| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

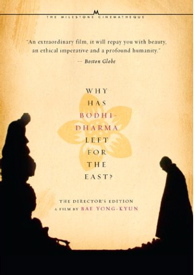

Why has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? |

|

Why has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? Milestone / New Yorker 1989 / B&W / 1:78 anamorphic widescreen /145 135 min. / Dharmaga Tongjoguro Kan Kkadalgun? / Street Date October 16, 2007 / 29.95 Starring Cinematography Bae Yong-kyun Film Editor Bae Yong-kyun Original Music Chin Kyu-yong Written by Bae Yong-kyun Produced by Bae Yong-kyun Directed by Bae Yong-kyun |

The intersection of film critics and Zen practitioners must be a big one because the relatively unknown Why has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? received some of the most glowing reviews of the 1990s. Three of Sight and Sound's critics put it on their lists of the ten best films of all time. Historically speaking, cinematic attempts to dramatize transcendental states have resulted in a great many confused movies. Despite the fact that eastern philosophies teach meditation to discover inner secrets words cannot describe, screenplays on the subject tend to be wordy in the extreme. In the degraded spiritual environment of the movies, time spent contemplating the infinite in Tibetan monasteries is more likely to give one super powers or enhanced martial arts skills. The Tyrone Power version of The Razor's Edge, for instance, shows our hero returning from the mountaintops with superior powers of mental concentration, like Mandrake the Magician.

Director Bae Yong-kyun performed all of the film's creative functions except for composing its musical score, and it's safe to say that he's avoided most of the pitfalls of commercial filmmaking. Why has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? moves slowly and is very long, but it does have a story and characters to follow. Bae Yong-kyun took years to collect his breathtakingly beautiful images, and relies on nature's wonders to communicate his basic ideas. If living in harmony with nature is central to the Buddhist philosophy, the movie is definitely on the right track.

Playing out at a serene pace, Why has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? has two parallel threads, the literal and the unseen. The ideas upon which the master Hyegok has based his life are simple: existence is but a transitory dream and the material world of desires and emotions are irrelevant. Even love does not last. The only meaningful activity in life is meditation, to empty one's mind in search of visions from beyond this existence. Hyegok tells Kibong that since man both comes from and reverts to earth and ashes, we should think of ourselves as people already buried in the ground. Meditation is a way of finding the 'roots of enlightenment' that lead to the greater light above.

The mystery of how exactly to find those roots of enlightenment is not what Why has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? is about. We instead see three men engaged in an essentially earthly struggle. Old Hyegok has found contentment in his quest and appears to have accepted the fact that he cannot break all of his ties to the human race. His adoption of Haejin proves that he needs the same human relationships enjoyed by the decadent world below. Hyegok answers Kibong's questions as best he can, knowing that he made many of the same mistakes. Thinking that he could reach his goal by neglecting his body, Hyegok gave himself a severe frostbite years ago, the effects of which are now dragging him down.

Kibong fears that he's a failure because he hasn't severed his connection to the outside world. He journeys back to the city to beg for coins with which to buy herbal medicines for his master. Before returning he stops to see his blind mother. She asks if it is Kibong at her door. He almost responds but instead leaves without saying a word. Kibong had been miserable and unfulfilled with his mother, but the memories of home impede his spiritual progress.

Little Haejin is a veritable nature boy learning the harsh realities of the real world. A group of playful boys almost drowns him. Lost in the woods, Haejin finds his way home by following Hyegok's cow, which escaped the night before. Most of Haejin's fragmented adventures carry little specific significance, yet we get the feeling that they are related to concepts in Buddhism, or are meant to suggest traditional Buddhist stories. Even the film's title is a tangential reference, being a riddle used by monks to facilitate meditation. To discover the unknowable, one must ponder the unsolvable. The seemingly endless views of forest scenery -- never merely photogenic and edited to imply unseen relationships -- suggest a meditative form. If Bae Yong-kyun's second goal is to create a film that itself encourages meditation, he's certainly succeeded. The images of light on water and rounded stones imply a sense of harmony, of grand design. In this respect the movie functions similarly to Godfrey Reggio's Powaqqatsi, but without the hypnotic Philip Glass musical score.

When Bae Yong-kyun gets down to specifics, he's as literal as any other filmmaker. Haejin maliciously tosses a stone at two birds, injuring one. The bird's distressed mate stands an accusing watch over the little boy for the rest of the film, and is visible perched in the background in more than one shot. When the hurt bird dies, the guilty Haejin hastily disposes of it. He cannot avoid returning to see its body days later. Shocked at the sight of worms, the boy loses his footing and falls into a mountain stream. It's a simple expression of the concept of karma.

(Spoilers) The death and mortification of the bird is visually equated with the passing of old Hyegok, who leaves instructions for Kibong to carry out an exhausting cremation ritual. To fulfill his duty Kibong grinds the remnants of his master's bones into dust. Hyegok never accomplished his breakthrough but he achieved a degree of inner grace, which the film implies is miracle enough. His commitment finished, Kibong gives his master's few possessions to Haejin and leaves the retreat. Although some reviewers see an ambiguity here -- is Kibong going off on his own pilgrimage, or returning to 'the world?' -- I'd have to choose the latter. He's taking with him the cow, a very worldly and material asset.

(More spoilers) Unfortunately, the ending comes off as a bit forced. Now truly abandoned, Haejin doesn't even look at the little package of Hyegok's personal effects, but burns it as if he intuitively knows what to do. Haejin's accusing bird chooses that moment to fly away, freeing the boy from his karmic debt. Is Bae Yong-kyun implying that Haejin, unspoiled by any contact with the mundane world, is the true and natural inheritor of Hyegok's wisdom, and has a great potential to succeed in the meditative life? After 2.5 hours of ambiguous imagery, we're more suspicious than ever of conventional message making.

Milestone and New Yorker's DVD of Why has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? is a real beauty. Bae Yong-kyun's beautiful visuals would wilt in a lesser presentation, but the fine enhanced transfer reproduces the delicate tones of a good theatrical experience. Cut by a reel for its 1993 American release, the film's full length has been restored for the DVD. The audio is in DD 5.1 and DTS.

The disc comes with no extras, which makes Milestone's press kit notes a recommended read, post-viewing. They're Online At this address. At one point in the film Hyegok determines that Haejin has some teeth that need pulling, and calmly talks the child into undergoing the old-fashioned pull-the-thread extraction method. The charming episode seems as if it must correlate to a Buddhist teaching or fable, but Bae Yong-kyun allows it to breathe without imposing a lesson from the outside.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Why has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: none

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: December 11, 2007

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © 1999-2007 DVDTalk.com All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |