| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

How the West Was Won

Warner Bros. // G // September 9, 2008

List Price: $59.98 [Buy now and save at Amazon]

Ladies and gentlemen, this is Cinerama!

Ladies and gentlemen, this is Cinerama!Throughout the 1950s, Hollywood studios went to war against the new threat of television, delivering a new form of cinema that was bigger, bolder, grander. Just as today's multiplexes battle the internet with digital 3-D and IMAX, theaters of the 50s offered audiences movies that were larger in every sense: oversized epics designed to showcase ever-increasing screen sizes.

And no screen was bigger than Cinerama. Premiering in 1952 with the travelogue "This is Cinerama," the format used three projectors to create a mammoth widescreen image on a 146-degree curved screen, with seven speakers placed throughout the theater creating dynamic surround sound. The three cameras used in filming were designed to capture a remarkably high depth of field, allowing the background to remain in as sharp a focus as the foreground.

"This is Cinerama" was a smash, becoming the top money-maker of the year despite playing in a limited number of theaters. Just as IMAX is devoted mainly to documentaries today, Cinerama spent the next decade as a format for big-scale roadshow travelogues with titles like "South Seas Adventure" and "Seven Wonders of the World." It wouldn't be until 1962 when the format would take the leap to dramatic storytelling - a short leap, ultimately, as only two features would be created for the three-strip process. (Later films, ranging from "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World" to "2001: A Space Odyssey," would carry the Cinerama label, but they used a single-camera 70mm technique that was created in response to the rising costs of three-strip production.) Both films were huge hits: first was "The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm," which retold classic fairy tales in grand style, and then came "How the West Was Won."

Billed as featuring "24 Great Stars" (not to mention the dozens of top-level supporting players) and utilizing four directors (one of them uncredited), "How the West Was Won" is the sweeping epic of several generations of a family moving ever westward, encountering all the tribulations the 19th century had to offer. The film features several action set pieces designed specifically for the grandeur of Cinerama, yet it balances these with small-scale personal drama, each delicately handled, overcoming the supposed limitations of up-close storytelling in the three-strip process.

The screenplay, by James R. Webb and an uncredited John Gay, divides its tale into five chapters, labeled in the opening credits as "The Rivers," "The Plains," "The Civil War," "The Railroad," and "The Outlaws," each showing a progression of the American west from a frontier wilderness in 1839 to a land increasingly conquered and tamed in 1889. (An epilogue reveals then-modern day Los Angeles and San Francisco, revealing the aftermath of such Manifest Destiny.) Spencer Tracy offers the narration that links these stories, offering commentary on the changing nature of the west and the perseverance of American spirit.

As the film opens, the west isn't so wild, with mountain men like fur trader Linus Rawlings (James Stewart) at perfect peace with the open country and the Native tribes who were here long before the white man. This seems to be the overriding theme of the film: the west was just fine before we sprawled out. The subversive nature of such a theme undercuts the more traditional cowboys-and-injuns genre elements and the "America the Beautiful" ideals that often come with them. Throughout the film, characters bemoan the ideas of westward expansion, glory in battle, and national pride; triumphs are chalked up not to American gumption but a more universal human determination. This makes the modern California epilogue a conundrum - what would wily buffalo hunter Jethro Stuart (Henry Fonda), the man who said the railroads would bring nothing but trouble to the Pacific - think of these final shots of four-lane highways and towering skyscrapers? Was that the trouble he had in mind, or does this urban footage show a conquering of that trouble, a sophisticated step beyond the wild days that initially followed westward expansion?

As the film opens, the west isn't so wild, with mountain men like fur trader Linus Rawlings (James Stewart) at perfect peace with the open country and the Native tribes who were here long before the white man. This seems to be the overriding theme of the film: the west was just fine before we sprawled out. The subversive nature of such a theme undercuts the more traditional cowboys-and-injuns genre elements and the "America the Beautiful" ideals that often come with them. Throughout the film, characters bemoan the ideas of westward expansion, glory in battle, and national pride; triumphs are chalked up not to American gumption but a more universal human determination. This makes the modern California epilogue a conundrum - what would wily buffalo hunter Jethro Stuart (Henry Fonda), the man who said the railroads would bring nothing but trouble to the Pacific - think of these final shots of four-lane highways and towering skyscrapers? Was that the trouble he had in mind, or does this urban footage show a conquering of that trouble, a sophisticated step beyond the wild days that initially followed westward expansion?Of course, the wilderness of 1839 was far from a paradise. Linus encounters a family of settlers, the Prescotts, embarking down the Ohio River in search of new land. He instantly falls in love with daughter Eve (Carroll Baker), but their romance is interrupted by adventure as pirates attempt to murder Linus and later assault the Prescotts. Later, in a scene tailor made for the big, big screen, the family gets caught in white water rapids. So much for the narrator's depictions of a peaceful west.

Jumping ahead a few years, the film picks up with Eve's sister Lily (Debbie Reynolds), now living as a dance hall girl in St. Louis. It's there she meets roguish gambler Cleve Van Valen (Gregory Peck), who escorts her on a wagon train to California when she learns of a gold inheritance. Wagonmaster Roger Morgan (Robert Preston) does his best to woo her, but Lily will have none of either man. An attack on the wagon train by Cheyenne Indians is the intended centerpiece of this episode, and it's a whopper (Henry Hathaway helmed this as well as "The Rivers" and "The Outlaws," putting him in charge of the film's three biggest action sequences, all of them brilliant in their use of the widescreen format, creating perfect tension and thrills), yet the real strength of this chapter is its human angle. Lily's love story is tender and bittersweet, with a fabulous conclusion, all ensuring the personal core of the film never gets buried under all the Cinerama spectacle. Better still, Hathaway does a superb job of working around the limitations of the Cinerama process (with its potential for awkward-looking close-ups and unnatural staging). The vastness of the image eventually enhances the intimate scenes, revealing a sense of grandeur that gels wonderfully with the bigger action scenes.

Following an intermission (whew!), we pick things up with the Civil War, with John Ford directing. Ford was uncomfortable with the Cinerama process, and it sometimes shows, with cramped compositions and actors crammed into the middle frame of the picture. (Placing both actors in the middle of the three frames was the best way to keep their performances natural; otherwise, to create the appearance of a character in the far left panel talking to another on the far right, the actors had to stand at odd angles and look away from each other, which hindered the natural tones of the drama.) Ford overcomes these issues by focusing the story's attention on the small scale, a brilliant directorial choice. Sure, the Battle of Shiloh is another piece of impressive spectacle (using footage leftover from previous MGM production "Raintree County," reformatted for Cinerama), but the chapter works best in its quiet moments between two players.

The chapter follows Zeb (George Peppard), Linus and Eve's now-grown son, as he joins the Union Army in hopes of finding adventure and an escape from the dull farming life. But what he finds in war is far from glorious. Following the bloodshed of Shiloh, Linus encounters a Confederate deserter (Russ Tamblyn), and they ponder the futility of it all. Shouldn't they be killing each other? They sure don't want to.

The chapter follows Zeb (George Peppard), Linus and Eve's now-grown son, as he joins the Union Army in hopes of finding adventure and an escape from the dull farming life. But what he finds in war is far from glorious. Following the bloodshed of Shiloh, Linus encounters a Confederate deserter (Russ Tamblyn), and they ponder the futility of it all. Shouldn't they be killing each other? They sure don't want to.The weariness of battle is also not lost on Ulysses S. Grant (Harry Morgan) and William Tecumseh Sherman (John Wayne), shown here as two generals bruised by a life of war. Far from the glamour of the history books, the film bravely shows Grant as a drunkard whose habit nearly lost him the war. It's a somber moment in an episode full of them; the dreadful aftermath of that discussion, plus Zeb's quiet return home, add up to a damning depiction of war, right where you'd least expect it, in a mainstream American western.

George Marshall takes over directorial duties for the next chapter, which studies the rise of the railroad and permanent impact, for better or worse, on the west. In the struggle to be victorious in the company wars of the era, sinister railroad man Mike King (Richard Widmark) works his men literally to death - when buffalo hunter Jethro Stuart, hired to clear the land for the railroad crews, gathers the corpses of men killed by Indians, King berates him for the wasted time and effort. (Better bury them where they fall and get back to work, he coldly insists.)

Fonda is given plenty of room to discuss the dangers of expansion; his character loathes King and all he stands for. Does the west need to be shaped like the states back east? Isn't it doing just fine without big cities and big commerce? When King reneges on a treaty and begins building on Arapaho land, we see Stuart as right.

And when the Arapaho retaliate by unleashing a deadly buffalo stampede through the railroad camp (this segment's key action showpiece), it's not because of some cold-blooded injun villainy. The Arapaho attack because they were provoked - the real villain is King. And what a villain. Widmark is marvelous here, his steely-eyed refusal to budge revealing a corporate callousness that one could argue mirrors the ethics of today's conglomerate-centric world. Stuart and Zeb (who accompanies the buffalo hunter on several adventures) provide this chapter's moral center, denouncing the railroad's progress while ultimately being unable to stop it.

Lily, now much older and wiser (with Reynolds working under very convincing make-up, one of the film's countless technical achievements), returns for our final chapter. We catch up with her following the death of her husband, and her laid-back attitude toward her lost riches is endearing. (They made and spent several fortunes, she says with a wink, and had he lived, they'd only have made and spent another.) Having lost her estate in San Francisco, she journeys to her last possession, a ranch in Arizona, inviting nephew Zeb, now married with children, to help tend the land.

But with the railroads came outlaws, proving Stuart right one last time. This is the 1880s, the wildest days of the wild west, when lawmen struggle to return peace to a land that was once celebrated for its lawlessness, now feared for it. Zeb is a marshal, and his travels to Arizona also lead him to an old enemy, Charlie Gant (Eli Wallach, in full-on bad-guy mode). This leads to our grand climax, as Zeb and fellow marshal Lou Ramsay (Lee J. Cobb) ambush Gant's men as the villains attempt to rob a train carrying a large gold shipment.

But with the railroads came outlaws, proving Stuart right one last time. This is the 1880s, the wildest days of the wild west, when lawmen struggle to return peace to a land that was once celebrated for its lawlessness, now feared for it. Zeb is a marshal, and his travels to Arizona also lead him to an old enemy, Charlie Gant (Eli Wallach, in full-on bad-guy mode). This leads to our grand climax, as Zeb and fellow marshal Lou Ramsay (Lee J. Cobb) ambush Gant's men as the villains attempt to rob a train carrying a large gold shipment.This final, oversized set piece ultimately abandons the dramatics, the intricate character work, and the social commentary, and simply and solidly plows straight ahead with pure, no-holds-barred action. It's a doozy of a whopper of a gem, one of the finest action sequences ever put on film, with shoot-outs and runaway trains and giant pieces of lumber swinging right out at you. And it's all done without the aid of modern effects, which makes the visuals all the more impressive, the stuntwork all the more daring. (And how: stuntman Bob Morgan nearly died filming this scene.)

While Tracy's narration, set to sweeping aerial images in the "This is Cinerama" mold (shot by an uncredited Richard Thorpe), ends the film on an up-with-America beat, transitioning to those curious shots of 1960s highways, the story receives a better, more touching, more honest ending in the moments just before it, as Lily and Zeb's family - including the fourth generation of Prescotts to endure and tame the west - ride off to their new home, singing the family song, a reworked version of "Greensleeves" that plays throughout the picture. The scene is genuinely moving as it ties together all the movie's episodes, bringing family unity to these adventures. Musically, the movie is always nothing less than thrilling (Alfred Newman and Ken Darby's themes remain among the grandest ever produced for film), and this little nod at the end, with the kids singing Lily's favorite tune, creates a lovely capper to this broad, bold epic, a story as big, as brash, and as exciting as the west itself.

The DVD

"How the West Was Won" has long struggled on home video. First on VHS, then on DVD, the Cinerama image looked downright terrible, as the seams between the three panels were always visible, often distractingly so. Worse, color tones and brightness levels of the three panels were often slightly mismatched. While having the film available in widescreen was a vast improvement over earlier pan-and-scan editions, such a problematic look left the film mostly unwatchable.

Now, finally, comes a version that works. The film has been fully restored a process that color-corrects each of the three panels per frame, allowing for a unified image; the three panels are then digitally "stitched" together to create a seamless single widescreen image. It's not always perfect - the seams still show, albeit only slightly, against the occasional blue sky or other light image, but only if you're really looking for them, and nothing nearly like it used to be. For the most part, the image seen in this restoration is nothing less than a revelation.

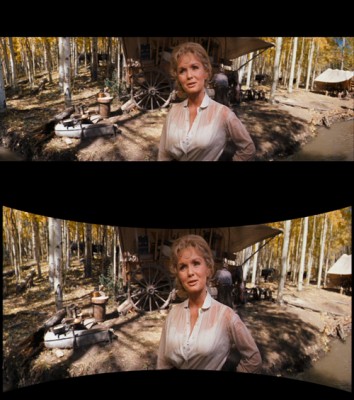

The other problem with adapting a Cinerama image to home video is the curve factor. By showing "How the West Was Won" on a TV monitor, you're essentially taking a curved image and flattening it out, which has the potential to distort the image of the far left and far right frames. (Of course, Cinerama was loaded with distortion problems every step of the way, as poor camera set-up could distort the shape of people and sets, and a bad seat in the theater could distort an audience member's perception of the action.) Cinerama filmmakers must contend with a "fish eye" look to their scenes.

To counter this at home, two versions of "How the West Was Won" have been crafted: one using a traditional letterbox technique, with the left and right panels adjusted to minimize distortion, and one using something called "SmileBox," which compensates for the fish eye look by simulating a curved image - tall on the edges, shorter in the middle. I prefer the regular letterboxing over the SmileBox look, although it could be because I'm accustomed to letterboxing, while the SmileBox version is distracting simply for its newness. (I'll add that the more I experience SmileBox, the more I get used to it, and the more I like it. Perhaps it's a matter of retraining the home video brain.)

Warner Bros. is releasing this newly restored edition of "How the West Was Won" in three flavors: a three-disc "Special Edition" DVD release, with the movie spread over two discs; a three-disc "Ultimate Collector's Edition" DVD set, featuring the same three discs, plus some nifty collectable trinkets; and a two-disc Blu-Ray package, which leaves out the trinkets but includes a 40-page making-of booklet. The standard DVD releases feature the film in its letterbox format, while the Blu-Ray release offers it in both letterbox and an exclusive SmileBox presentation, which is a nice touch.

Reviewed here is the standard DVD three-disc Ultimate Collector's Edition.

Video & Audio

As mentioned above, "How the West Was Won" looks jaw-droppingly spectacular in this new restored transfer, presented in 2.59:1 anamorphic widescreen. (Such a narrow image might be too tiny on smaller standard TV sets, but looks darn good on a widescreen monitor.) Dust and dirt have been wiped clean, leaving nothing but a crystal clear image, with brilliant colors and clean, clear lines. By spreading the movie across two discs (each half running about 80 minutes), there's plenty of leg room for the data, eliminating all compression issues. Any grumbles you might have over the few instances where the Cinerama seams pop up will be assuaged by the sheer richness of the rest of the picture.

The Dolby 5.1 remix of the soundtrack does a fabulous job of recreating the Cinerama sound experience, with rear speakers used for effects sequences and atmosphere without overdoing it. The dialogue seems a little undermixed when compared to the music and effects, but not enough to distract. An impressive French 5.1 dub is also included, as are optional subtitles in English SDH, French, Spanish, Japanese, and Thai.

Extras

Commentary throughout the film is provided by documentary filmmaker David Strohmaier, Cinerama Inc. director John Sittig, film historian Rudy Behlmer, music historian Jon Burlingame, and stuntman Loren James. The quintet bounce between prepared text and loose conversation with ease, each providing his own points of expertise, then pausing to share friendly discussion about the movie as a whole. It's a fabulous track all around, chock full of fabulous information and rich appreciation. Behlmer has long been one of my favorite commentary providers, informal yet informative, while Burlingame does a terrific job of shining new light on the film's use of music. Strohmaier and Sittig provide welcome information on the Cinerama process. Topping them all, of course, is James, whose easy-going remembrances of on-set adventure steal the show.

Commentary throughout the film is provided by documentary filmmaker David Strohmaier, Cinerama Inc. director John Sittig, film historian Rudy Behlmer, music historian Jon Burlingame, and stuntman Loren James. The quintet bounce between prepared text and loose conversation with ease, each providing his own points of expertise, then pausing to share friendly discussion about the movie as a whole. It's a fabulous track all around, chock full of fabulous information and rich appreciation. Behlmer has long been one of my favorite commentary providers, informal yet informative, while Burlingame does a terrific job of shining new light on the film's use of music. Strohmaier and Sittig provide welcome information on the Cinerama process. Topping them all, of course, is James, whose easy-going remembrances of on-set adventure steal the show.Disc One also includes the film's original trailer, which has not been restored and thus serves as a nice point of comparison for this release's visual upgrade. Presented in 2.35:1 flat letterbox.

Disc Three is devoted entirely to "Cinerama Adventure," Strohmaier's full-length (96 min.) documentary on the complete history of Cinerama. It is itself a monumental work, supplying detail after detail regarding the creation of the format, how the format works, its rise and eventual fall, and, most impressively, behind-the-scenes tales of several Cinerama films, including a thorough look at the making of "How the West Was Won." Presented in 1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen, with archival footage matted as needed, and with most Cinerama clips shown in the SmileBox format. Optional Japanese and Thai subtitles are included.

The "Ultimate Collector's Edition" presents these three discs in a trifold digipak that fits inside a handsome glossy cardboard slipcover. Also in that slipcover are two cardboard folders. The first folder contains twenty "collectable photo cards" - ten black and white cards featuring behind-the-scenes pictures, ten color cards featuring stills from the film for a sort of makeshift lobby card look.

The second folder includes a 20-page reproduction of the original Exhibitor's Campaign Book, which showcases posters to be ordered and potential news items to be included in the local paper; and a 36-page full-color reproduction of the Cinerama Souvenir Book sold during the film's roadshow tour. The latter is a real delight, really pumping up the showmanship of the movie's release, while the former has more limited appeal (especially since its small size leads to teeny print that will strain many fans' eyes).

(Also included, but not promoted, is an insert advertising a send-away offer for a free replica of the movie's poster. This is a limited time offer - expiring Nov. 26 - and will likely not be included in later pressings of this set.)

Final Thoughts

Finally, a tremendous movie gets a tremendous DVD release. This Ultimate Collector's Edition is nothing short of spectacular, earning its place in the DVD Talk Collector Series. While some of you may be satisfied with the discs-only version, and while some of you may prefer the SmileBox presentation available on Blu-Ray, there's no denying that this box set is phenomenal.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||