| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Frank Sinatra - The Golden Years Collection (Some Came Running, The Man With the Golden Arm, None But the Brave, and More)

In honor of the upcoming tenth anniversary of the death of Frank Sinatra, a whole slew of films starring the Chairman of the Board are making their way to you for the first time on DVD. Warner Bros.' Frank Sinatra: The Golden Years features five titles spanning ten years in the movie-making history of Ol' Blue Eyes. Transfers are near perfect; audio mixes are, well... mixed (only one in 5.1), and a few extras probably make this five-disc boxed set a must-have for the Sinatra completist. Let's look at the individual films.

THE TENDER TRAP

Based on 1954's modest Broadway hit of the same name by Max Shulman (Rally Round the Flag, Boys) and Robert Paul Smith, 1955's The Tender Trap stars Frank Sinatra as Charlie Y. Reader, a successful theatrical agent who lives like a sultan in man-hungry New York City. A steady procession of lovely ladies parade in and out of his apartment, ready and willing to marry him, while providing a steady supply of 1950s wifely services such as cooking and cleaning - in addition to more private companionship - while they wait for Charlie to finally settle down. Into this fantasy world pops childhood friend Joe McCall (David Wayne), a square from the suburbs whose wife has politely asked him to take a "vacation" from her for awhile, until he can come back and "chase her around the house" like he used to when younger. Stunned by the bevy of beauties that Charlie has at his fingertips, Joe is thrown for a real loop when Charlie's steady favorite, cool, ironic cookie Sylvia Crewes (Celeste Holm), proves to be an irresistible object of forbidden longing.

Which won't be forbidden for too long, because Charlie has fallen - quite against his own will - for stage newcomer Julie Gillis (Debbie Reynolds). Getting the chance of a lifetime (starring in a Broadway play for her very first paid job), Julie certainly doesn't show much excitement at the prospect of sudden fame because she has only one thing on her mind - getting married. Setting the date of her parents' anniversary as her last-chance at marriage, Julie won't sign a run-of-the-play contract because it will interfere with her plans, which include exactly how many children she wants, when they'll arrive, what sex they will be, and what school system they'll go to. Charlie, whether in shock at meeting someone so primly organized, or puzzled (and attracted) at a desirable woman who doesn't want him (Julie says she knows instantly if the chemistry is right; i.e.: if the man wants to get married), begins to fall for Julie, who eventually falls for him. But complications arise when Joe declares his love for Sylvia, and Charlie becomes engaged to both women - without their knowing it.

SPOILERS ALERT!

Released during the height of Frank Sinatra's first film "comeback" after he won the Academy Award for 1953's From Here to Eternity, The Tender Trap was just one of six films released during the two year period following that sensational performance. As The Tender Trap's trailer accurately states, no celebrity was more talked about during this period than Sinatra, whose records and films were consistently hitting the number one spots, while his preternaturally turbulent personal life was the subject of almost daily gossip. According to most accounts, The Tender Trap was quite a hit with the public (and for the most part with critics, as well), but seems quite dated today, with genuine laughs few and far between - along with some 1950s cultural howlers that modern audiences (particularly women) might find hilariously old-fashioned.Typical of a certain male-fantasy world depicted in Hollywood comedies of this type, where successful men are besieged by hoards of women looking to ensnare them into marriage, The Tender Trap lets the audience know right away where women and men stand in relation to their...relations, if you will. The opening scene (after the stunning pre-credit sequence - where an almost 3-D Sinatra strolls up to the camera, singing the title track) has Charlie prone on a coach, in his luxurious bachelor apartment, with the luscious Poppy Masters (Lola Albright) feeding him a cigarette. After a sated drag, he gives her the okay to kiss him passionately, with a deliciously real, smirky Sinatra grin on his face and winking come-on that says, "This is a man's world, baby - now let's ring-a-ding-ding." Women in The Tender Trap are servants, essentially (at least at the beginning of the film), meant to keep house and provide unending physical (and, it's implied) sexual comfort for the male, with the level of commitment to the relationship strictly controlled by the man.

Sure, later on, Julie challenges Charlie's commitment phobia, and Charlie comes to realize that his life is pretty empty (particularly when all his past girlfriends dump him), and you start to think that The Tender Trap might be rather forward-thinking in its approach to men and women in 1955 America. But before the final fade-out, the film undercuts this non-conventional outlook by firmly placing the two female characters back in harness - after they've learned their lessons, of course. Sylvia (wonderfully played by the magnetic Holm) makes sure, when she's letting down the misguided, love-sick Joe, that he understands what's waiting for career women who reach a "certain age" (in this film, 33-years-old) who aren't already married: "...married men, drunks, pretty boys looking for someone to support them, lunatics looking for their fifth divorce." As for Julie, despite her displeasure with Charlie's ways, she gets exactly what she wants in the end: a ring on his finger. He's been tamed, and she's now fulfilled. Current critics like to find serious undertones in The Tender Trap, but they always seem to reference Charlie's growing-up - and never the submissive, limited roles that women suffer here (just to put a point on it, the film marries off Sylvia at the end, too, with a perfect English suitor showing up to finally giver her what she craves).

However, all the dated sexual politics aside (after all, the Doris Day comedies from the same period are still delightful), The Tender Trap fails first and foremost because it just isn't all that funny. The premise is silly enough (although you never really believe that grave little Julie believes her own list for an impossibly perfect husband and family life), and the gimmick of having Charlie's boyhood chum, who thinks he's stuck in a lifeless, humdrum marriage (until the film tells him he's not and to get his can back home and be grateful for what he's got), dropped into the middle of Charlie's harem should yield some solid laughs. But the screenplay by pro Julius Epstein (Casablanca, Send Me No Flowers) fails to deliver any memorable gags or truly funny lines, with a draggy pace and actors who seem mismatched to their characters. Sinatra, to his credit, is visibly trying during this period in his career where he was grateful to be working again and where he still truly cared about his film projects. But he's not particularly funny here, while grim little David Wayne (who must have been picked so as not to tower over Sinatra) is positively un-funny as comedic foil to Charlie. As for Debbie Reynolds, she doesn't seem to have much to do here, although when she gets a chance to sing along with Sinatra to the title tune, they are undeniably cute and charming. Too bad they weren't allowed more scenes like this together. And director Charles Walters, a hit-or-miss studio technician (Please Don't Eat the Daisies, Walk, Don't Run) is far too square in his approach to wrest any additional laughs out of the material. His shooting style (even given the technical drawbacks of early CinemaScope) is straight-ahead proscenium stage framing, and becomes quite dull over time. And what the slight material of The Tender Trap desperately needed was not a dull director.

THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM

A sensation when released, and considered another feather in the cap of iconoclast director Otto Preminger (who released the film without a MPAA seal - almost unheard of at the time), The Man With the Golden Arm, loosely based on the award-winning novel by Nelson Algren, tells the story of former drug addict Frankie Machine (Frank Sinatra). Newly released from a prison hospital, he's kicked his heroin habit and returns to his squalid Chicago neighborhood. Meeting his friend Sparrow (Arnold Stang), who earns his pennies selling stray dogs, Frankie is welcomed back by the old gang, but Louie (Darren McGavin), Frankie's pusher, feels confident that Frankie will be back on the smack in no time. Eventually, Frankie makes it back to his crummy little apartment, where his wife Zosh (Eleanor Parker) waits for him. Bound to a wheelchair after a car accident, the clinging, whining, terrifically jealous Zosh doesn't want to hear about Frankie's plans to make money drumming so he can get a proper doctor for Zosh's ailment. She's terrified of Frankie leaving her, and is desperately frightened of Frankie's wish to get away from the old neighborhood (his doctor in prison told Frankie that if he didn't change his environment, he'd soon go back on the horse).

Complications immediately arise when Sparrow steals a suit for Frankie (who had an interview to audition for a big band). Picked up by the cops, Frankie misses his appointment, and reluctantly falls back in with Schwiefka (Robert Strauss), the bookie who used to hire Frankie to deal for all his poker games. Despite all his best efforts, and even the calming effects of former lover Molly (Kim Novak), he quickly gets hooked again, blowing another chance to audition for a big band. Spiraling down into worse and worse addiction, Frankie's world comes undone when someone kills Louie. Will Frankie finally kick his habit?

SPOILERS ALERT!

Considered more than daring when it premiered in 1955 (no major Hollywood film with A-list actors had ever tackled drug addiction as its main story line at this point), The Man With the Golden Arm was considerably lightened up by screenwriters Walter Newman and Lewis Meltzer from the original grim, fatalistic, Algren novel. After decades of numerous more graphic depictions of drug addiction on the big screen, The Man With the Golden Arm may seem today a tad naive and basic, but there's no denying that director Preminger perfectly captures the utter fatalistic dread that starts almost immediately in the film, with the viewer wondering not if Frankie is going to fail, but when and indeed, how often.

And Sinatra deserves a lot of the credit for this sustained anxiety with his astonishing performance. Sinatra himself claimed this was his best role, and he may be right. Certainly, he'd never allow himself to be this open, this emotionally naked again on camera. Sinatra's aversion to rehearsals or multiple takes was legendary in Hollywood, and his insistence on getting everything done on the first take increased as he got older. If his one-take technique was utilized during this shoot, then his final performance is all the more remarkable because he doesn't hit a false note here. Equally good (although nobody seems to ever talk about her performance) is Eleanor Parker in what may be the sickest, most horrifying wife ever captured on film. Pretending to be crippled to hang onto Frankie, Zosh is a terrifying energy-sapper, feeding on Frankie's lifeforce like a vampire to ensure he stays good and guilty and never leaves her. Parker is excellent cutting off Sinatra when he's trying to express some modicum of feeling or personal thought - she's not interested in a true relationship; she wants to control it, manage it, and shape it to her grasping needs. It's a tour de force for Parker that unfortunately didn't lead to any similarly worthy roles

However, seen today, there are drawbacks to The Man With the Golden Arm which seriously diminish its original impact. Significantly, the stage-bound production (all of it was shot on a soundstage) looks decidedly fake today, with the film's visual design failing to match up with the grittiness of the performances. Where is Preminger's noted visual mastery here? If any film needed to be shot on the real streets of Chicago, it's The Man With the Golden Arm. Whether due to budgetary restrictions or Sinatra's noted dislike of shooting on location, the choice to shoot The Man With the Golden Arm on a soundstage seriously dates it, and compromises its claim to authenticity.

As well, the original story has been so compromised (no doubt due to censorship restrictions - despite Preminger pushing the envelope with the MPAA) that what should have been a fatalistic, ultimately downbeat indictment of drug addiction and poverty, instead trades on easier dramatic complications like Frankie's romance with Molly (played without conviction again by Kim Novak), and suspense over whether or not everyone is going to figure out Zosh's secret. Relying more on convention plotting, The Man With the Golden Arm seals the cop-out deal by giving Frankie and Molly a happy ending (he hangs himself in the novel), complete with Zosh conveniently committing suicide to clear the decks for the happy kids. Luckily, composer Elmer Bernstein's scintillating, pulsating score contributes a measurable dose of sickening moxie to the film, lifting Sinatra's scenes of addiction to a credible approximation of Algren's intentions. It's one of the best scores of the 1950s, and deserves as much credit as Sinatra's performance, for what succeeds in The Man With the Golden Arm.

SOME CAME RUNNING

An impressive drama for first-time viewers (that unfortunately doesn't bear repeat viewings), Some Came Running is probably more widely known today for being the "official" start of the Sinatra "Rat Pack," rather than as Sinatra's attempt to wrest a second Academy Award by starring in another adaptation of a James Jones' novel. Sinatra, having won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for Jones' From Here to Eternity, had becomes friends with the author, so it seemed a natural for Sinatra to star in Jones' sophomore effort - even though the book was roundly panned by the critics, and the title role - failed, struggling author and WWII vet Dave Hirsch - was a stretch for Sinatra. Filmed down in the small river town of Madison, Indiana to much publicity fanfare, Sinatra caused quite a bit of a ruckus in the sleepy little town, angering the locals and generating enough negative publicity that Life magazine sent down a reporter to see what all the hubbub was about. Though their reporter didn't get much of a story (the stars refused to talk with him), the reporter did coin a label for Sinatra's group, "The Clan," that stuck with Sinatra, one which he and his group used until the more P.C.-friendly "The Rat Pack" was adopted. This labeling of the whole Sinatra gestalt at this period in his career helped America define its attraction to the star and his way of life, and continues today to define the man and artist (rightly or wrongly). This beginning of "The Rat Pack," as well as the now-oft told tales of artistic conflict between Sinatra and Martin versus their director Vincent Minnelli, define Some Came Running today, with the movie itself and its artistic merit coming in a poor second for the few who have even seen it.

It's 1948, and Dave Hirsch (Frank Sinatra), a newly discharged WWII vet finds himself arriving at his home town of Parkman, Indiana, after his Chicago buddies put him on a bus when he was loaded. Not sure exactly why he's there, he's more than surprised to find an unexpected traveling companion: tramp Ginnie Moorehead (Shirley MacLaine), who has followed Dave from Chicago merely because he acted nice towards her. Wanting to ditch her right away, he gives her a quick $50 for bus fare and books a hotel room, making sure to deposit his substantial wad of $5500 (earned from gambling) in one of the town's two banks - the bank that his brother Frank (Arthur Kennedy) isn't affiliated with on the governing board.

Frank, a prominent local businessman, is embarrassed by the return of Dave, and Dave's spiteful slam with the bank deposit (particularly since he didn't have any advanced warning), but he puts on his best phony, insincere face and welcomes Dave back like the prodigal son. But Dave is having none of Frank's hypocrisy. Agreeing to meet a niece he's never seen before later that night at Frank's, Dave heads for Smitty's Bar, where he meets gambler Bama Dillert (Dean Martin). Fast friends right from the start, Bama invites Dave to gamble with him that night, after his dinner with Frank. At dinner, Dave meets invited guests Gwen French (Martha Hyer) and her father, Professor Robert French (Larry Gates). Gwen, who's read everything Dave wrote prior to the war, is a cool customer, which presents a challenge to Dave. Hoping to use the fact that he has an unfinished manuscript for a story he wrote before the war, Dave looks forward to breaking down Gwen's reserve.

However, the seedier side of Parkman calls to Dave, as well, and soon, he's gambling with Bama and keeping company with Ginnie, who didn't leave town but instead got a job at the local brassiere factory. Complications arise in Frank's troubled marriage, with Frank's gorgeous secretary, Edith Barclay (Nancy Gates), at the center, while Dave's pursuit of Gwen is frustratingly close to success - particularly after she deems his manuscript perfect for publishing. But the specter of doom looms in Parkman - in the guise of Ginnie's ex-boyfriend Raymond (Steve Peck) - with a shattering conclusion once the carnival arrives for Parkman's centennial celebration.

SPOILERS ALERT!

While I almost always resist the temptation to discuss a movie adaptation of a book in regards to its fidelity to the source material (they're two separate aesthetic experiences), it's difficult for me to do so with Some Came Running because I admire the book so much, and after numerous repeat viewings, am disinclined to think the same of the film. I was introduced to the movie first back in college by a film professor who got me hooked on a Vincent Minnelli kick. While most admirers point to his musicals, I was particularly taken with his gorgeous, widescreen, almost baroque, color-soaked melodramas from the 1950s (Home from the Hill, The Cobweb). And upon first viewing, I certainly took Some Came Running (or at least its final carnival sequence) as part of that general aesthetic. After watching it, I tracked down a copy of Jones' massive tome (it's something like 1200 pages), and spent the summer getting through it. It's a particular favorite of mine now (despite the really hostile reviews it received and the fact that almost nobody bothers to read it or even mention it today), with Jones, in his purposefully overwritten, idiosyncratic style, giving an overwhelming, almost cosmic view of postwar small town America, centered by a disturbing, nightmarish depiction of a writer spiraling down into the abyss, who is almost saved from fate by a friendship with a gambler.

Unfortunately, most of that is utterly lost in Minnelli's Some Came Running. Instead, we have a rather conventional Peyton Place knock-off (the included original trailer screams that this is an expose in that latter fashion), coupled with the returning troublemaker-making-the-hometown-squares-nervous subgenre. Too much of Jones' intentions are lost here, to be replaced with facile plot conventions borrowed from other, better films. Jones' tortured writer finds temporary redemption through a chaste, impossible love with schoolteacher Gwen French, as well as with laconic gambler Bama (who remains essentially unknowable and unreachable even to Dave). But here, Dave gets to bed Gwen (or at least that's the strong implication in 1950s film code), only to lose her when she finds out he's sleeping with Ginnie. And Dave's destruction in the book comes directly from his ill-fated marriage to Ginnie - who truly is a pathetic, but largely unsympathetic character. But here in Minnelli's more conventional world, Dave gets to be magnanimous and save poor Ginnie-the-tramp-with-a-heart-of-gold (who is designed by the screenwriters and played by MacLaine much too sweetly), even grieving over her poor dead body when she's shot by her boyfriend - a major disruption of Jones' intentions which occurred when Sinatra, who was supposed to die in the script, gave the death scene to MacLaine to beef up her role. The doom that permeates the novel, and which seems to be coming for Sinatra in the film, is neatly avoided by Ginnie's death. Everyone gets to grieve, and feel superior (even Gwen, who was repulsed by Ginnie, comes to the funeral, secure in her pity now that she's dead). The complexity of Jones' vision is negated with easy, cheap pathos.

As well, Sinatra is fatally miscast as Dave - something that Jones reportedly felt, as well. Physically a 180-degree departure from the novel Dave (who's almost rotund and who wears only work clothes or his uniform), reed-thin Sinatra shows up in various cardigans (which reportedly sent Jones out of the screening room, disavowing the film outright) and Hollywood tailored suits, never convincing us that he's in any way a struggling writer. It's important, too, to realize that at this point in Sinatra's career, he was the single most popular entertainer in the world. His records and films were number one on the charts, and his life was the subject of constant gossip. The tentative, anxious Sinatra of the early fifties, who couldn't get booked for a singing gig when his throat gave out, was long gone. This is the powerful, confident Sinatra, the Sinatra that didn't care for his director's "prissy" ways (most sources identify Minnelli as a homosexual, although some close to him deny that). And this confidence, this power, is evident in his portrayal - which is exactly what the Dave Hirsch character doesn't need. Sinatra, no doubt employing his standard "one-take" demands (and screw the other actors who don't keep up or who flub something), is instinctually on the mark, but it's a careless, almost rote performance here, and ultimately of little substance.

As well, the shaky script construction jumps from scene to scene, sometimes with little grounding for the audience to get their bearings; one moment Dave is trying to put the moves on Gwen, and in his next scene with her, he says he loves her - with nothing in-between to indict how he got to that emotion. As for the film's subtext of "exposing" small-town hypocrisies, that message wasn't terribly original in 1958. America's small towns had been skewered in many other literary works, and films all the way back to the silents had taken small town prejudices to task for comic and dramatic effect. Indeed, despite a few modern critics who see Some Came Running as some kind of benchmark in such muckraking, there's very little actual satire or commentary on such matters in the film. Certainly Kennedy's Frank Hirsch provides most of that context, and he's the best thing in the film. Kennedy excelled in these kinds of overripe melodramas (Peyton Place, A Summer Place), and here, he's nauseatingly effective as the appearances-obsessed Frank Hirsch, who calls his wife "Mama" and says he likes his girls "giggly." His performances so outweighs Sinatra's that it's not surprising that he has only one or two scenes with him before being relegated to the background in favor of Martin clowning around with Sinatra.

However, despite all these drawbacks, it's understandable that the film still carries a sizeable reputation among film fans, perhaps for nothing else than Minnelli's final sequence where Ginnie's killer boyfriend stalks Dave through an increasingly frenzied carnival. Employing all his powers of widescreen composing and theatrical, almost operatic lighting effects, Minnelli delivers a nightmarish visual descent into madness that's all the more ironic considering the setting is an innocuous small-town carnival. With Elmer Bernstein's pounding, driving, doom-laden music in the background, Minnelli's camera tracks along relentlessly, pinning Dave and Ginnie down within the wide CinemaScope frame, as Raymond keeps popping up in ghoulish silhouettes against garish-colored spots (his appearance in Dave's room, silhouetted in absolute black against a rich red background, is stunning). Minnelli, utilizing the work of master cinematographer William H. Daniels, creates a kaleidoscopic, exhilarating frenzy that stops me short every time I see it. It's truly a remarkable sequence (brilliantly edited by Adrienne Fazan), and one of the best examples of widescreen color compositions and montage in American film. If for nothing else than this final arresting, disturbing sequence, Some Came Running is well worth watching.

NONE BUT THE BRAVE

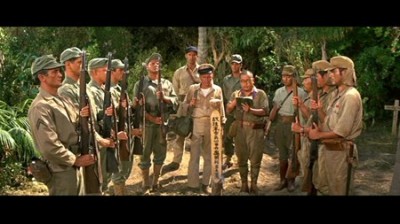

Sinatra's first release for 1965 (and quite inferior to his second, the superior actioner Von Ryan's Express), None But the Brave has the distinction of being the only film Sinatra ever directed. But this timid, low-budget, strangely-toned chamber piece masquerading as a 1960s WWII action flick is largely unsuccessful due to a poor Sinatra performance and a questionable approach to the material. Sinatra plays Navy Chief Pharmacist Mate Francis (the film doesn't say whether this is his first or last name), who is catching a ride on Captain Dennis Bourke's (Clint Walker) plane, which is transporting some Marines to the front. Following an air battle with a Japanese Zero, the plane crash-lands on a seemingly deserted island in the Pacific (it lies outside the main sphere of naval combat). Unfortunately, the island is inhabited by a small squad of Japanese soldiers who have been cut off from their unit due to the island-hopping American forces. Led by sensitive, humanist writer/warrior Lt. Kuroki (Tatsuya Mihashi), the Japanese soldiers have been planning on leaving the island once their hand-made boat is finished. But with the arrival of the Americans on the island, an uneasy truce is eventually reached between the warring factions - until the realities of war necessitate the revocation of this unusual detente.

SPOILERS ALERT!

Themed not unlike the later, superior Hell in the Pacific, None But the Brave obviously wants to have an even-steven approach to its obvious anti-war message, showing the Japanese soldiers as complete equals to the American men. And any lingering memories for American audiences who remembered horrific Japanese atrocities is balanced by portraying the harsh, angry, violent Japanese officer, Sergeant Tamura (Takeshi Kato) as having an equally bloodthirsty American opposite number, Second Lieutenant Blair (Tommy Sands). No doubt this U.N. approach to the story was served well not only by Sinatra's then-liberal leanings, but also by the fact that None But the Brave was an official co-production between Warner Bros. and Toho Films.

What sinks None But the Brave is Sinatra's rather strange, haphazard treatment of the material. Weirdly comic at times (particularly with his careless performance), one never knows when None But the Brave is going to be serious or funny. One moment Sinatra is acting not unlike one of his characters from his "Rat Pack" movies, giving ramrod psycho Blair a hipster slap to the face while flashing a jaunty movie star smile, and the next, someone is delivering yet another obvious, marginal moral observation about the senselessness of war. He's barely in the film, too (perhaps the directing duties necessitated cutting down the role?), saving for himself a big, cliched battlefield operation scene we've seen a hundred times before. Declarative exposition abounds in None But the Brave. We see a scene and immediately get its intent, only to have a character then tell us exactly what we just saw and exactly what it meant. After the final scene fades out, a text graphic comes up that states, "Nobody Ever Wins," the kind of facile, juvenile statement that sounds deep and meaningful and world-weary, but upon one minute of reflection comes up as obvious and manipulative. Sinatra and his screenwriters seem to want to reduce all war conflicts to senseless Mexican standoffs that would be simply solved if we all just talked to each other and shared our feelings. But it's a simplistic attitude to an infinitely complex theme that ignores those cultures and soldiers who actually did win wars, and whose efforts and sacrifices actually did make a difference for hundreds of millions of people - such as the victors of WWII that Sinatra is depicting. Sometimes in war, somebody does win - and for a very good reason. Ham-handed dramatics, with simplistic proposition and conclusions, would have made None But the Brave amusing had it not taken itself so seriously in total. But instead, the tone of the piece is all over the place, ultimately leaving the viewer adrift in uncertainty.

The actual production of None But the Brave leaves a lot to be desired, as well. Sinatra as a director is the very definition of an anonymous camera-pointer, never managing to inform his frame with the slightest bit of subtextual meaning. Actors are put squarely in the middle of the expansive CinemaScope frame, and they deliver their lines to the rhythmic over-the-shoulder POVs and the master shot, two-shot, close-up editing. Two flashback scenes are tacked on towards the end of the film (to give us, supposedly, a deeper understanding of Bourke's and Kuroki's psychology), but they're so laughably constructed (Bourke is tormented because...he dumped his girlfriend...who ran off into the jungle...only to get blown apart with a direct hit from a bomb!) that we can't take them seriously. Sinatra seems to have no sense of subtlety or nuance, preferring to directly address the audience and make sure we get what he's saying (recounting the Bourke story, Sinatra literally looks right out into the audience).

He doesn't seem to have much more luck with the battle scenes, either (if he indeed staged them or if they were supervised by a second unit director). Tentative and poorly blocked, they add zero lift to the proceedings, while providing unintentional laughs when that's the last thing this film needs. The final shootout between the squads looks almost like something from Police Squad!, as Sinatra fails to establish any distance between the two firing groups - they look like they're standing five feet apart. Matching the inept special effects (widescreen monitors now clearly pick up the black heavy wires that hold up the planes, nor is the tidal wave particularly impressive) is perhaps one of the funniest (unintentional) performances of the 1960s - Tommy Sands' portrayal of Blair. It's hard to say whether or not anybody knew he was coming off the way he was during the shoot (didn't somebody watch the dailies), but I can only suppose Sinatra meant for his son-in-law to sound this way, because it's the broadest, most inept, most outrageous "military officer" characterization I've ever seen (he often sounds as if he's suffering a stroke). His wildly-off tone performance perfectly sums up this seriously misguided, obvious, slipshod effort.

MARRIAGE ON THE ROCKS

Surely one of the worst romantic comedies of the 1960s, Marriage on the Rocks was Sinatra's third effort for 1965, and clearly by this point in his film career, he should have turned down tripe like this to save his considerable talents for quality projects. Unfortunately, the prospect of making easy money by goofing around with his "Rat Pack" buddies for a couple of weeks proved too attractive for the coasting star, with the result being that Sinatra closed out his acting career with far too many stinkers like Marriage on the Rocks.

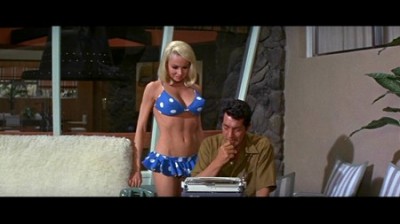

The ridiculous plot for Marriage on the Rocks goes like this. Sinatra plays (rather incongruously) Madison Avenue ad man Dan Edwards. A workaholic, Dan thinks of himself as a great father and good husband. But his wife, Valerie (Deborah Kerr, looking totally lost), is bored to tears with the "new" Dan who would prefer watching color TV at night with her live-in, bagpipes-playing (I'm not kidding) mother-in-law, Jeanie MacPherson (Hermione Baddeley), than make love to her. She wants the "old" Dan back, the hell raiser of their youth who liked to dance and drink and go out every night - exactly like confirmed bachelor Ernie Brewer (Dean Martin), who works for Dan and whom Valerie almost married before Dan. Ernie, complete with swinging bachelor pad and a stunning array of office secretary hopefuls he constantly interviews, is in reality, though, jealous of Dan's settled life - or at least he says he is.

Convinced by Ernie to take Val on a Mexican second honeymoon, a misunderstanding by the couple results in a quickie Mexican divorce. Dan leaves for New York on business, but agrees to come back and re-marry Val. But complications arise, and he sends Ernie down instead, to tell Val he'll be a few days late. Of course, as you've already guessed, Ernie and Val somehow mistakenly get married, and now it's time for the boys to experience how the other half lives, with Ernie now saddled with Val and Dan's troublesome kids, and Dan making nice with his daughter Tracey's (Nancy Sinatra) nubile go-go dancer pal, Lisa (Davey Davison).

SPOILERS ALERT!

Written by Cy Howard (That's My Boy) and directed by veteran TV director Jack Donohue, Marriage on the Rocks plays like the Rat Pack meets Doris Day and moves over to Make Room for Daddy. Coming out when these kinds of films were increasingly stiffing at the box office (even Doris' were cooling off), it's obvious that Marriage on the Rocks wants to straddle some kind of gap between the earlier Day romantic comedies of the early sixties, and the coming counter-culture that's briefly alluded to in the film (the go-go dancing club, Lisa as a disaffected youth). But none of it works because at its core, Marriage on the Rocks simply isn't funny. Not then (it flopped at the box office), and not now. There's much dialogue, and face-pulling, and people wildly gesticulating, but there isn't one truly funny line in the whole lame set-up.

It certainly doesn't help that Sinatra and Kerr are badly miscast here. Kerr, who could be very funny when her classy English persona was used for low-brow counterpoint (Casino Royale, for instance), isn't the first person one thinks of when headlining a Hollywood romantic comedy, though, and her chemistry with the rough-and-tumble Sinatra seems based more on fear than amusement or sexual attraction. Kerr often looks like a deer caught in the headlights around Sinatra, although she noticeably relaxes with the smooth, easy, funny Dino. As for Sinatra, it's obvious, in his three-piece Brooks Brothers suits and carefully modulated business tone, that he's trying for Cary Crant in That Touch of Mink, but what comes out, over and over again, is That Smell of Hoboken. As soon as he's with Dino in a scene, his characterization goes right out the window, and he's laying down hep-cat lingo in an almost snarly, ticked-off voice that has nothing to do with Madison Avenue. Worse, as Dino often said time and time again, Sinatra couldn't tell a joke to save his life; he's just not an instinctively funny performer, and his flat, sour turn here is a big letdown (although admittedly, he is funny when he's in bed, whining that he's sick, or when he does a mean frug in a go-go dancing cage).

Of course, Dino is effortless in this kind of film; this is his territory, and he's obviously having a lark, playing around with his line deliveries and trying to inject something, anything into the proceedings to have some fun. But ultimately, he looks bored, too, and when the script calls for him to do asinine things like put his leg in a cast to ward off the advances of newly married-to Kerr - when the film doesn't indicate that she'll attack him in the slightest - it's demeaning treatment of a gifted farceur. Along with Dino, about the only bright spot is Caesar Romero in an amusing bit (that goes on too long, of course) as a one-stop divorce/marriage official down in a sleepy Mexican town. He's got a lot of energy, and quite frankly, a movie about his character would have been a welcome respite from the cliched romantic comedy stereotypes of Kerr, Sinatra and Martin.

The movie's message, of course, conforms strictly to established mid-60s Hollywood "battle of the sexes" comedies: in other words, Kerr, the instigator of the trouble (she's bored with her marriage), has to suffer for her crime of upsetting the domestic bliss of her household. So, for her troubles, the script ultimately rewards Sinatra - the offender who ignores his wife and refuses to have sex with her - by transforming him into a better father to his kids, while Kerr, in her final scene, loses everybody at Thanksgiving because she's at fault for the entire mess. Naturally, Sinatra gets to be magnanimous and forgive the crying Kerr - but only after she's sat for a minute or two at the table, alone, thinking she's lost everything. Women today might watch Marriage on the Rocks and stare in total disbelief.

The DVDs:

The Video:

For the most part, all of the video transfers for the Frank Sinatra: The Golden Years boxed set look particularly good. First, all are anamorphically enhanced for 16:9 TVs. Second, all the titles, except for The Man With the Golden Arm are presented in their original CinemaScope ratios of 2.35:1. These titles look remarkably bright and clear, with super-sharp pictures, little or no compressions issues I could spot on my widescreen monitor, and gorgeously hued color values. Bit rates are more than adequate. As for The Man With the Golden Arm, my understanding is that the film has been in public domain for quite some time. I don't know if Warners was able to go back to the original source material, but the matted letterboxed image here (at 1.85:1) looks a little tight to me, with heads slightly cropped at times which would seem unlikely for Preminger. As well, there is grain and a surprising amount of scratches (including a big white one running at the beginning of the film) that indicates to me that either the original source materials are compromised, or more likely, Warners had to go with a beat-up print. Still, it looks far better than the print I've seen it on TCM lately, so overall, it's a positive.

The Audio:

Disappointingly, only The Tender Trap is presented in Dolby Digital English Surround 5.1 (which sounds quite nice during the musical numbers). And None But the Brave features a Dolby Digital English 2.0 stereo mix that's adequate for the battle scenes (and no more). Distressingly, the other titles are released in Dolby Digital English mono mixes - which is particularly harmful to the stellar Elmer Bernstein compositions in The Man With the Golden Arm and Some Came Running. English, French and Portuguese subtitles are available for The Tender Trap, Some Came Running, and Marriage on the Rocks. English and French subtitles are available for The Man With the Golden Arm, and English only subtitles are available on None But the Brave.

The Extras:

Some interesting extras accompany the Frank Sinatra: The Golden Years. The Tender Trap includes an interesting new documentary, Frank in the Fifties, running 15:58, that examines the Sinatra mystique, as well as his cinematic and musical efforts during his comeback decade. An original theatrical trailer is also included. The Man With the Golden Arm includes Shoot Up, Shoot Out: The Story Behind "The Man With the Golden Arm," a new documentary on the making of Sinatra's favorite film, that runs 19:25. It's a good accounting of the cast and crew that went into this seminal production. An original trailer is also included. Some Came Running also has a newly created behind-the-scenes documentary, The Story of Some Came Running, running 20:35, which includes some questionable evaluations of the film, but which provides some good background info for fans. An original trailer is also included. For None But the Brave and Marriage on the Rocks, only original trailers are included.

Final Thoughts:

Fans of Frank Sinatra's film work will no doubt want to include Frank Sinatra: The Golden Years boxed set into their collection. All the titles are first time to DVD (except for The Man With the Golden Arm), and the transfers are for the most part, excellent. A few new behind-the-scenes documentaries will be of interest to Sinatra completists, making the Frank Sinatra: The Golden Years recommended viewing.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published film and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||