| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

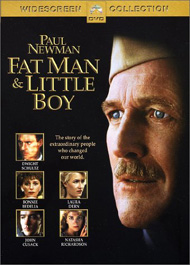

Fat Man and Little Boy |

|

Fat Man and Little Boy Paramount 1989 / B&W / 1:85 anamorphic 16:9 / 127 min. / Street Date April 27, 2004 / 14.99 Starring Paul Newman, Dwight Schultz, Bonnie Bedelia, John Cusack, Laura Dern, Ron Frazier, John C. McGinley, Natasha Richardson, Ron Vawter Cinematography Vilmos Zsigmond Production Designer Gregg Fonseca Art Direction Larry Fulton, Peter Landsdown Smith Film Editor Francoise Bonnot Original Music Ennio Morricone Written by Bruce Robinson, Roland Joffé Produced by John Calley, Tony Garnett Directed by Roland Joffé |

The making of the first atom bomb is a whale of a story, one probably too complicated to tell in a movie. Fat Man and Little Boy tries to give us a reasoned picture of the conflict between the hawkish General Groves and the liberal J. Robert Oppenheimer and ends up doing neither of them justice. The emotional turmoil of characters debating the truth of war, politics and the future of their super weapon is informed too patly by 1989 hindsight to be compelling. With key facts about the Manhattan project shuffled to force a dramatic arc into the story, there's not enough here we feel we can trust.

Handsomely shot by Vilmos Zsigmond and directed well enough by Roland Joffé, Fat Man and Little Boy falls into the trap of mainstream films about complicated and politically loaded subjects -- it must waste too much effort making keeping the mental 8 year-olds in the audience aware of what's going on. That doesn't leave enough time to be more than superficial on other counts. The script touches a lot of bases but avoids making up its mind about any of the issues involved, and the final third of the film is a painfully self-important series of arguments about lofty moral questions.

The Manhattan project is such a tough story to tell as entertainment that Fat Man and Little Boy may be about as good as it can get. It's terribly easy to follow, with voiceovers reading from diaries and war news coming out of Public Address systems as in the lame Swing Shift. The science never gets any farther than the idea of a controlled implosion instead of a cannon, illustrated with the visual of a scientist squeezing an orange so we all get the idea. There's a heck of a good illustration of what a bad nuclear accident can do to a luckless human being. What we mostly learn is that great scientific advances can happen by penning a bunch of eggheads into a confined space and worrying a lot.

Simplified arguments for and against using the bomb get a massive workout here, with some scientists putting forth a petition for a demonstration instead of a direct attack on Japan. Fat Man and Little Boy never really prevaricates on the issues. A lot of the Europeans contributed to the project for fear that Hitler would get the bomb first, but then questioned why it had to be built when Germany fell and Japan was near defeat anyway. That one's going to be argued forever.

The script fifty years' worth of historical hindsight and disclosures into the conflict, and still opts for a "Gee, wasn't it a puzzle?" conclusion. Oppenheimer's unhappy wife Kitty (Bonnie Bedelia) thinks the science boys are too hard at work just trying to kill things. Although the Army chants rhetoric about the untold losses expected in the invasion of Japan, they seemingly want the bomb dropped because to make the Japanese rue the day they dared attack the U.S.. They also aren't keen on explaining where two billion taxpayer dollars went, if it didn't "win the war." (Gee, today nobody worries about 50 billion.) Oppenheimer breaks the stalemate by arguing that a nuclear demonstration for the Japanese observers could fail and make invasion even more difficult.

Fat Man and Little Boy is a "soft" liberal picture that paints the birth of the bomb as a bad thing yet is too chicken to say what made it bad, i.e., the post-war politics that turned the country into a Cold War furnace of fear and aggression. The picture refuses to acknowledge that Oppenheimer was truly left leaning -- we get scientists playing a Russian tune on a piano but professor O. is painted as nothing more radical than a moral elitist who left his heart with his Pinko mistress in San Francisco. Nowhere is there a hint of espionage going on. General Groves is gruff and suspicious, but with his responsibility he had no choice but to be concerned about a group of super-intellectuals whose ultimate loyalty is to humanity and not the U.S. of A. The brass cruelly squelches the scientists' anti-attack petition, and after Groves uses mild blackmail, Oppenheimer too.

To really cook the stew, Fat Man and Little Boy creates a martyr to liberal decency in the John Cusack character. Everything about his romance with Laura Dern is above criticism performance-wise, except maybe the weird behavior of doctor Frazier (Peter de Silva), who seems to prefer a chimpanzee to Dern. Serving as the picture's liberal conscience, Cusack's Merriman character writes a diary for Dad explaining his war service, and serves as the courier for the peace petition to the "radical" scientificos in Chicago. Merriman is set up for tragedy by a familiar war-movie cliché: remember, if you ever find yourself a character in a war movie, never but never openly talk about the great future you're going to have after the war is won. When Merriman receives a massive exposure to plutonium, he works out his own doom in a chalkboard equation before plumping like a hot dog in a microwave -- frying from the inside out. It's pretty scary to contemplate being horribly sunburned, not just on one's skin but in every tissue throughout one's entire body...

I've read that the terrible nuclear accident that this is based on actually happened a year after the war. Placing it earlier serves the film's cautionary message by preventing the successful first bomb test from being a jubilant occasion. Inter-cutting the final bomb preparations in parallel with Merriman's awful suffering unfairly taints the test as an equally sick tragedy. The movie isn't prepared to really condemn the bomb project or nuclear power, so the injection of this awful accident is for naught: don't worry, Merriman, we'll always remain, uh, concerned about your suffering.

History takes over at the finish. The future careers of Oppenheimer and Groves are dismissed in quick text blurbs, as in American Graffiti, as if we already know what happened to them. The postwar race toward nuclear barbarism shoved Groves aside as bigger hawks horned in on the Army's newest toy. Oppenheimer was crucified for being a moral man when anything less than rabid patriotism was considered traitorous.

Those stories are just too controversial to find a mass audience, as any honest reading of the facts would naturally betray a bias or express an opinion. Face it, there's no way to be "fair and even" when discussing someone like Edward Teller, the better-bomb booster who took over from Oppenheimer. When we dig our way through the contradictory histories of this era, we still have to wonder what the truth was: was Harry Truman as thoughtlessly inhumane as he appears? There seem to be two parallel truths about the subject in today's split America -- the military version and the Atomic Cafe version. I certainly don't know which is more accurate, as I can only read the same things everyone else can read.

Fat Man and Little Boy doesn't have enough of a point of view to get us excited, incensed or eager to learn more. Oliver Stone may be a revisionist pain in the neck, but he at least inspired some good arguments.

There's a lot of good acting here. Newman's crusty, God-fearing general is a moral fellow for whom national and personal victory are inseparable. Dwight Schultz's Oppenheimer never comes into focus as a full personality, perhaps because the real Oppenheimer was too complex and guarded. He struts like an academic playboy and seethes with moral indignation, but as played it just looks like he wants to make his bomb, blow something up and go home. The ending with Oppenheimer receiving accolades for the successful test comes off as the wrong note for a guy who quoted apocalyptic Indian poetry during the blast. Instead we see The Sorcerers Apprentice in concert (gee, are these guys working for the Devil?) and hear the Nutcracker Suite during the countdown. Are deez classikal elusions?

I was amused by Oppenheimer's face distorting as the bomb went off, an effect clearly achieved by blasting compressed air into his face while a hellish light reflects in his goggles. And this before the shock wave hits. The detonation is similarly stylized, with a gaudy special effects explosion. Strangely, it's less impressive than a scratchy stock shot of the real thing would have been.

Paramount's DVD of Fat Man and Little Boy is a fine enhanced transfer that shows off Vilmos Zsigmond's Panavision images. The disc has no extras, which in this case is a shame -- if ever a feature needed a complimentary docu about the real-life events, this is the one. 1

The box cover artwork skips the two hanging bomb prototypes (Fat Man and Little Boy) that were used on posters and given graphic emphasis throughout the film. This is artistic license gone nuts, as the movie makes it look as though the bombs' final shapes were determined before the scientists knew exactly how they were going to function. All the explanations for why the bombs were dropped (when the Japanese were suing for surrender) pale before the simple evidence of the two prototypes -- besides dramatically showing the world who possessed the ultimate big stick, the Army most likely wanted to compare the killing results of two different bomb mechanisms.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Fat Man and Little Boy rates:

Movie: Good -

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: none

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: May 2, 2004

Footnote:

1. A good comparison is the DVD disc of Pearl Harbor with its fine docus that contradict every last historical fact, situation, assumption, and stupid notion in that ridiculous and insulting film.

Return

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © DVDTalk.com All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |