archive. Who appointed these people the arbiters of good taste? And did anyone bother to ask those kids who their influences were?

There's still plenty to admire in Visionaries; Workman unearths some good clips (including student films by the likes of Orson Welles and David Lynch), grabs some fine interviews, and puts together opening and closing montages that are stunningly well-crafted (it should be noted, however, that the editing of the interview sound in the print I saw was awfully clumsy). The avant-garde filmmakers joined forces to create "a democratic cinema," and when Visionaries is honoring that, it stirs and fascinates. And it has a message that any film lover can get behind: when asked how he manages to do so much, Mekas smiles, "I survive on wine, women, and song... plus cinema." Amen to that.

Jason lives in New York. He holds an MA in Cultural Reporting and Criticism from NYU.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||