| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Murnau

THE MOVIES:

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau is one of the most heralded pioneers of early cinema. As part of the German studio system in the 1920s, he created a striking new style by employing lighting techniques that borrowed from expressionistic painters, creating an aura of mood and emotion unlike no other. He also pushed forward the use of camera movement and detailed sets, creating a more realistic and inclusive cinematic experience even as he often dealt in more remarkable subject matter. Across his early films, one can see themes of obsession, ambition, and secrets take shape, with his characters often succumbing to or dealing in trickery and challenging a fear (or at least distrust) of the unknown, sometimes in a supernatural setting. He also used the fantastic stories as a mode to critique the social and political mores of his time, an interesting and often troubling period of upheaval in his home country, between the defeat of World War I and the ugliness of World War II.

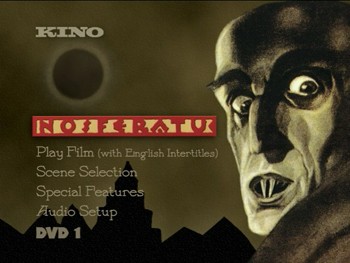

Kino's new boxed set, simply titled Murnau, brings together six of the director's silent films in one affordable package. Of the six, three are coming to DVD for the first time in the U.S. (and, just so you know, are also available separately in case you already own the other discs). These new releases are for the movies The Haunted Castle and The Finances of the Grand Duke and the complete German cut of the 1926 version of Faust. Additionally, the other three movies--Tartuffe, The Last Laugh, and Nosferatu--carry over the extras from their previous solo releases, though in the case of Last Laugh and Nosferatu condensed to a single disc rather than being spread across two DVDs. (Thus explaining the "Disc 1" that appears on the menu of Nosferatu.) All of these feature the most current restored prints, which have been put together through great care by the Murnau Foundation.

All of the films here date from Murnau's German silent period, from 1921 to 1926, before the director emigrated to Hollywood and began working for 20th Century Fox.

The first film in the set, The Haunted Castle (1921; 81 minutes), is actually Murnau's eighth. Based on a serialized novel by Rudolf Stratz, The Haunted Castle has the feel of a drawing room mystery, though it lacks the peril of a dead body to give it the oomph one might expect.

Subtitled The Exposure of a Secret, the story is set during a holiday at Vogeloed Castle. A group of moneyed aristocrats have gathered to hunt, though dreary weather has trapped them indoors. The vacationers are shocked by the arrival of Count Oetsch (Lothar Mehnert), a scandalous figure who had not been invited to the festivities. The Count has been dogged by rumors that he killed his own brother four years prior, making him persona non grata in polite society. To make matters even more difficult, his widowed sister in law, the Baroness Safferstätt (Olga Tschechowa) is scheduled to arrive at any time, as is the distant relative of her late husband, a pious priest from Rome. The Lord and Lady of the castle fear how their friends will react to seeing the murderous Count, but the gentleman refuses to leave.

Things grow more complicated and suspicion increases when the priest disappears, presumably from inside a locked room. He was in the middle of hearing a confession of the Baroness, one that could finally expose the truth behind the murder of her husband. The rumors of the castle's supernature also play on the minds of the guests. One can see signs of the Murnau to come in the dreams that some of his characters receive in their fitful slumber, particularly in one hunting man's visions of a deformed claw reaching in through his bedroom window.

Yet, beyond that lone eerie effect (for a film that purports to be about a house of spooks, there is very little spookiness to be had), The Haunted Castle shows us a Murnau who is still developing. Most of the shots in the film are static, the straight-ahead framing looking more like a stage play than the living cinema that was just around the corner. The actors move within the camera's range rather than the camera moving around them. Though fairly entertaining, the story of The Haunted Castle is also fairly rudimentary. It doesn't take much to see where it is going or figure out what happened to the missing priest. Though a serviceable B-movie directed with a very assured hand, there was much better material to come from Murnau.

And indeed, that better material was only a year away. What a difference twelve months can take! Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922; 94 mins.) is a whole other kind of cinematic beast. The prototype for virtually all vampire movies to follow, this unauthorized borrowing of the Bram Stoker Dracula novel is a frightful classic. With Max Schreck in the title role--the legend surrounding the performance later recreated by Willem Dafoe in Shadow of the Vampire--Nosferatu achieved a lower temperature of chills than the early movie industry was used to.

The story is likely familiar to anyone who has seen any of the many Stoker adaptations: young real estate agent Hutter (Gustav v. Wangenheim) is sent to a distant land to aid the bizarre Count Orlock (Schreck) in acquiring British property. Failing to heed local folk tales about the scary Nosferatu, Hutter goes to Orlock's castle and is soon trapped in the Count's nocturnal world. Seeing a picture of Hutter's wife, the strikingly beautiful Ellen (Greta Schröder), Orlock heads back to England to take possession of the woman, leaving dead bodies in his wake.

Schreck's amazingly perverse turn as the vampire, which was so believable that many have believed him to be a real creature of the night, is a wonder to behold. Wearing all kinds of prosthetics to elongate his features, giving him jagged teeth and demonic nails, he looks utterly inhuman without any of the cracks showing in the illusion. To see him rise up out of a coffin without aid or the use of his own limbs is a scary movie moment even now. Beyond Schreck's total role immersion, the thing that is most striking about Murnau's Nosferatu is it's all-pervasive atmosphere of terror. The director has created a rarefied world where nothing is as it seems and the scent of fear inches across every frame. He also employed clever and surprisingly convincing special effects to make Count Orlock a creature who is not bound by spatial relationships or time restrictions. Playing with film speeds, double exposure, and other early effects tricks, Murnau practically splits the screen in half, showing us the realm of the undead on one side and the more grounded reality on the other.

In addition to Schreck, Alexander Granach is fantastically mad as Knock, Hutter's boss and Murnau's version of Renfield. I was also quite taken with Greta Schröder, whose Helen comes off as more than a virginal beauty. Her dark hair and eyes give way to hints of a darker interior life, that there is something in this troubled woman that makes her compatible with the bloodsucker. She is not just drawing him in because of her beauty, but because maybe they are more simpatico than anyone realizes.

Two years and three films later, Murnau found himself in a wholly different mood for The Finances of the Grand Duke (1924; 77 mins.), a farcical drama of intrigue and concealed identities. Working from a script by Metropolis-scribe Thea von Harbou, the director creates the fictional island nation of Abacco, a remote paradise run by a kindly dictator (Harry Liedtke) whose pursuit of personal happiness for himself and his people has not lead to the wisest of monetary decisions. The Grand Duke is in debt up to his eyeballs and in danger of losing the whole kingdom to a scheming creditor (Guido Herzfeld) and yet still won't give over to exploiting his people by selling them into sulphur mining.

Salvation seems to lie in the promise of marriage and an influx of money from a beautiful Russian princess (Mady Christians), and Olga's promissory letter becomes a tool for blackmail, stock market manipulation, and even the usurping of power. With both Olga and the Grand Duke traveling in disguise, their way out of this mess is reliant on the man who has bought out the Duke's debt in hopes of cashing in, the smart and not-so-evil capitalist thief, Philipp Collins (Alfred Abel).

The Finances of the Grand Duke is an entertaining but light concoction. Murnau uses the ocean shore and seaside towns for some great panoramic shots and he continues to show a mastery at populating a frame that far exceeds the stiffness of The Haunted Castle, but the script underplays the comedy maybe a tad too much. The plot could have been far more screwball than what we see here, something more akin to the heights of absurdity hinted at in the one tangent where the creditor, Markowitz, inexplicably runs afoul of a couple of "animal impersonators." One man is dressed as a monkey and the other as a lion, and their presence in this brief sequence is hard to explain. It does little to move the story along, as Markowitz is already out of his office on other business, allowing Collins to rob him. Is it a distraction for the character or the audience?

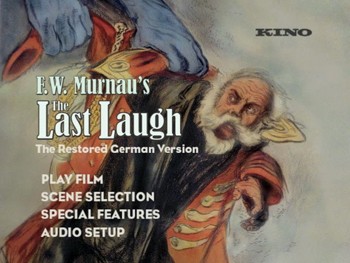

Though set in a contemporary German city, the locale for The Last Laugh (1924; 90 min.) is no less surreal or fantastically imagined than the gothic nightmares of Nosferatu or the fictional kingdom of the Grand Duke. The home of the aging hotel doorman (Emil Jannings) is a malleable one, the skyline of the city, constructed via matte paintings and other special effects, being a reflection of the man's mental landscape. Thus, when life is good, the city looks flashy and futuristic; when the chips are down, the buildings bend and point toward the doorman like an accusing finger.

By contrast, Murnau creates a very real tenement where the man lives, showing the day-to-day lives of the working poor with a clarity of detail that is as stunning as the more ostentatious life at the Atlantic Hotel. The doorman has been working there for many years, looking puffed up in his uniform and his crazy white facial hair. A gregarious fellow, he enjoys the work, and so he is unhappy to be taken off of his post. Fearing that he has grown too old for the position, the hotel management is moving him to be the lavatory attendant, which is where they exile employees before they are sent out to pasture. If that weren't enough, the man's daughter is also getting married, making him equally redundant as a father as he is in his occupation.

This tragic drama follows the inevitable decline of the doorman as this change in life weighs down on him. At first he attempts to hide the demotion from his family, stealing his doorman's uniform back and wearing it home. Once the truth is uncovered, however, the doorman's humiliation is complete. Now a social outcast as well as a professional one, the bathroom becomes like his own personal hell.

Murnau pulls out all the stops for The Last Laugh. In addition to the grand hotel scenes and the near-documentarian footage of the apartment housing, he also shoots much of the movie from the doorman's point of view, including many tricked-out scenes and dream sequences when the old man is drunk. Working from a script by Carl Mayer, The Last Laugh is presented entirely without dialogue-related title cards. Only explanatory cards at the front and back of the film, as well as shots of newspapers and letters, use any words to convey the story. The rest is all told through action. It's brilliant filmmaking, full of pathos, humor, and even scenes of extreme tension, particularly when the doorman is exposed. Emil Jannings pulls off a tremendous performance, the sheer physicality and emotional power akin to Michel Simon's star turn six years later in Renoir's Boudu Saved from Drowning. Jannings manages to take the doorman from affable highs to the lowest of lows with nothing but his body and face to aid him.

The only thing that keeps The Last Laugh from being a perfectly realized tragedy is a studio-imposed happy ending. Presented as a fantasy coda, it shows the doorman stumbling into a fortune after a rich American dies in his bathroom. Realizing the falseness of this ending, Murnau and Mayer comply with the bean-counter's demands by overdoing it, pushing the opulent display of the doorman's new wealth to its most extreme limits. They seem to be saying that if the studio bosses want to see the opulence that the rest of the movie was meant to critique, they would show it in all its unattainable sparkle so that no one would quite believe that an ending of such invention could possibly be sincere.

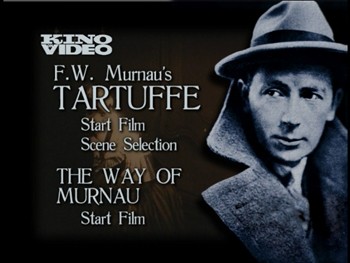

Emil Jannings was teamed with Murnau again a year later, playing the title character in the adaptation of Moliere's Tartuffe (1925; 63 mins.). Surprisingly, this film version of the classic play ends up having quite a bit in common with The Haunted Castle, though admittedly much of that in the new frame Murnau and writer Carl Mayer have concocted. In this set-up, a young actor (Andre Mattoni) discovers that his grandfather (Hemann Picha) is under the sway of his scheming housekeeper (Rosa Valetti), who is cutting the grandson out and getting the old man's fortune for herself. Like Count Oetsch in The Haunted Castle, the grandson here cooks up his own scheme, assuming a false identity in order to plead his case by alternate means. He dresses up as the proprietor of a traveling cinema and stages a screening of Tartuffe in his grandfather's house, hoping that the geezer will see the truth in the tale of the hypocritical priest (Jannings) trying to sway a gullible husband (Werner Krauss) to give up his fortune and betray his loving wife (Lil Dagover). Thus, the maid is Tartuffe, and the grandson is like the loyal woman who will go to any length to expose the plot against her man. (Read whatever Freudian explanation into the gender switch that you want; that's your choice!)

Tartuffe's using religion to alienate the wife from her husband is reminiscent of Oetsch's murdered brother, whose religious piety drove a wedge in his marriage, as well. Lustful temptation was the undoing of the Baroness in Castle, and it is also the downfall of Tartuffe, who is taken in by the wife's advances and her powdered bosom. Murnau gives the play lively movement, traveling up and down the stairs of the fancy home of his victims. Jannings is fittingly grotesque, making Tartuffe a greasy lecher, and Dagover is strangely lovely and virtuous in her role as the wife. With the framing device, Murnau also modernizes the play while suggesting that cinema has just as much power to expose the evil that men do through allegory as the legitimate theatre.

F. W. Murnau finished his German career by returning to the ambitious supernatural tableau of Nosferatu, this time creating Heaven, Hell, and all that lies in between for an adaptation of Goethe's Faust (1926; 106 mins.). The scope of this film is announced right from the get-go, opening as it does with the Horsemen of the Apocalypse and transitioning into a debate between an arcangel (Werner Fuetterer) and a demonic Mephistopheles (Emil Jannings, once again) over man's ability to choose between right and wrong vs. his tendency to do so. To prove that Earth is the realm of the devil, Mephistopheles wagers that he can corrupt the good Dr. Faustus (Gösta Ekman) with temptations of real power. Unleashing a plague on the human populace, Mephistopheles offers Faust the ability to save the poor souls stricken by the ailment, beginning the man's downward slide.

The overall mood of doom and gloom and the tremendously vivid realizations of the various mythical elements of this story are astounding. Jannings is incredible as the devilish creature, poised over Faust's city, his great black wings spread across the sky as he unleashes pestilence on the world with one great, hellacious fart. Watching Murnau's Faust is like seeing an Hieronymous Bosch painting come to life, the worst warnings of medieval religious theatrics given flesh.

Also very good is Ekman as Faust, playing him both as the old doctor and as the rejuvenated young man given a second chance on life through Satanic pact. So good was he as the old man, and so good was his make-up, I didn't realize he was a younger actor playing old until Mephistopheles instigated the change. It's the second prong of temptation. The promise of power quickly turns sour, and though the moral of being careful what you wish for is rather obviously in front of Faust's face, he does not latch onto it. The second offer of youth and a reunion with lost love seals the deal for him. Yet, he quickly grows bored, and it's fitting thematically that when he does, he becomes hopelessly enamored of the virginal Gretchen (Camilla Horn, returning from Tartuffe). It's as if now that he's evil he is compelled to destroy that which is good.

When Faust is seducing Gretchen, aided by his brimstone buddy, Murnau and writer Hans Kyser alleviate all the moral heaviness with a fun bit of comedy. Gretchen's unattractive older aunt (Yvette Guilbert) takes a liking to Mephistopheles, and she chases him the way Pepe Le Pew chases a striped cat--and he runs from her just as vigorously.

Naturally, the odds are against Faust, especially with the way the deceitful Mephistopheles keeps piling obstacles up around him, and the man will have to struggle for his redemption. The "all you need is love" message that comes in the end is a tad obvious, but since Murnau returns us to the spiritual plane to deliver it, he covers up the easy allegory with cinematic excitement. It's a marvelous ending, the grandest of finales, both to Faust and to the German stage of the legendary director's career.

(left to right: The Finances of the Grand Duke; The Haunted Castle)

THE DVD

Video:

The movies in the Murnau boxed set are all meticulously restored. The prints are presented in the original 1.33:1 aspect ratio with a tinted image that changes colors across scenes without being glaringly obvious (though The Last Laugh and Faust are entirely in black-and-white, no tint). Given the age of these movies and the lack of care given to them over the years, the efforts made to bring them back into circulation appear Herculean in their grandeur. Sure, there is still the occasional hint of wear and tear or a jerky edit somewhere during most of them, but these hiccups are by far the exception and not the norm. To even note them seems unkind, given how good all of these movies look. The only film with pervasive noise on the picture is Tartuffe, which has a lot of scratches and surface spotting, but an essentially clear picture underneath. Faust is a close second in this regard; additionally, unlike the others, Faust is pictureboxed, meaning there will be lines on all four sides of the image when viewed on a widescreen monitor.

Though the restored prints can border on the immaculate, they are not always digitally rendered in as conscientious a fashion. Unfortunately, the discs don't appear to be deinterlaced, and so you can expect to see combing throughout. This is particularly noticeable in the films with more action shots, such as Nosferatu and Faust. For a full comparison of other editions of Nosferatu, read John Sinnott's detailed assessment here. It should also be noted that The Last Laugh features a print restored in 2003, and this DVD is different than the Kino release from 2001, also reviewed by John Sinnott here.

Sound:

For a lot of these films, there was no original score or that material was lost, and so new musical accompaniment was created for these releases or sometimes for recent touring prints: The Haunted Castle has a score by Neil Brandt; The Finances of the Grand Duke by Ekkehard Wölk; a piano score by Javier Perez de Azpeitia for Tartuffe. These are all given mono mixes that sound very good, with crisp audio rendering and no distortion.

In cases where possible, the original scores were also reconstructed and given new recordings and state-of-the-art audio mixes. Thus, for Nosferatu, the vintage music composed by Hans Erdmann has been put together for a fresh presentation, as has Giuseppe Becce's 1934 accompaniment for The Last Laugh. In both cases, Kino has created two amazing audio mixes for the films: 5.1 Stereo Surround and 2.0 Stereo.

Faust has two audio options. First, the 5.1/2.0 treatment is given to a new recording by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra working from materials "compiled from historic photoplay music." I enjoyed this soundtrack. It was full of the proper bombast and intense emotions fitting the images. For a more subdued option, though, you can also listen to a piano version of the original 1926 orchestration performed by Perez de Azpeita, who also did the music for Tartuffe.

The intertitles in the movies are all clean and readable, newly created for these DVDs from the most accurate source reference available. In the case of Faust, the titles are in their original German form, which is a nice choice because they are rather artfully done and fit the tone of the picture. English subtitles are provided.

Each of these movies begins, actually, with an explanation of what materials were used for both the image restoration and the intertitles restoration.

Extras:

The Murnau set is packaged in a standard side-loading box. Each film is housed in a thin plastic case, making for a compact collection easily stored on standard DVD shelves. Each movie also comes with its own set of extras.

The Haunted Castle has three supplemental features: excerpts from the original Rudolf Stratz novel, a gallery of set design paintings by Robert Herlth [pictured above], and an image gallery of stills and promo images from the movie.

Nosferatu is one of the movies in the set that has been distilled down from a two-disc package to a one-disc version, though without losing any of the extras. This is because the second disc in the previous edition was a second version of the movie with the original German intertitles; that version is not available here. The extras that are available are as follows:

* "The Language of Shadows: The Early Years and Nosferatu," a 52-minute featurette looking at Murnau's early career and the history of one of his most famous films. In addition to examining how the film came together, the featurette also talks about its impact and the turns the future took for some of the participants.

* A 3-minute piece on the digital restoration of the movie.

* Excerpts from eight of Murnau's other German films, many of which are also included in this set in their entirety.

* Photo gallery.

* Scene comparison showing the journey from Bram Stoker's Dracula novel to Henrik Galeen's screenplay to the finished film.

The Finances of the Grand Duke has an audio commentary by film historian David Kalat. The commentary is incredibly thorough, covering the production of the specific movie and the origins of the story, Murnau's greater career and collaborators (including future director Edgar Ullmer and Thea von Harbou), a discussion of style, challenges of restoring silent films, and also Murnau's personal life.

The Last Laugh has a 40-minute documentary called "The Making of The Last Laugh," the original German title sequences, and an image gallery. Another documentary on Murnau himself appears on Tartuffe, in the form of the 35-minute German production "The Way to Murnau," directed by Alexander Bohr in 2003. This is put together with reminiscences from those who knew Murnau and clips from his movies.

Faust finishes out the set with a healthy dose of bonus materials, including:

* two galleries: a selection of photos and a look at Robert Herlth's set designs.

* Notes on how the Mont Alto score was compiled.

* A critical essay by film historian Jan Christopher Horak.

* Screen test footage from Ernst Lubitsch's never-completed 1923 version of Marguerite and Faust. Commissioned by Mary Pickford, this would have been Lubitsch's first American film had Pickford not called it off. The tests clock in at just under 12 minutes, and feature multiple actors--Francis McDonald, Lestor Cuneo, and Lew Cody among them--trying out for Mephistopheles. An interesting curiosity, though a bit repetitive.

FINAL THOUGHTS:

Highly Recommended. F.W. Murnau was a creatively ambitious, innovative filmmaker. This six-movie set from Kino, Murnau, covers his career in German silent cinema, from the drawing room mystery of The Haunted Castle through the powerful and effects-laden Faust. There are a variety of tastes here, going beyond the usual conception of Murnau as merely a teller of scary stories. There is comedy, adventure, and in The Last Laugh, very real tragedy and social critique. Across the films, we see the filmmaker grow and invent as he entertains, making this a pretty essential collection for cinema fans.

(Nosferatu; The Last Laugh)

Jamie S. Rich is a novelist and comic book writer. He is best known for his collaborations with Joelle Jones, including the hardboiled crime comic book You Have Killed Me, the challenging romance 12 Reasons Why I Love Her, and the 2007 prose novel Have You Seen the Horizon Lately?, for which Jones did the cover. All three were published by Oni Press. His most recent projects include the futuristic romance A Boy and a Girl with Natalie Nourigat; Archer Coe and the Thousand Natural Shocks, a loopy crime tale drawn by Dan Christensen; and the horror miniseries Madame Frankenstein, a collaboration with Megan Levens. Follow Rich's blog at Confessions123.com.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||