| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Trip to the Moon Restored (Limited Edition, Steelbook), A

Please Note: The screen captures used here are taken from the DVD version included in the set, not the Blu-ray edition under review.

A cinematic event years in the making, the 2010 restoration of Georges Méliès's technically pioneering, thematically prescient, eternally charming 1902 film A Trip to the Moon (Le Voyage dans la Lune) represents, for the contemporary movie lover, a return to innocence of near-mythic proportions. The film's reputation as a masterwork that immeasurably advanced the art and technology of cinema had long been more than adequately supported by black-and-white prints that survived and circulated over the decades, but in 1993, an original hand-colored reel of the film turned up, reminding the world once again that the idea of and longing for color in film long predated the technology that would make it feasible for movies to be shot in color. The intrepid restorers of A Trip to the Moon had to wait, in their own turn, the better part of two decades for digital technology to catch up to their vision of a newly restored version that would let audiences of today to see it as it would have looked in a Parisian salle de cinéma in 1902. But that dream has now come true, and several generations' worth of a not-quite-accurate impression of the film can be washed away as this miraculous achievement in film restoration takes us back, allowing us to be present - as present, at least, as anyone has been in many, many years - at the glorious birth of what would become the definitive art form of the 20th century.

To categorize A Trip to the Moon as "science fiction," especially at this green screen/CGI point in moviemaking, would be both reductive and misleading. It is true, though, that the film's story deals with very futuristic, far-out speculation on space travel, depicting a master astronomer/professor who convinces even his naysaying colleagues that a rocket trip to the moon is a viable possibility, and one he can turn into a reality. After overseeing the construction of said rocket, the professor and his fellow scientists take off, landing on the moon; soon thereafter, they experience a surface snowstorm that drives them beneath the lunar surface. There, they encounter a world of bizarre half-human, half-reptile creatures who, after the earthlings put up a brave fight, capture them and present them to their lobster-clawed king. Our brave head astronomer/ringleader defeats the king, and after the scientists make a daring escape back to their rocket, they sail off a moon cliff (carrying with them an especially persistent moon monster who grabs onto the rocket's tail), land safely in ocean waters, and are brought back to civilization so that they may be feted for their successful mission by a crowd of admirers as their living, breathing, crazily dancing specimen of moon life is paraded for all to marvel at. A statue depicting the brilliant astronomer as "science" embodied is erected at the center of a perpetual celebration.

But even though it would be over 60 years before Andrew Sarris definitively articulated that it's not what the story of a film is but how that story is told that truly defines the experience, it's as true here as it is everywhere else, and the mere presence of scientists, spaceships, and extraterrestrials does not necessarily a precursor to 2001, Star Wars, or Alien make. For one thing, it's hard to imagine a film with a more cheerfully nonchalant, heedless disregard for all tenets of reality, rationality, or logic (let alone science); Méliès creates an entire parallel world in which the rules of gravity, perspective, distance, and time are completely elastic and can be altered at a whim. The fact that the big launch and moon landing are facilitated by comely young women wearing what appears to be "futuristic" swimwear; that the rocket lands with a splat in the eye of an anthropomorphized, curmudgeonly moon; that the professorial space travelers carry umbrellas with which they combat the moon monsters in their underground kingdom of giant mushrooms, causing them to go up in a satisfying *poof* of gaudy smoke with each direct hit; and that the film pauses for an interlude (or dream sequence) in which adorable, sly star fairies morph into celestial entities that beckon down the snow that awakens the slumbering explorers - all of this would seem to place A Trip to the Moon less in the sci-fi pantheon and more into a lineage deriving from storybooks, the constantly surprising and amusing world of Lewis Carroll, and stage-magic showmanship (magician having been Méliès's vocation before he realized that celluloid was an even better outlet for his visual sleight of hand), with Bunuelian surrealism and the invented-from-scratch worlds of Expressionism as its successors. (Not to mention the minutely detailed, externalized-whimsy quality that marks the films of Wes Anderson; every choice of costume, set design, and mise-en-scène in A Trip to the Moon has been made for reasons infinitely more aesthetic than practical or even remotely "accurate," technologically speaking.) What makes the film's special effects so memorably, uniquely special is not in any way how "realistic" they are; unlike the apparent realism-beholden raison d'être of much of our contemporary movie magic, the look and feel of the spaceship, the lunar surface, the observatory, and the moon monster's kingdom are striking for their beauty, originality, and dream-like internal logic, not their resemblance to anything that actually exists.

That's where the recovery of the film's original hand coloring makes the biggest difference. One can certainly think of later films (Michael Curtiz's 1938 The Adventures of Robin Hood springs most readily to mind) that attain an enrapturing storybook quality through Technicolor, but the hand-painted colors here are something else, something artisanal and slightly unpredictable, something more one-of-a-kind (as each print was, by necessity, colored individually). The colors are bold, sometimes primary (red tones figure prominently; I always thought that the fluid that erupted when the rocket ruptured Mr. Moon was some kind of cream cheese, since that's what the moon is made of, but it turns out it's more likely blood) and sometimes delicate pastels, as in the light greens and pinks worn by the parade of women scientific assistants/secretaries. The fact that this vitally important component of the film's sensibility is once again a part of it is cause for rejoicing.

On the visual level, then, the restoration is irreproachable, truly a thing of beauty. What's bound to cause more head-scratching or controversy is the new soundtrack that the restorers commissioned for the re-release, with music by the French electro-pop group Air. The duo do have strong credentials when it comes to providing the soundscape for visually lush, evocative images in the form of their score for Sofia Coppola's The Virgin Suicides, which demonstrated that their sensibility can dovetail nicely with that of the right filmmaker. The sounds they've provided here - percussive marches, analogue synthesizers, and twangy/psychedelic guitars making sweet, slightly melancholy melodies - seem to me quite apt and rather nicely done. If the pop-rock sound is somewhat jarringly "modern" for a film of A Trip to the Moon's vintage, I don't believe that detracts from the experience; as quaint as it may look after 110 years, jarringly modern is what the film is all about, artistically (and even technologically, in a certain fanciful sense) speaking. Nor does it violate any aesthetic code; silent films have no "original" soundtrack and were meant to accommodate any musical or verbal sonic accompaniment that any reasonably tuned-in exhibitor saw fit to provide, so purism on that count seems untenable. (One minor criticism: It would have been nice, perhaps - and definitely possible - to offer other, more traditional audio options on the main presentation, as is done for the B&W version of the film included as a supplement, for those who might demur from my liberal assessment.)

No less than the ringleader of the movie lovers, Martin Scorsese, recently used huge studio money and the up-to-the-minute appeal of 3D to make Hugo, a feature-length love letter to Méliès and A Trip to the Moon; in that film, two children were bowled over by the sheer pleasure and wonder to which Méliès dedicated his considerable skill, ingenuity, and inventiveness. Now, this lovingly rescued, definitively restored edition of Méliès's greatest work offers that experience of guileless enjoyment to anyone, of any age, available at our fingertips whenever we want it - a futuristic fantasy that even Méliès wouldn't have dared conjure, and one that the heroic team behind the restoration have made come true. The amount of effort that went into the original creation of the film and into the prolonged process that has resulted in its remarkable rejuvenation is clear from the strange gorgeousness of Méliès's spectacle and the principled, exacting precision with which it's been restored, but there isn't a moment that seems calculated or anything but as effortless as something can only be when it's going where nobody has gone before, letting pure imagination flow and channeling it through the language of a new art form, one that's being invented as they go. Far too much in our culture that promises a return to a wide-eyed, hopeful, childlike state of wonder is cynical, hollow, or reactionary, but not A Trip to the Moon (especially as it's presented here, with more of its original magic intact than was previously thought possible). When it comes to tapping us back into the simplest, purest pleasures of cinema, it's the real deal.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

It would be bizarre to see an 110-year-old film without any trace of flicker, scratch, and other signs of wear, and all of that is certainly present here. But in the context of its age and the alarming delicacy of the materials that were used in making prints of films in the cinema's earlier days, the shimmering beauty of this A Trip to the Moon--AVC/MPEG-4 encoded, 1080/24p-mastered, and presented at its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1--is scarcely short of miraculous.

Sound:A Trip to the Moon's new soundtrack by Air is presented in a room-filling DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround soundtrack that is rich, deep, clear, and sparkling, as is The Extraordinary Voyage documentary; all the other extras are presented in an uncompressed PCM 2.0 soundtrack. It all sounds tremendously fine, with no complaints whatsoever from the audiophile POV.

A Trip to the Moon is housed in deluxe collector's-edition packaging - a sturdy, beautiful, and well-designed metal snap-case that also contains a standard-definition DVD version repeating the entire program - and is packed with extras that easily justify what might seem a steep retail price for a 12-minute short, however indispensable it may be. These include:

--The big extra here is the 65-minute documentary The Extraordinary Voyage (Le Voyage extraordinaire), made in conjunction with the release of the new restoration and directed by Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange, proprietors of Lobster Films (the French firm that, in cooperation with a worldwide team of collaborators, is responsible for this edition of A Trip to the Moon). Bromberg (who narrates in English) and Lange give us the whole story, going all the way back to Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and the sci-fi craze of the later 19th century before catching up to the turn of the (20th) century with a reminiscence on the birth of cinema, ultimately narrowing in for a mini-bio of Méliès. They offer a brief education - with many archival photos, clippings, even audio of Méliès himself - on how the most whimsical of the cinematic forefathers transitioned from stage-based showmanship to cinema after being inspired by the technologically-pioneering Lumière brothers, as well as an expansive rundown of his career, including his ultimate commercial failure; his humiliating forced re-entry into the petit bourgeoisie; and his eventual revival and rightful acclamation by a burgeoning strain of enthusiasts who would come to be known as cinéphiles. (Those who loved Hugo will find it interesting to pinpoint where Scorsese's film bows to historical accuracy, and may be surprised to learn how often that actually was.) Bromberg and Lange also call upon latter-day devotees of Méliès--including directors Jean-Pierre Jeunet (Amélie), Michel Gondry (The Science of Sleep), and Michel Hazanavicius (The Artist); Missing director/Cinémathèque Française president Costa-Gavras; and Tom Hanks (seen in archival material from the set of his TV mini-series From the Earth to the Moon) to pay their respects.

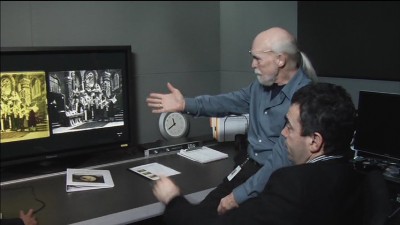

The second half or so of the documentary is dedicated to the restoration process, and it's essential viewing for anyone interested in seeing what, specifically, is involved in this painstaking process of cultural preservation. There are side-by-side contrasts/restoration comparisons galore; more importantly, film restoration is explored and explained in much more detail than I have ever seen before, and one even imagines that seeing the fascinating work processes captured here, which must be incredibly fulfilling for its practitioners, could well inspire some younger viewers to want to become a film preservationist/restorer when they grow up. Lange, Tom Burton of Technicolor, and their vast teams of patient, expert technicians are on hand to tell the story of how the sheer luck of finding usable source materials, securing international financial/logistical participation, and a lot of ridiculously difficult, meticulous, infinitesimally precise work came together to make this restoration project the success that it is.

Watching A Trip to the Moon will leave you well primed for all the backstory provided by this remarkably thoroughgoing behind-the-scenes. (The main short film and the documentary together add up to about the length of a short feature, so watching them back-to-back works out nicely.)

--Interview with Air (12 min.), in which the beloved French electronic-pop group lounge in their studio and discuss their aim of creating a sound for the film that was neither "retro" or "trendy" but an organic, artisanal part of the whole, which led them to approach scoring A Trip to the Moon as if they were a member of the original team, subservient to the moods and needs of the film alone. They also mention how seeing Méliès's work restored to its original coloring keyed them in to how he was, in his time, as much a youthful spinner of pop culture as they are, with the colors and surrealism of the film reminding them of the Sgt. Pepper sleeve.

--Two additional astronomer-centric Méliès shorts (both in black-and-white): The Astronomer's Dream (La Lune à un mètre) (1898, 3 min.) (I think a better translation would be The Moon Up Close) is a sort of precursor to A Trip to the Moon, using the pretext of an astronomer having a nightmare to pack as much madcap action as possible into the short running time, including a voracious moon that takes "a trip to the Earth," looming in the astronomer's window and causing mayhem that Méliès resorts to all kinds of amusing visual trickery to convey. The Eclipse: The Courtship of the Sun and Moon (Eclipse de soleil en pleine lune) (1907, 9 min.) shows Méliès's wit and originality wearing thin, but it's still not without its charms, basically reprising the opening of A Trip to the Moon, with an excited astronomer announcing an upcoming eclipse to a seemingly credulous group of colleagues. We glimpse, through their telescopes, the amorous convergence of the anthropomorphized sun and moon, followed by other surreal, loosely associated but very pretty bits of sky pageantry before the film literally tumbles back down to earth for its slapstick finale.

--The black and white version of A Trip to the Moon with which we were all so familiar before being blessed by Lobster Films, The Technicolor Foundation, and Flicker Alley with the new color restoration. It looks just fine (very well restored in its own right), and some viewers may actually prefer the three more traditional audio options available on this versions (including one with straight-piano score by Frederick Hodges, pastiching Offenbach, Débussy, and Saint-Saens, among others; one with score by Robert Isreal accompanied by voice-over narration written by Méliès*; and one with the Hodges score and voice actors performing the parts, based on the manner in which voice-overs were performed during some early U.S. screenings of the film - all of which are known to have accompanied A Trip to the Moon at one time or another in its earlier runs) to the decidedly more modern-sounding new score by Air on the main, completely restored version.

--A 25-page booklet including all the details of the original film and this new release; stills from the film, Méliés drawings, and archival photos; and an essay excerpted from the book A Trip to the Moon Back In Color by Gilles Duval and Séverine Wemaere.

*Flicker Alley has brought it to our attention that initial runs of this edition are missing the narration; the error will be corrected, and those who find they have purchased a version containing the defect will have their disc replaced free of charge simply by requesting the replacement at Flicker Alley's website.

It's not quite as dramatic an 180-degree shift as when Dorothy emerges from her black-and-white Kansan cabin into the Technicolor land of Oz (even in the black-and-white form in which most living film lovers have seen it, Méliès's masterpiece has remained captivating) but the restoration of A Trip to the Moon to its original hand coloring really does add a dimension that leave the now second-tier black and white versions looking a bit pale by comparison, if not obsolete. This new, definitively restored version (which constitutes a vital, internationally-cooperative act of film preservation), lets the film's full brilliance fall entirely into place; the colorfulness seems so natural and fitting, like it always should have been there. The film is not only an important landmark in the history of cinema, but unlike some other venerated films of equal importance from those first, silent, pioneering phases of cinema (Birth of a Nation, say, or Battleship Potemkin), it has a lightness to it, a simplicity and a propelling sense of pure joy that makes its appeal instantaneous and universal. Rounded out as it is with thoughtfully conceived and created packaging worthy of its stature and a bounty of contextualizing extras that draw us further into and behind the Méliès magic, this Blu-ray edition of A Trip to the Moon deserves the highest honors that can be bestowed in any given situation, which in this case means it easily earns DVD Talk Collector Series status.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||