| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

Classic Sci-Fi Ultimate Collection

|

|

Universal Tarantula, The Mole People, The Incredible Shrinking Man, The Monolith Monsters, Monster on the Campus B&W Street Date September 19, 2006 29.99 the set Not Available separately Reviewed by Glenn Erickson |

Universal's Classic Sci-Fi Ultimate Collection has sneaked up on everyone except genre fans, as it's a Best Buy Exclusive offering, for better or worse. The good news is that Universal's best science fiction film ever is finally on video in a correct presentation. The four other titles are icing on the cake.

The set gives the viewer a good look at the downgrade progression of Universal's Sci-Fi's over just a three-year period. 1953 -1955 brought us in quick succession the imaginative It Came from Outer Space, The Creature from the Black Lagoon and This Island Earth, but from then on it was sequels for the Gill Man and imitations of earlier hits. Specialist producer William Alland eventually jumped ship to Paramount. Sci-Fi specialist Jack Arnold wanted out but came back when he saw a script that transcended the limitations of movies with men in rubber makeup.

A rather cheap house style carries through most of the cycle and the acting roster clogs up with rejects from television series, but the fans love these pictures. Universal's poster art from any of these titles is highly collectible. The studio released two fat boxed sets of Sci-Fi Laserdiscs just as that format was being phased out; I remember the price was upwards of $100. This first Ultimate edition (I hope there will be a second) is quite a treasure.

Tarantula

1955 / 80 min. / 1:33 flat full frame

Starring John Agar, Mara Corday, Leo G. Carroll, Nestor Paiva

Cinematography George Robinson

Art Direction Alexander Golitzen, Alfred Sweeney

Film Editor William M. Morgan

Special effects supervisor David S. Horsley

Written by Jack Arnold, Robert M. Fresco, Martin Berkeley

Produced by William Alland

Directed by Jack Arnold

The credits point to an original story (itself supposedly adapted from a TV show), but William Alland lifted the 'big bug' thrills of Warners' giant hit Them! and placed them in a lower budget version of the desert town from It Came from Outer Space, thus launching a hundred leery film-school treatises extolling the Arnoldian Desert Motif. Tarantula isn't half the movie that Them! is, yet it works up its own broth of monster thrills and strange poetic effects. While the human characters exchange small talk, a colossal black arachnid stalks the wide open spaces of the surrounding desert. As big as a mobile mountain, it nevertheless escapes detection while snacking on various peripheral characters in approved monster-on-the-loose fashion.

Tarantula follows the can't-miss formula for monster entertainment: Make sure your monster is bigger than last year's. Led by optical whiz David S. Horsley, the Universal effects department puts a lot of effort into forty or so monster shots showing the giant spider striding down highways, knocking over power lines and sneaking up on unlucky motorists. As with the previous year's giant ants, the outsized crawling bug is accompanied by a loud signature noise, like sizzling bacon put through some kind of E.Q. filter. Unlike the ants, the only practical full-scale part of the spider we see is one hairy fang that smashes through a roof.

Gigantism in movies is hard to pull off. The design geniuses behind pictures like Metropolis and King Kong knew how to cheat the scale of our perceptions to make things LOOK REALLY BIG, a skill unknown to the makers of pictures like Beginning of the End and The Giant Gila Monster. In Tarantula the Universal optical department succeeds most of the time. The optical shots were done by shooting various spiders high-speed (to get the slow motion) and in deep-focus. White plaster miniature landscapes were shaped to follow the contours of the real desert in the live-action footage. When carefully matted into the picture the spider conforms to the curves of hills and rocks, and even throws a shadow. If one is in the correct frame of mind, the sight of the spider stepping over an outcropping two or three miles away is unnerving. He makes a wonderfully subtle entrance creeping up behind a pair of friendly prospectors, with one telltale leg silently peeking over the horizon.

There remain perspective issues, as the hairy arachnid has a tendency to appear a mile across in the far background, only to shrink to a hundred feet or so when he reaches the foreground. Since the performing spiders could only be guided with jets of air, Horsley's camera team must have burned up a lot of film to get useable footage, and been grateful whenever an angle matched up well. It looks as though they weren't allowed to finesse the shots, as several show the spider's legs disappearing into mattes that cut across the sky. In several others the spider is rather transparent.

But in some scenes the effect is stunning. One pre-dawn moment places Universal's ubiquitous Southern mansion-style house on the right side of the screen, with a real desert landscape dominating the left. Way in the distance is the spider, a moving part of the landscape, coming this-a-way. It's an "Arizona Highways" calendar moment gone surreal. The spider seems to be crawling into our reality from another dimension. He's a horrifying menace, but still so far away that it's much too soon to panic. I have nightmares like this.

In his best entrance, the spider reveals itself to most of the cast as they stand by their cars on stretch of desert road. It charges up over the crest of a hill and then freezes, as if holding still to evaluate its new dining opportunities. Then it begins its machine-like crawl again, accompanied by Henry Mancini's recycled menace music from This Island Earth. 1

Lovely Mara Corday has the task of looking concerned while pretending to be a top research assistant in designer clothes. It's neither her fault nor John Agar's that the script keeps them behind the story curve, always asking questions when the audience already knows the answers. Agar's scripted reveries about the desert may be based on Richard Carlson's speeches from It Came from Outer Space, but he hasn't the chops to deliver them. The heavy-drinking actor is most noted (probably unfairly) for slurring a few line deliveries. Leo G. Carroll does well with his sad tales of mix-ups in the lab, although we never understand exactly why these scientists would consider taking a drug that makes bunnies and hamsters into 'sizeable beasts.' Haven't they seen King Size Canary, the Tex Avery cartoon? Speaking of which, Carroll's elaborate, Quasimodo-eyed makeup makes him look even more like Avery's Droopy Dog character.

Tarantula collapses into hilarity at least once, when the giant spider (partially in its poorly-matched puppet version, the one seen on the poster) imitates King Kong by peeking into Mara Corday's dressing room through a convenient giant-size window. She walks back and forth (and even looks in a mirror) but never notices a fifteen-foot monster eyball salivating only a few feet away. When the spider subsequently climbs on top of the house and proceeds to batter it to pieces, it really looks as if it's, uh, aroused. The filmmakers had to be aware of this; it must have been screamingly funny in 1955 drive-ins.

Clint Eastwood (or at least his voice and eyes) appears as the pilot guiding the missile strike that turns the spider into a big Napalm fireball. Tarantula has always been a guilty favorite of giant monster fans, and fits in there right behind the top three or four Sci-Fi offerings of the 1950s. 2

Tarantula is paired with The Mole People on the first disc in the collection. The non-enhanced transfer crops perfectly on a 16:9 television, removing large areas of compositionally dead space above and below the action. I wish Universal had seen fit to go to the extra trouble, but the fact is that the show plays well, even flat. The 1996 laserdisc was rather dark, a problem that seems to have been corrected with this encoding. I notice the difference, and the new transfer looks correct. The only extra is a dupey trailer.

The Mole People

1956 / 77 min. / 1:33 flat full frame

Starring John Agar, Cynthia Patrick, Hugh Beaumont, Alan Napier, Nestor Paiva

Cinematography Ellis W. Carter

Art Direction Alexander Golitzen, Robert E. Smith

Film Editor Irving Birnbaum

Mole People masks Jack Kevan

Written by Laszlo Gorog

Produced by William Alland

Directed by Virgil Vogel

This lackluster "lost civilization" story, a combo of She and The Man Who Would be King, makes the mistake of tackling a big-budget idea with almost no money and an inadequate script; it consequently has little vitality and cannot even work up the excitement of an old Republic serial. We know that something's too tame when the most sparkling personality in the cast is John Agar's dullard archeologist. Everything about the film is underdeveloped. Even the enslaved Mole People come off as odd substitutes for the black slaves seen in other escapist thrillers about ancient worlds.

The best words to describe The Mole People are "rushed" and "sloppy." Not much of anything makes a strong impression. Grainy and scratched stock shots mar the opening reels, with our scientists walking through cheap and tiny mountain sets, and pausing before rear-projected stills featuring large, frozen hairs. An okay descent into a cave is followed by a tour of the underground world of Sumeria ... which amounts to a lot of pitch-black tunnels and three or four matte angles that look like rough sketches for concept approval. The underground civilization is limited to the requisite throne room and a couple of archways.

One of the scientists remarks that the Biblical flood has been proven to be a real historical event, but the existence of a hidden city of Sumer is attributed to the Babylonian epic of Galgamesh, an almost carbon copy of the Christian story of Noah and the ark. Expert Dr. Bentley reads the ancient tablet as if it was a recipe for apple pie. When they meet the Sumerians, he's able to converse with them in their own ancient tongue, which is completely absurd.

The story's She-like gimmick has the Sumerians sacrificing people to the Fire of Ishtar, which turns out to be ordinary sunlight. Sumerians forced into the sunlight are instantly scorched, but when the explorers are "executed," they are of course unharmed. The Pit of Ishtar is at the bottom of a vertical well apparently hundreds of feet into the earth, which means that for the sunlight to be shining straight down on the bottom, the blazing Fire of Ishtar effect would only work for a few minutes on two or three days out of the year!

We only mention all this because there's little or nothing else to grab our interest in the movie. Alan Napier's professional turn as a villainous priest isn't all that exciting, and the movie makes its Mole Men into very un-menacing brutes. They wallow in pits, sink and emerge from the dirt, and not much else. After the expensive tailored full body rubber suits for The Creature From the Black Lagoon Universal cut costs by putting pants on the Metaluna Mutant from This Island Earth. For both this film and The Creature Walks Among Us the monsters basically wear one-size-fits-all masks and gloves, with gunny-sack tunics and pants to cover everything else. That allows scenes with a dozen or so Mole Men to stomp around all at the same time.

The Mole Men have pebbly skin (no fur) and odd insectile gashes instead of mouths. A completely abortive theme has our heroes standing up for Mole-ian Civil Rights, keeping them from being whipped, etc. There's no indication of any gratitude on the part of the monsters, even though they politely return Cynthia Patrick's underwritten Adad character in one piece. If Laszlo Gorog's screenplay originally included more texture, detail or character complication, it was eliminated by a short shooting schedule and a lack of funds. At the end we're given barely enough shots of the Mole Men attacking their Sumerian masters to flesh out the trailer. Director Virgil Vogel must have impressed the Universal brass with his economical shooting style: Lots of economy, little style.

The finished film is unnecessarily downbeat. The Sumerian tablets are smashed and three of the five climbers are killed, with only Nestor Paiva's Professor LaFarge shown much sympathy. His body ends up proving that the explorers aren't gods, like the bleeding bite that ruins things for Sean Connery in The Man Who Would be King. This story has a lot of bad news, as can be judged by Hugh Beaumont's continual look of bored dissatisfaction. He looks ready for the career safety of Leave it to Beaver. (spoiler) Why the insistence on a bleak fadeout, with Adad killed by a freak rock fall? We don't know enough about her to be moved. The movie ends on a pointlessly somber note.

The beginning is something else. In a prologue added to bring the feature to minimum length (and routinely dropped from old TV showings) USC English professor Dr. Frank C. Baxter gives a hilariously nonsensical speech on hollow earth theories. Baxter's's 'expressive' gestures to enliven his oratory have to be seen to be believed; his hands behave as if they have a mind of their own. I really wouldn't be surprised if David Byrne found inspiration here -- Same As It Ever Was!

Universal's DVD of The Mole People is also transferred flat. The acres of empty screen space for us to contemplate makes it seem even more boring. The image mattes off to a more acceptable 1:77 on a 16:9 monitor. Some of the stock shots are very grainy, but otherwise the transfer is excellent. The trailer uses every exciting shot in the movie.

The Incredible Shrinking Man

1957 / 81 min. / 1:78 anamorphic 16:9

Starring Grant Williams, Randy Stuart, April Kent, Paul Langton, Raymond Bailey, William Schallert

Cinematography Ellis W. Carter, Clifford Stine

Art Direction Robert Clatworthy, Alexander Golitzen

Film Editor Albrecht Joseph

Special Effects Charles Baker, Everett H. Broussard, Roswell A. Hoffmann, Fred Knoth, Tom McCrory

Written by Richard Matheson from his novel The Shrinking Man

Produced by Albert Zugsmith

Directed by Jack Arnold

When deprived of star names and big budgets, studio genre work often tended to be formulaic and predictable. Like Columbia's lesser crime films, Universal's 'monster' output probably suffered significant studio indifference. With the budget, script and cast locked, there wasn't much room for improvement. Blah dailies might be tolerated but God save the director who dared deviate from the day's approved call sheet.

The Incredible Shrinking Man is a happy exception. Producer Albert Zugsmith had just hit solid with Douglas Sirk's star-studded Written on the Wind and was making more Universal pictures with bigger names like Jeff Chandler. He obtained Richard Matheson's creepy novel The Shrinking Man and decided it would be perfect for an offbeat Science Fiction tale. Either somebody had imagination or the thing was green-lit during vacation time, because Zugsmith's The Incredible Shrinking Man outdoes all of William Alland's Sci-Fi efforts. Kids loved the miniaturization effects, a concept seen mostly in comedy fantasies since the failure of Paramount's Dr. Cyclops back in 1940. Matheson's adult, thoughtful script crystallizes Cold War phobias much as had the previous year's Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Seeing a chance to 'make a good one', Jack Arnold came back and contributed his best job of direction. What might have been a shaggy-dog story with an unsatisfying twist ending became a wondrous delight. The Incredible Shrinking Man is Science Fiction poetry and the most profound Sci-Fi film of the fifties.

Universal's presentation finally allows this marvel to be seen in its proper aspect ratio.

The older Gothic tradition conceives of its horrors in terms of suffering and death, and the loss of one's soul to bestiality or the Devil. The new Cold War fears of the 1950s unleashed an existential crisis into the public psyche. The most famous 'intelligent' 50s Sci-Fi thriller Invasion of the Body Snatchers is about depersonalization and the loss of identity. It made audiences uneasy with the sneaking suspicion that things weren't what they seem to be, that the world we see might be some kind of vast political conspiracy.

The Incredible Shrinking Man exploits a different but complimentary fear of the new post-atomic world, a world in which common values, presumed facts and assumed conventions might be completely transformed. Scott Carey must come to grips with an imminent and implacable fate that may not only destroy his life but render it meaningless as well.

There is a classic kind of character that discovers his true nature by losing or casting off artificial and material things; many philosophies including the Christian faith tell us that this is a path to spiritual grace. Carey goes through a similar process except that his is an involuntary ordeal. As he shrinks bit by bit toward that inescapable zero of personal oblivion, Carey loses everything by which he defines himself. First his clothes don't fit. Then his wedding ring falls off. The doctors concentrate on Scott's biological problem but nobody knows how to deal with his mental state. Scott's wife has to mother him like a child. Man becomes toy, husband a helpless baby.

Matheson's original novella emphasized Carey's sexual trauma as he realizes that he's no longer going to be intimate with his wife, that she undoubtedly will have to find someone else. His resentment grows with the forced isolation, and he knows that his personality is changing along with his situation. He can't help it.

Normally a 1957 movie would have to ignore this sex angle but The Incredible Shrinking Man carefully keeps it in the forefront. Tiny Scott shouts at his wife and demands that she come straight home from the store. Nothing she does is good enough. He's trying too hard to hang on to his old dominant attitude, the one that could 'order' Louise to bring him a beer as part of a conventionally equitable relationship. Scott at first looks like a little kid in his jeans and tennis shoes, sitting on a chair with his feet barely reaching the end of the cushion. Having a sex drive with such a small body must seem like a horrible joke, a castration nightmare out of Jim Thompson's The Nothing Man.

At one point Carey wanders out to the carnival and is revulsed by the circus freaks. But he meets a young midget (April Kent) and begs for her company, seeking the security any kind of 'normalcy' can give him. A good husband becomes both abusive and unfaithful, but Carey has no psychological choice -- he's desperate to keep his self-definition intact, to remain a man. Even the company of midgets does not last, when he continues to shrink smaller than they. Carey doesn't know it yet, but his only certainty is eternal change -- and utter isolation in the knowledge that his fate must ultimately be faced alone. Already withdrawn from his normal suburban existence, Scott is drifting into neurosis when events plunge him into a miniature Robinson Crusoe world.

The horrors in Scott Carey's cellar express a chaos beyond simple disproportion; only in a paranoid fantasy could one envision the ordinary, mundane environment of one's own basement turned as hostile as this. The Incredible Shrinking Man in this way resembles Alice Through the Looking Glass in its surreal re-ordering of existing reality. Alice's dream terrors came from nursery rhymes; Carey's emerge from the pages of pulp fantasy in the form of a nastily tangible spider. Scott rallies his strength by flexing an instinct built into the human race -- the Territorial Imperative. The big unknowns can be staved off if one busies one's self with the immediate problems of survival. How else has the human race survived so long?

To battle the horrible spider menace Carey must summon resources he never knew he had. Victory once again forces him to consider the bleak future, but now he realizes that he's no longer afraid. That's when The Incredible Shrinking Man pulls out its ace, an ethereal conclusion that reportedly was not written by Matheson and was added against his wishes. Carey has survived, he's passed the test. Some philosophies seek truth by finding one's true self. Others teach that truth can only be found by casting off one's ego and joining a natural order larger than the Self and perhaps incomprehensible to the material-bound consciousness. Only a fraction of an inch tall, Scott is able to walk through a barrier that previously blocked him. Nothing in his world will ever be the same -- unless other 'incredible' men follow his trail into the unknown. But he looks up at the sky and experiences a revelation: The stars are so distant, that they haven't changed at all.

I've been at screenings of this film in which one could feel an "ah" rise from the audience when the camera pulls back on Carey's words "And I felt myself melting ..." Many people, especially kids that might never have considered the possibility of transcendence, can feel the pull on some part of their minds. As Scott continues with his final speech, The Incredible Shrinking Man achieves what might be the most profound "Sense of Wonder" scene in Science Fiction. Scott's concluding revelation, sometimes interpreted as an ethereal surrender to fate or even an expression of the death experience, is really a triumph over complacent existence. With the simple defiant words "I Still Exist", Robert Scott Carey becomes a hero of the Atomic Age. 3

When I first wrote about The Incredible Shrinking Man in 1981 it seemed to me that Scott Carey's battle with the spider was one of the best special effects sequences ever made. It's still good but modern fans will have no trouble picking apart the perspective tricks, split screens and traveling mattes. One wishes all the original optical elements existed so the shots could be re-composited more perfectly -- shadows for the tiny Scott, etc. But the narrative imagination in Matheson's script makes 'perfect' effects unnecessary. The Shrinking Man works because of the little observations, like Scott's wedding ring falling off just as he and Louise are affirming their unbreakable union. It hits exactly the right note.

Part of the brilliance, and the aspect that is hard to believe ever made it through the script stage, is the basic bad-news ending. In practically every other show of this kind (even today), the doctors find the antidote and the story fades out with the situation solved. Think of Outbreak where a simple injection stops a deadly virus and magically repairs organ and tissue damage! Once Scott falls into the cellar and becomes part of the alternate miniature underworld, he's never heard from again. His wife thinks she's a widow and never learns the truth. At the ¾ mark the housewife leaves the house in a car and never comes back. Never. The Incredible Shrinking Man deals with the infinite and finality. 4

The source of Scott's trouble is at first a mystery, then a theory and finally becomes irrelevant. The film's first potent image is a man alone facing an approaching 'mystery cloud'. There's no escaping the cloud; all one can do is watch it overtake the boat. Radioactivity must have accounted for 20 or 25 'atomic movie monsters' in the years around this film but The Incredible Shrinking Man makes it a footnote, prophetically combined with ordinary pesticide. The fantastic nature of the story is not harmed by the utter absurdity of the film's supposed science -- for Scott to shrink so perfectly his cells would have to shrink proportionately, not just diminish. And how do hard bones get smaller -- once formed, they're largely inert. Scott's plight is better off left as a philosophical enigma.

Universal presents its DVD of The Incredible Shrinking Man in a beautiful enhanced widescreen 1:78. Savant hasn't seen it this way since 1973 at the Los Angeles County Museum with Richard Matheson in attendance. Even a recent showing at the American Cinematheque used a flat, pan-scanned print. The full restored widescreen reveals visual harmonies lacking in all the older 1:33 video transfers. Although shot with flat spherical lenses, The Shrinking Man was hard-matted in the camera (and/or the optical printer) to eliminate the need to do effects for areas of the frame not intended to be projected. The earlier transfers took a 1:33 piece out of the middle of the already-matted frame (just as had Invasion of the Body Snatchers for television), resulting in a fuzzy image with important East-West information missing.

The compositional improvement is evident all through the picture. Scott and Louise no longer talk to each other from extremes of the frame and the full perspective angle down the cellar shelf to the spider's web now looks like quite a hike. By now effects cameraman Clifford Stine had gained plenty of experience, and with Arnold's guidance pulls off a terrific series of effects angles and moving shots. 5

Clear sound augments the sharp picture; Ray Anthony's trumpet calls over the main titles while the little Scott Carey figure shrinks, and shrinks .... We hear a smattering of Written on the Wind-ish soap opera music on Scott's radio, making his shut-in home life seem even more drab. As an extra, we're offered the Saul Bass-like teaser trailer with Orson Welles giving Shrinking Man a very classy introduction -- it doesn't even use scenes from the movie. With Welles reading the narration, we'll believe anything can happen.

The Monolith Monsters

1957 / 77 min. / 1:33 flat full frame

Starring Lola Albright, Grant Williams, Les Tremayne, Trevor Bardette

Cinematography Ellis W. Carter

Art Direction Alexander Golitzen, Robert E. Smith

Film Editor Patrick McCormack

Special Photographic Effects Clifford Stine

Written by Jack Arnold, Robert M. Fresco, Norman Jolley

Produced by Howard Christie

Directed by John Sherwood

Capably made and introducing perhaps the oddest of 'space invaders' ever to menace the Earth, The Monolith Monsters is eventually too Earthbound to rise out of the B-picture ghetto. Fine work from Shrinking Man Grant Williams and Lola Albright holds the narrative together but a formulaic script leaves them little room to breathe. Director John Sherwood (The Creature Walks Among Us) keeps up the suspense, making Monolith into a minor overachiever.

The Monolith Monsters could almost be a template for the generic 50's monster threat movie. The menace (revived dinosaur/beast from space/mutated life form/giant insect) first appears in an odd form that leaves baffling clues and various victims dead in mysterious ways. With the aid of a loyal and patient girlfriend type, a young scientist (or scientist wannabe) eventually discovers the real truth of the menace just as it is about to leap to a new level of terror and threaten the whole world. The hero struggles to get official cooperation (martial law/military intervention) and the radical resources (radioactive gun/CO2 fire extinguishers) needed to stem the menace. After some visually exciting mass destruction, quick thinking and plain good luck enable the hero to put things right. With the menace stopped, the fadeout gives us the time to ponder the next step. Are similar threats on the way? Will we be ready?

This worth of a film based on this formula depends on the specifics, and on most counts The Monolith Monsters rates a 'not bad at all.' Even if they have no personality, the crystal monsters are certainly unique, forming impressive towers of rocks that crash down only to sprout up anew, like giant marching crabgrass. This idea had to be inspired by someone observing their kid's High School crystal science project!

The names on the script suggest that the story structure was cloned outright from the earlier Tarantula, with the action taking place in a similar desert mining community. The leads are more interesting than in the earlier film, with the likeable Williams making a concerned hero, while the near-cult figure Lola Albright (A Cold Wind in August, Lord Love a Duck) has little opportunity to exercise her talents. In the final scene Lola is directed to jump for joy with the rest of the cast, and we can see her straining to comply.

The Monolith Monsters starts with meteor stock footage and alternate takes from It Came from Outer Space but after that it's all new material. The piles of rock and 'stiffening' victims make for a good puzzle to ponder, and the scientists are just smart enough to use simple logic to produce an antidote. The only frustration comes when Miller, a visiting professor (Trevor Bardette) and the friendly newspaperman (Les Tremayne, even more charming than usual) try every exotic chemical they can think of to see what triggers the extraterrestrial element to expand -- except getting it wet!

The film also generates a feeling of nostalgia for its unrealistic 50s attitude to problem solving. The big city doctor goes right ahead and administers his experimental antidote to the young girl without a thought for the usual concerns of authorization from next of kin, waivers, etc.. Today it's entirely probable that red tape delays would hasten her conversion into a new citizen of the Petrified Forest. On the say-so of just the local geologist and his scientist sidekick, the highway patrolmen back up whatever wild plans are proposed, including blowing up a giant dam critical to the region's economy. So what if the governor can't be reached in time for approval? Even the dam personnel help when trucks full of dynamite drive up and the demolition begins! That's what I call going out on a limb.

Clifford Stine's miniature effects photography is outstanding, with two or three flawless master shots of people observing the marching crystals from afar. The black towers crash down on a miniature farm that looks suspiciously identical to the farm model in The War of the Worlds. The only real flub Savant detected is when a buckboard wagon in the farmyard remains unharmed even after being hit by 200 tons of falling rock! One overhead angle of the town square with a desert matted around it reminds us of similar Universal backlot shots in Gremlins and Back to the Future.

William Schallert makes his umpteenth monster show appearance as a chatty weatherman. We barely get a peek at hopeful Troy Donahue but Paul Petersen (The Donna Reed Show) has a fat little bit as a go-getter newsboy.

Universal's The Monolith Monsters looks fine, as it always has. The 1:33 image crops well to 1:78 for all but the main title, which is slightly too tall to fit. The trailer hypes the film's menace, perhaps dissipating curiosity more than encouraging it.

Monster on the Campus

1958 / 77 min. / 1:33 flat full frame

Starring Arthur Franz, Joanna Moore, Judson Pratt, Nancy Walters, Troy Donahue, Phil Harvey

Cinematography Russell Metty

Art Direction Alexander Golitzen

Film Editor Ted J. Kent

Written by David Duncan

Produced by Joseph Gershenson

Directed by Jack Arnold

With this final title we can just start to see the bottom of Universal's monster barrel; fans are already wondering why more attractive fare like The Deadly Mantis or The Land Unknown weren't included instead. This collection may be 'Ultimate' but if we're lucky it will be followed by an 'Ultimate 2' with Mantis, Unknown and more horror-oriented titles like Cult of the Cobra, The Leech Woman and The Thing that Couldn't Die. And don't forget Curucu, Beast of the Amazon which is neither Sci-Fi nor horror but always gets lumped into the fantasy category just the same.

Monster on the Campus is fairly trivial drive-in fare with one or two "Boo!" moments and a lot of talk by characters that can't seem to figure out what we can spot from the very beginning. This one crosses Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde with the central idea from an E.A. Dupont United Artists quickie from five years earlier, The Neanderthal Man. It shares with the earlier picture a caveman-type bogeyman created with the use of a static, fake-looking rubber monster mask. When not belaboring the obvious, the David Duncan screenplay does have a bit of fun with its characterizations.

I'm going to go out on a limb and venture that the idea for Monster on the Campus came when the creative screenwriter David Duncan (The Time Machine) visited the Los Angeles Natural History Museum and saw its Coelacanth exhibit. The prehistoric fish is real -- paleontologists were startled to find one alive, when they previously had only known it in fossil form. The fish is still there in Exposition Park, pickled and badly in need of a new display case ... the glass is getting pretty cloudy. No, the case didn't leak; Savant's simian characteristics must be from some other source.

It's interesting that Duncan should work with an evolutionary theme similar to the one in the H.G. Wells classic he was soon to adapt. Arthur Franz' dopey Professor Blake is obsessed with evolution and reminds everyone that, should civilization ever give out, we're all just one generation away from prehistoric savagery. Sure enough, he soon discovers that the brutish killer terrorizing the campus is himself. This occurs in a rather funny scene where he puts it all together, staring at the cut from the ancient fish's teeth, and then sniffing the pipe into which some fish blood dripped before he became the monster a second time. Blake is a really sloppy scientist. He leaves a rotting fish out in the open, sticks his hand down its throat, etc. His idea of proper curatorship is to give the Coelacanth a quick shove into a refrigerated room and slam the door.

Monster on the Campus has a wonderful example of what Savant calls the Metaluna forehead effect. The wolf dog suddenly has fangs as long as a saber-tooth tiger's. They should be spotted from across the room, but Blake has to point them out for anyone to notice. The script and the visuals don't agree.

This must have been a major backslide project for director Jack Arnold, who would soon be moving up to better assignments like The Mouse that Roared. More likely than not audiences thought it was meant for laughs, as by 1958 the majority of monster films were to some degree self-conscious self-parodies. Franz nonchalantly plays with a big plastic dragonfly that wouldn't fool a child. Led by the talented Joanna Moore (later known as Joanna Cook Moore), the actors take it all seriously, with the result that they look like dolts for not figuring out the infantile plot.

Arnold's direction has the smooth but unstylish feel of TV work, with a couple of unusually violent exceptions. College nurse Helen Westcott is found hanging in a tree and unlucky forest ranger Richard Cutting receives a hatchet blow to the face. Despite these thrills (?) we find our minds wandering. Janitor Hank Patterson also played janitors in the same year's Attack of the Puppet People and Earth vs. The Spider.. He could have done TV ads for floor wax: "Hi! I'm not a real janitor but I play one in many movies ..."

Feminist critics desperate for material can find fertile ground in Monster on the Campus, as Dr. Blake's pointed remarks start with his first line: "Ah, the human female in the perfect state -- helpless and silent." It's interesting that both women in the story are dishonest manhunters. Blake's first victim attempts to poach him from his fiancée Madeline. Madeline claims that she believes in his innocence, but tries to cover for him in the police investigation. She also immediately checks the registration of a car parked in front of his house, indicating that she's willing to believe he's cheating on her, too. The film might have been more interesting if the two women regressed into cavegirls and went at each other with clubs.

Like I say, Monster on the Campus is the kind of movie that makes one stretch for interesting comment.

Universal's DVD of Monster on the Campus is another excellent transfer that looks better enlarged and trimmed on a 16:9 television. A forgettable but welcome trailer rounds out the package. Universal put out a press release a couple of weeks prior to the disc street date with the assertion that its 1:33 transfers were correct. This elicited the DVD fan equivalent of an Angry Mob With Torches, as the fan base for these films -- at least the vocal fan base -- doesn't appreciate being fed convenient misinformation. Just the same, Monster on the Campus and the other widescreen pictures still look reasonable when shown full frame.

Universal's Classic Sci-Fi Ultimate Collection comes in a gaudy colored plastic sleeve that reveals more interesting artwork underneath. Mara Corday takes the place of honor, screaming in photos on both the front and back covers. Monster on the Campus has a disc to itself, which seems a waste -- the smart move would have been to give that honor to The Incredible Shrinking Man. Some packages also contain a bonus disc called Battlestar Galactica: The Story So Far.

Someday we hope to see the most deserving of these thrillers, especially The Shrinking Man and This Island Earth, given deluxe treatment with commentaries and featurettes. Scholars like Steve Rubin, Tom Weaver and Robert Skotak have reams of insightful & fascinating research to share.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

|

Tarantula rates:

Movie: Very Good Video: Very Good Sound: Excellent Supplements: Trailer |

The Mole People rates:

Movie: Fair + Video: Very Good Sound: Excellent Supplements: Trailer |

|

The Incredible Shrinking Man rates:

Movie: Excellent Video: Excellent Sound: Excellent Supplements: Trailer |

The Monolith Monsters rates:

Movie: Very Good Video: Very Good Sound: Excellent Supplements: Trailer |

|

Monster on the Campus rates:

Movie: Fair + Video: Very Good Sound: Excellent Supplements: Trailer |

Reviewed: September 22, 2006 |

Footnotes:

1. The 'charge in and freeze' entrance seems to have inspired the third Lord of the Rings Movie when that spider monster (yes, I know it has a name) suddenly appears from a mountainside cave. Cartoonist Gahan Wilson perfectly captured Tarantula's surreal gigantism effect in a Playboy cartoon around 1967. Two guys at a tiny burger shack on the highway stare out at the dark hills far away. One of the hills is really a toad-like monster with two gigantic eyes, and it looks like it's crawling their way. The customer looks up at the shack's neon sign that says "EAT", and says. "Good God - do you think it can READ?"

Return

2. Video prep people have 'fixed' a flaw in Tarantula that I looked forward to on many old TV and 16mm showings. When Agar's convertible slides to a stop in Deemer's driveway, there's a hard cut to a composite shot of Corday running from the crumbling house, with the monster struggling on top. Somebody goofed in the original negative conform, because at the cut point there used to be two frames of a camera slate where the monster inset belongs (it's a complicated optical shot). Just a blip, but it got more obvious with each viewing. The video boys snipped it out for VHS and Laser versions. So where's the fan indignation when we need it! We want our two frames of camera flub back!

3. Another movie from 1957 is about a woman of modest means, set in her ways, not too bright but with a good heart. Cheated and robbed, she loses her house, her possessions and her money, until at the end she's walking along with nothing, a total vagrant. All her material possessions are gone. In the last shot she looks at the camera and smiles. She's still there, she hasn't changed. Some human essence in her cannot be taken away. She breaks the barrier between the filmed story and the audience, and looks right into us. The movie is Federico Fellini's best, The Nights of Cabiria, and it practically parallels The Incredible Shrinking Man.

4. Many acid-rock & "ethereal cereal" lyrics sound faintly ridiculous now, even much of the feel-good mellow vibes of The Moody Blues. Their space-themed album To Our Children's Children's Children obviously riffs on 2001 to revisit older Sci-Fi ideas. The lyric "You've Got to Take the Journey Out and In" seems connected to The Incredible Shrinking Man's idea of infinity, where the impossibly big and the impossibly small meet "like the closing of a gigantic circle." In other words, it's all in your heads, pilgrims. If you want go to the stars, you have to come to terms with the secrets of the atom. If you want to embrace the universe, you must also look deep inside yourself. Pass it this way, please.

5. At that old Museum screening Matheson practically apologized for the movie, telling the audience he hated its altered ending. Much later, he saw it again and changed his mind. At that screening Savant remembers distinctly seeing a "SuperScope" logo on the film. 1958 was a big year for flat movies to be reformatted in SuperScope to yield higher rentals from exhibitors; it's already been established that this was done to the Harryhausen film 20 Million Miles to Earth. Did the SuperScope people do a few test conversions for other studios? Or does Savant suffer from a faulty memory -- from 33 years ago?

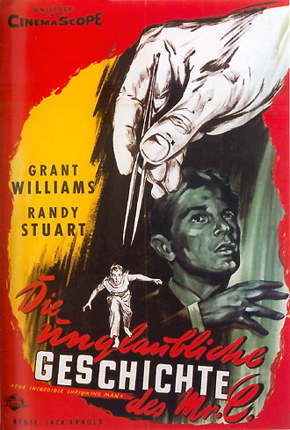

< --- But note this German poster, with the obviously incorrect CinemaScope logo ... was The Incredible Shrinking Man converted to SuperScope for the German market, and they simply got the logo wrong?

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © DVDTalk.com All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |