| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Savant Guest Essay: Working with Cronenberg on Crimes of the Future

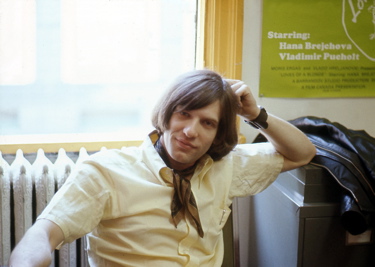

Note from Glenn Erickson: A few months ago, perhaps after I posted a review of the Cronenberg movie Videodrome, Jon Lidolt wrote me to say that he had worked on one of the director's first films in Canada. I was curious to find out what the experience was like and encouraged him to give an article a shot. And here it is! It was the late 60s. Very interesting times for a film nut living in Toronto. Rep houses were flourishing, Kubrick's 2001 was enjoying one of its longest runs in the world at the local Cinerama theatre, and watching a movie on a panoramic theatre screen was still a magical experience that couldn't be duplicated on a 21" TV set.  Jon Lidolt (on right) in Crimes of the Future In the mid-60s I was the art director for a medium size theatre chain called 20th Century Theatres. I spent my days preparing newspaper and magazine ads for movies showing in the city - mostly Hollywood fare but also foreign films that played at Toronto's two main art houses, the Towne and the International. I was vaguely aware that a small home grown feature film industry was in its embryonic stages but the articles I'd read in the papers about it didn't really mean much to me. During this period I'd set up a small screening room in the basement of the house I was living in complete with wide-screen projection facilities, curtains for the screen and old movie posters on the walls. To actually see a Hollywood movie projected onto a 9 ft. wide screen in a friend's home was a big deal back then, and most people considered an invitation to one of my film evenings a real treat. Instead of renting, I paid a co-worker a small fee to "borrow" 16mm prints of recent features for me. One evening a friend of mine came over to watch a movie and showed up with an acquaintance who ran a small film distribution company called Filmcanada Presentations. After the movie and a big gab session about films and questions about what I did for a living - he offered me a job with his company. I was intrigued but not really sure what to do. I'd read about Filmcanada and had recently seen La Guerre est Finie at Cinecity, their new 350 seat theatre. I remember asking one of the bookers at work what he knew about Filmcanada and was surprised by the comment. He told me the place was run by queers and hippies and advised me to stay where I was. But I'd already met some of the Filmcan employees and they had an excitement about movies that was lacking at 20th. I decided to make the leap. In addition to the 35mm titles we handled, our catalogue contained a large number of so-called experimental 16mm shorts and feature length items. The filmmakers on this list included such names as Stan Brakhage, Maya Derren, Kenneth Anger, Andy Warhol and someone I'd never heard of called David Cronenberg. I got to know David during his frequent visits to our office to check whether or not the 16mm print of his film Stereo had received any bookings, bum smokes and just generally hang out. He was soft spoken, well educated and interesting to talk to - I enjoyed David's company and looked forward to his visits.  David Cronenberg visits the Filmcanada offices, 1968 David was aware that I had only seen snippets of his film Stereo badly projected in 16mm and invited me to attend a showing of a 35mm print at a lab called Filmhouse (since morphed into Deluxe). I was impressed by those crisp B&W images on the big screen and realized that David had a unique perspective on the world around him. That, and the fact that he was able to make a 35mm film for around $12,000 amazed me. There was also something about the picture that reminded me of Stanley Kubrick's work, but at the time I couldn't figure out what it was. I mentioned this to two or three other people and they just rolled their eyes. That same year, I was fortunate enough to have met Lillian Gish at the Canadian launch of her book The Movies, Mr. Griffith and Me which I bought and read. I was intrigued by the relative simplicity of silent filmmaking, the freedom to experiment, the fun they must have had and even the hard work that went into these pioneering efforts. I especially noted how flexible they were in dealing with problems. According to Miss Gish, if the editor needed an extra closeup to cut into a scene, she simply took a cameraman out of doors to photograph her in front of a neutral background. There was no need for a huge crew to tag along. Little did I know that I too would soon have the pleasure of working on, what was essentially, a silent movie. One morning, not long after meeting Gish, David told me that he'd received another grant from the Canada Council for the Arts and had already started working on his 2nd movie. The new project, called Crimes of the Future, had already begun filming in B&W when he realized that, with care and a shooting ratio of less than 2:1, he could afford to photograph it in 35mm color. He scrapped the little he'd already shot and started over. This left David with just enough money for camera rental, film stock, lab costs and other incidentals. With the added cost of shooting in color, there was nothing left in the budget for actors. Not a problem for a Cronenberg film - David just recruited friends. When he approached me I couldn't resist the offer. It sounded like great fun. 1 A few days before filming started, David helped me choose the clothes I wore in the picture by rummaging through my closets - that was it. Another day, he came over and we recorded some noises that he'd written out for me to say. I'm not even sure where they are in the finished film, they just blend in with other sounds that he cut into the track. It was all very casual, just a friend dropping in to make a movie. I was originally scheduled to appear in one brief scene, but David liked what he saw and my part was extended. We shot the section of the film that I appear in at Massey College which is part of the University of Toronto. The Master of Massey at that time was well known Canadian writer Robertson Davies who mentioned this incident in one his novels. Whenever we all had time to get together and the weather cooperated, David and his production assistant Stephen Nosko would pick me up in his Volkswagen, along with the camera gear and props. We'd then drive to the location and set up. You know, I have a sneaky suspicion that no one ever obtained permission for us to shoot at Massey College, but then no one ever questioned us about it either. Even so, David never seemed rushed or worried and always gave directions in such a calm, reassuring manner that it gave me the confidence to try almost anything. I heard that he still communicates with actors the same way today. I knew very little about the project while we were working on it - I never did see a script. Although, I did occasionally catch David glancing at some notes scrawled on a crumpled sheet of paper. Come to think of it, a script would have been superfluous since there was no dialogue to memorize. There just wasn't enough money in the budget to shoot synch sound. The only words we hear in the entire movie are those of narrator Adrian Tripod. David shot most of the movie hand-held with an Arriflex which he rented from a small, family-run outfit. Their equipment was old and not well maintained - but it was affordable. There were no markings in the viewfinder to show the 1.85 composition area, important action was simply kept away from the edges and I never did see a tripod on the set. It was easier and less cumbersome to just sit the camera on a box. And for tracking shots, a wheelchair worked wonders. When we shot in dark interiors David just replaced the regular light bulbs in the room with photofloods. When he was almost through with the editing David approached me to design the titles. Not an unusual request since I was already doing Filmcanada's artwork and could squeeze this into my regular routine. It was also a great way to ensure that I would get second billing on the show. Working with Cronenberg on this project was one of the more pleasurable experiences of my life which is why my memory of these events is still relatively fresh. But the colors on the latest DVD release have lost some of their luster - is it simply a poor transfer or are the images slowly fading into the past? Footnote:

1. Jon Lidolt provides this synopsis of Crimes of the Future:

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |