| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Sunday Bloody Sunday: The Criterion Collection

Please Note: The images used here are taken from promotional materials and stills provided by The Criterion Collection, not the Blu-ray edition under review.

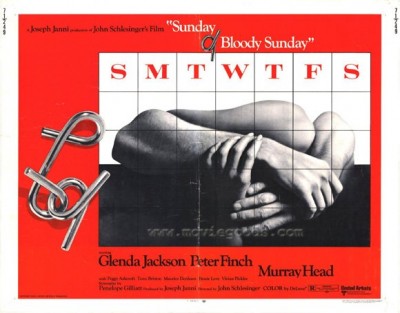

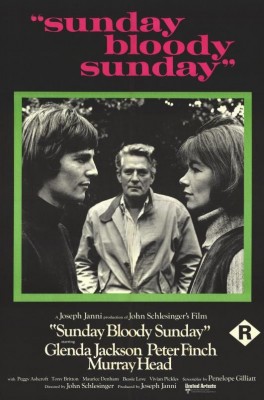

John Schlesinger's followup to his acclaimed hit Midnight Cowboy (1969), though it didn't win the Oscars and still isn't as widely known or venerated as its predecessor, still stands as his best, most personal, most indelible film. I'm talking, of course, about 1971's Sunday Bloody Sunday, Schlesinger and screenwriter Penelope Gilliatt's story of an intense, ill-fated love triangle against the backdrop of a London that, sobering up from flower power and grooviness, is no longer swinging so much as having a long, fraught, self-analytical and self-reflective think amid widespread unemployment and the impending general "malaise" that still characterizes the '70s in the popular imagination. That malaise was accompanied, however, by increasingly curious, bold, and fine-tuned ideas and practices on the front lines of the sexual revolution (it was also, fortunately and unforgettably, the decade of feminism and gay rights), and that's where our two protagonists -- Alex (Glenda Jackson), a smart upper-middle-class divorcée trying her best to reject the stuffy materialism and dutiful marriage of her parents' generation, and Daniel (Peter Finch, Network), a successful gay, Jewish doctor -- find themselves, it would seem not entirely prepared, as they both knowingly share the affections of an idealistic young artist (Murray Head) who, wholly free of "hangups," sincerely cannot understand a single possessive feeling either of his lovers have, or how the ease with which he transitions from one to the other, always leaving one of them alone and pining, hurts them. What can possibly come of such a love triangle, when the apex can afford such a lofty, carefree, invulnerable idealism while the two bases, who share his ideals (or want to) but are much more vulnerable, struggle but fail to avoid the sins of jealousy, possessiveness, and compulsory monogamy proscribed by the high-minded paramour they awkwardly share?

The film's timeframe of a week gives Schlesinger and Gilliatt ample time to finely comb through and touch upon the many fibers of which each of the lead characters (the film really does belong primarily to Jackson and Finch; Head, an appealing presence, is more of a cipher) are comprised; this is the kind of movie, of which a nice handful were to be made during the ensuing final-cinematic-Golden-Age decade, that cares most passionately about letting its characters live and breathe, never forcing them into obvious patterns or shorthanding them unnecessarily in order to move the plot along. The film is thus a loose-feeling, highly naturalistic, but careful process of getting to know, feel for, and understand very well Alex and Daniel, their internal and external difficulties with even defining what happiness is to them, let alone attaining it. We take our time getting to know them -- Alex, with her chicly squalorous quasi-bohemian flat and her harried, bemused "aunt" relationship to the brood being raised under her married professor friends' almost comical liberalism (this is a house where the small children know where the pot is kept, and how to use it); and Daniel, practicing out of a home office where he interacts with his often difficult, high-strung patients, providing them all the reassurance and tough love they need. (Alex provides oddly similar moral support to the high-salary clients she must coddle at the posh employment firm from which she's been trying to resign for a very long time, prevented mainly by her trouble composing a letter that adequately expresses her need to move on.) Alex has a much too quietly polite dinner with her parents in their unbelievably stuffy, palatial flat, where she receives an unwelcome, well-meant lecture from her mother and love and marriage; Daniel plays his opera records (the famous trio from Cosi fan tutte plays a prominent role on the soundtrack), attends a nephew's bar mitzvah and shows up dutifully for Saturday services with his close-knit family (perhaps too close-knit; he's unconflicted about being gay, but his family doesn't know, and the matchmaking and marriage pressure are constant) at their synagogue. Vivid, handheld-shot flashbacks take us back to Daniel's own bar mitzvah with its solemn, heavy sense of duty and tradition that lives on in Daniel but is blessedly foreign to his young, handsome lover; and to Alex's childhood horror of her father leaving for work during wartime without his gas mask while air-raid sirens blared and German planes loomed over London.

Then there's what binds Alex and Daniel so close they refer to each other by their first names, though they don't meet or even lay eyes on each other until a very moving, restrained moment near the film's end. They both use the same answering service, their mutual connection to the elusive Bob (Head). This long-haired young artist, with whom they're both head over heels in love and whose "kinetic sculpture" graces Daniel's lawn, has agreed this week both to house/dog/babysit with the pot-smoking children with Alex and to accompany Daniel on a long-planned, much-delayed trip to Italy at the end of the month. As Bob goes back and forth between them, these grown professionals are reduced to behaving like teenagers, anxiously waiting by the phone, stood up, obsessively checking the answering service, trying to maintain the equilibrium and composure required by their lover but inevitably becoming emotionally high-strung and then made to feel foolish about it by Bob, who has the moral certainty only the very young can ever lay claim to (and perhaps the older two are foolish, after all, but this is not a film to moralize or judge; if it has any "moral" at all, it's to let those who have never been foolish in love cast the first stone). Playing house is a mixed blessing for Alex and Bob; he can't take the tedious oppression of even very temporary hearth and home, ducking out for visits with Daniel for which he has Alex's standing, reluctant permission; a party at which Daniel's middle-aged, drunken, upper-middle class, chattering-class friends reveals the worst, most tiresome, and so he flees back to Alex. This is a situation that is being brought to a head, and it cannot go on forever; though it looms large in every waking thought and action of the doctor and the divorcée, the transience of what are in effect two one-sided loves doesn't preoccupy Bob much, as America beckons him to corporate-bequeathed artistic success that both Daniel and Alex know will mean they'll be left behind for good, despite Bob's unwillingness to admit any such finality or permanence either with or apart from his lovers. The situation's dramatic conflict is volatile, but it plays out without contrived scenes/confrontations and with a rare understanding that, while sometimes mordant and always open-eyed and skeptical, is expansive, encompassing all the accruing bits of trauma to which Alex and Daniel are willing to subject themselves as well as their joy, their real love for the loveable-despite-everything Bob, that explains what might otherwise seem their masochism.

The film does offer a refreshingly candid, unflappable depiction of homosexuality for which it has rightly been acknowledged as brave and innovative, but it's far from an issue film; it rationally and warmly accepts, with a grown-upness rare for the time (and too rare still), that some people are gay, some are not, some swing either way, and simply goes with that without making a fuss. The naturalness with which Schlesinger and co. embraces Daniel and Bob's love affair is simply par for the film's well-advised, comfortably moseying but never aimless aesthetic course (redolent in some significant ways of Robert Altman, perhaps the most exemplary ringleader of the '70s' intelligently mellow, less-emphatic, open-eyed and -eared and -minded cinema), in which Schlesinger, production designer Luciana Arrighi, editor Richard Marden, and, especially, director of photography Billy Williams (Women in Love) use composed shots, natural-looking light, measured, relaxed pacing, and carefully realistic mise-en-scène for an immediate, lived-in look, feel, and tone. The connoisseurship and slight fastidiousness of Daniel is present in both his dress and the hardwood floors and artworks in his home/office; the undone dishes and cigarette butts of Alex's apartment, combined with the way it's shot, make it almost possible to smell and touch its homey unkemptness. You can feel the cold of a London morning in the same cheap-ish flat after the fire has gone out in the hearth; you can sense the damp and chill constantly in the air, feel the blustery London wind; even an idyllic day in the park includes mud and traffic, too. The performers are equally up to their own vital, taxing part in maintaining the film's naturalism; the down-to-earth physical and expressive beauty of Jackson, Finch, and Head dovetail very effectively with the film's on-the-fly, down-to-earth feel and the clear-eyed, autumnal, dreary-yet-cozy world its images create and present.

By the end, we feel we have truly lived this week with these "ordinary," neurotic, familiar, yet nonetheless unceasingly interesting characters, the down-tempo and up-tempo moments, the highs and lows both, right up through to the ending that, because we've seen and felt what's at stake for each, is so quietly but deeply heartbreaking. But the film's acceptance of the inevitability of pain in love, sometimes to the breaking point, doesn't feel pessimistic; its final moments are unexpectedly uplifting, freeing. They offer neither the false hope that people like Alex and Daniel can miraculously hang onto the vitalizing but fleeting affections of the free spirits with whom they're in love but wouldn't want to (and couldn't at any rate) cage, nor even the far-fetched idea that they could truly overcome what is perhaps a natural or too deeply ingrained need to pin down and hold onto love when they find it, whatever suffering that instinct causes. What it does convince us of is something more simple, true, and real -- that these people, unlike just anyone, know for certain that it's better to have loved and lost. They can rest secure, at least, in the knowledge that they have been capable of love and will, most likely, love again. And, because this is a film of particular narrative, technical, aesthetic, and performative virtuosity, with an exhilarating ease and generosity in allowing us to get close to and understand its people, we can also bask in that bittersweet knowledge for a good, long moment; we, too, are finally left in the rueful, rather bereft, but somehow refreshed, newly aware, and forward-looking state of mind and heart in which we leave them.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

The AVC/MPEG-4, 1080p transfer -- preserving the original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.66:1 -- that Criterion has created is absolutely marvelous. As an owner of the previous MGM DVD version, I can unequivocally attest to the vast superiority of the picture quality on this edition. The often near-documentary-like immediacy of DP Billy Williams's use of color and light has been restored to its true beauty; its qualities are fine, and while the previous MGM DVD edition ran fairly roughshod over those subtler, richer aspects of the film's naturalistic feel, all the dim scenes are very well-variegated here, the darks solid, skin tones natural, and the grey, rainy London days and slick, traffic-lit nights are vivid, with no aliasing, edge enhancement, or other compression artifacts. The "look" of the film depends more than usual on the grain/texture of the celluloid image, and I'm happy to report very little, if any, overuse of DNR; every frame looks like a movie. In short, watching Sunday Bloody Sunday on this Criterion Blu-ray is as close as you're going to get outside a cinema to seeing it as it truly is meant to look.

Sound:The PCM 1.0 monaural soundtrack preserves the film's original mono sound -- which includes, in the source, some rather softly-mixed dialogue, so you may want to turn up the volume a bit -- wonderfully, with absolutely no crackle, hiss, pops, or distortion to mar its surprisingly many layers, all rich, clear, and resonant here as they make their way from the disc through your speakers.

Extras:--Interviews with cast and crew, including three pieces (approx. 10 minutes each), featuring, respectively, actor Murray Head, director of photography Billy Williams, and production designer Luciana Arrighi, and an audio track (approx. 15 minutes, accompanied by many stills of Schlesinger at work) from a lecture given by the director at the American Film Institute in the mid-'70s. Each of these is revealing to a very worthwhile extent about the art-making of cinema in general and about the way Schlesinger did it in particular, together constituting a truly privileged and in-depth look into many aspects of making Sunday Bloody Sunday.

--An interview with Schlesinger's partner, Michael Childers, with Childers recounting how he and Schlesinger met, got to know each other, and collaborated during the course of their relationship and work, with the main focus being on Childers's recollections of preparing and shooting Sunday Bloody Sunday, including his own involvement and contributions (he took stills and designed some of the posters).

--A 20-minute interview with Schlesinger biographer William J. Mann (also author of Behind the Screen, an informative history of gays and lesbians in Hollywood), who offers a broader and more objective (though scarcely less detailed) view than the interviewees of the place Sunday Bloody Sunday occupied in Schlesinger's life and in his filmography, as well as the many ins, outs, ups, and downs of its writing, casting, preparation, and shooting, with Schlesinger butting heads with screenwriter Gilliatt (who, in her other role as a film critic, had often savaged his prior films) and inexperienced actor Head, but finally surmounting the struggles and meeting the challenges to bring forth his most personal and probably greatest film.

--The film's original theatrical trailer, with its somber narration and outrageously hyperbolic pull quotes, is a sort of fascinating promotional relic. It does represents the film well enough (it is an important film, after all), and it also reminds you just how very, very seriously it was taken by critics, some of whom seem to have beaten the bushes for their superlatives. (Not that I blame them, though much as I love the film, I probably wouldn't stick my neck so far out as to call it "the best thing I've ever seen"!)

--A 30-page booklet featuring an appreciation of the film by Schlesinger friend/New York Review of Books essayist-critic Ian Buruma and a reprint of the introduction to the published screenplay by screenwriter Penelope Gilliatt. (I also must add that Criterion have topped themselves with the package design for this release, modeled after "The Modern Library" book cover designs from approximately the same '70s period as the film; The Modern Library is to literature what Criterion is to film, collecting "important classic and contemporary" works under one imprint, so this design is not only perfect for the film but also has an ingenious broader relevance to The Criterion Collection itself.)

A complex, generous, sad, and tender post-hippie romance, John Schlesinger's Sunday Bloody Sunday was incredibly progressive for its time, but in depicting a love triangle between a divorced woman (Glenda Jackson), a middle-aged gay doctor (Peter Finch), and the young, bisexual free spirit with whom both are in love (Murray Head), naturalism (with a few forays into Fellini-esque memory-dream) is the name of this film's game, both in the performances and the visuals. The means that, despite being specific and open about its turn-of-the-'60s London milieu, it has an undated, even timeless feel to it; if it's quietly revolutionary in its unusually (for then) unsqueamish depiction of polyamory and same-sex romance, it cuts to the real, pertinent heart of the matter with its loose, inquisitive, patient openness to the forever irresoluble problems, joys, pains, and compromises of love and romance. The film is invigoratingly shot in a natural-lit, ordinary-blustery-London-day style (all the better to convince us of the romantic/erotic ray of light the younger man is shining into the lonely lives of his middle-aged lovers), but there's something approaching tragedy lurking in this mundane everyday life, with the two besotted, wannabe-liberal elders struggling to accept, in their own lived experience, the terms of sexual revolution and free love with which they have been confronted by the well-meaning, only unintentionally glib young man whose love they try, and ultimately fail, to share without jealousy or other "hangups" that might drive his effortlessly, maddeningly bohemian heart away. This is a tale of adventure and disappointment in love that takes place at a very uneasy time much like ours, with fairly dire economic uncertainty and the threat/hope of cultural, social, and political sea changes in the air; for all that, however (and for all its rueful acknowledgment of the potential downsides and limits of idealistic flower-power liberation when it meets messy human emotion), it's a film insistent to right up to its "unhappy" ending about the necessity and goodness of romantic love, whatever its unavoidable pitfalls. Its wised-up acknowledgment of the probable impossibility of any perfect, smooth, untainted love doesn't temper its defiance on that count; if anything, Sunday Bloody Sunday is a celebration of falling in love that, with its genuine eagerness (and ability) to give us very sensitively and thoughtfully drawn, recognizably complicated/flawed individuals and its sincere curiosity about how well their best efforts can allow them to truly share themselves with one another, better earns its praise of love than virtually any other cinematic romance you can think of. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||