| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Khodorkovsky

The Russian oil magnate Mikhail Khodorkovsky was once named "the richest man under 40 in the world," but as of 2012, his fate seems rather out of time for what we think of as modern, post-Soviet Russia: he resides in solitary confinement in Siberia after being convicted on convoluted charges of massive theft and corruption (with an ongoing, government-propagated smear about him allegedly putting out hits on some public figures who stood in his way). Many Russians despise him as exemplary of the robber-baron class that exploited the abrupt (if not hasty) switch from Iron-Curtain communism to global-village capitalism; these opportunists swooped in with great greed and speed just as soon as they could, snatching up Russia's now-privatized assets while unethically colluding with the government to manipulate and exclude exactly the kind of competition that was supposed to characterize a newly-free nation's optimistically vaunted "free market." But as Cyril Tuschi's long-time-in-the-making, labor-of-love documentary Khodorkovsky shows, the man is a grey streak a mile long, a personage impossible to jump to facile conclusions about or make snap judgments on -- a Zelig-like chameleon who, in various significant and fascinating ways, has both passively reflected and exerted undue influence upon the nation and society of which he became perhaps the most world-famous, then internationally notorious and galvanizing, member.

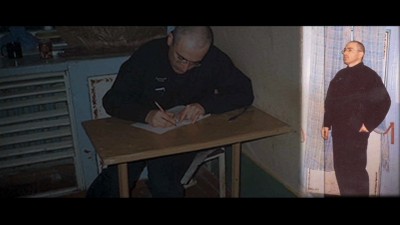

Tuschi opens on a vast white tundra containing, in the distance, one of the oil derricks that once belonged to Yukos, the fuel concern that the ambitious Khodorkovsky built and led to a world-class status to rival ExxonMobil; his camera then pans over, past an old building sporting a number of those centuries-old minarets that architecturally typify "Russia" to us foreigners, to land on a close-up of a few contemporary Russian youths, who engage with the camera and each other in a scripted conversation-snippet about Khodorkovsky. It's an evocative laying of cinematic groundwork, by far the most elegant and choreographed live shot (there are also intercut, animated dramatizations of Khodorkovsky's arrest and imprisonment, of which the bold, sharply-lined style somewhat recalls Ari Folman's Waltz with Bashir) in a film that by necessity relies heavily upon news footage, archival material, and whatever interviews Tuschi could muster (there's a whole sequence devoted to showing us doors metaphorically slamming in his face as he's given the runaround on the phone by potential interview subjects' secretaries). This variety of styles cut together forms something of a patchwork-puzzle that's very apt for the man the film's about: What Tuschi tells us about him leads us to most fairly summarize him as a benign, even benevolent opportunist-chameleon who has always had his ear to the ground and his finger up to measure the political winds; was always in the right place at just the right time; and whose very imprisonment, an event he could have easily predicted and avoided, is seen by some as a calculated move to make the transition from filthy-rich businessman to people's-martyr politician.

Less than a minute of interview time with Khodorkovsky himself was granted to Tuschi (in 2010, at his second trial, through a glass cage at the back of a courtroom), so instead, in addition to his own interview footage and commentary, he has actor Jean-Marc Barr (Europa) narrating over stills and relevant clips from Russian TV as well as Harvey Friedman (Valkyrie) reading in voice-over from a couple of letters Tuschi managed to receive from Khodorkovsky wherein the prisoner expresses some insight into and regret over his past dealings, which did include a not-quite-legal (and absolutely unethical) "closed auction" under post-Soviet president Boris Yeltsin at which he managed to land his company the ludicrously high-value rights to much of Russia's oil supply at a fraction of their real worth. (The mitigating factor is that no Russians had the capital to buy it at its true price, and Yeltsin didn't want to see core Russian industry owned by foreigners; it was basically more a matter of the state selecting who would bring the industry into the capitalist era than "auctioning" the assets to the highest bidder.) He also expresses well-articulated outrage at the injustice visited upon him and all of his colleagues in Yukos, many longtime friends and associates, who, in the wake of Khodorkovsky's arrest, felt it would behoove them to flee to Israel if they were Jewish or the UK otherwise, where, as some of them tell us in interviews Tuschi did manage to snag, they received news of their own warrants for arrest, making it unlikely that they'll be able to return to their homeland anytime soon, and watched Yukos taken away and basically given (through yet another shady dealing between government and corporate interests) to a competitor.

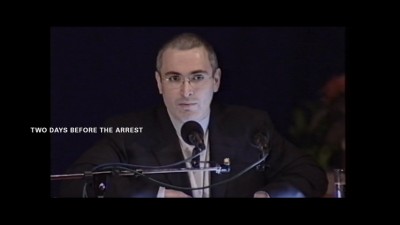

In trying to figure out why Khodorkovsky was scapegoated for open-secret "crimes" committed in collaboration with the government, the initially skeptical Tuschi finds himself, upon investigation, making a complex case for this not always on the up-and-up man, whom one interviewee describes as "the best of the worst [the post-Soviet Russian rich]." It appears that Khodorkovsky was premature in deciding that the post-communist free-for-all had run its course; around the turn of the millennium, he began an image makeover, mending his ways and making reparations in part by founding an egalitarian educational organization ("Open Russia") dedicated to furthering education and democracy for all Russians. He also publicly renounced what everyone knew was rampant ongoing corruption between industry, government, and gangsters -- a stance he took in 2003 right in the presence of notoriously egotistical President Vladimir Putin, during a very public meeting at the Kremlin between the highest officials of government and industry. Putin didn't take at all kindly to the exposure and embarrassment coming from someone he assumed was a bought-and-paid-for accomplice, and, as a former KGB agent who subsequently headed up private/corporate security for Yukos interviewed by Tuschi (one among many interestingly contradictory post-Soviet figures on display here) informs us, he knew right then that Yukos's and Khodorkovsky's time was up; the illustrious CEO was shortly thereafter arrested, put on trial, and imprisoned. In 2010, a second trial, with new president Dmitry Medvedev in office, caused a brief flare of optimism about a possible release (it is at this point that Tuschi intercuts some interviewees conjecturing on whether the ever-astute and wily Khodorkovsky willingly let himself fall prey to an arrest he knew was coming in order to become a martyr whose rebirth as a new, more left-leaning, post-privatization politics could make him a prime candidate for office himself), but Khodorkovsky was instead sentenced to six additional years in his Siberian cell. His former colleagues/friends will be stuck with the choice of exile or prison for the foreseeable future; his grown son Pavel, who currently lives in Boston and is the most sincere, thoughtful, disinterested/objective interviewee Tuschi offers us (other relations include Khodorkovsky's mother and immediate family glimpsed in home-video footage taken days before the man's arrest), takes a stoically philosophical tack on the matter but can't quite disguise the melancholy in his resignation over not seeing his father again for who knows how many more years.

My main criticism of Khodorkovsky is not exactly Tuschi's insertion of himself and his filmmaking odyssey into the proceedings (the obstacles he comes up against have much to tell us about the story he's pursuing and trying to relate), but rather the unsatisfying incompleteness of his presence, which feels like something must have been overlooked in the editing room. Whether out of modesty, neglect, or haste, he fails to follow up on hints dropped about his own personal investment in Khodorkovsky's life story and ultimate fate (he says of his subject, "He was the kind of man my parents warned me about, a neoliberal capitalist who cared nothing for art"; we infer that his parents are possibly Russian, or Soviet-era Russian immigrants to Germany, where Tuschi hails from, but he never mentions it, or anything very revealing about himself, again). The film would have been leaner and more focused, and lost nothing except mildly niggling puzzlement, had he removed himself whenever his on-camera presence wasn't necessary; it doesn't quite work as a first-person account. But that's really only meant as a frame (a somewhat tarnished one, as it turns out) for the film, and once you look past it, the main work on display proves Tuschi to be an earnest, sometimes shaky, but ultimately skilled and passionate documentarian whose obsessive fascination with a frustratingly enigmatic exemplar of the new Russia comes through fully in the film, drawing us into the obsessive quest for answers, too. Tuschi's lens takes a multilayered, revealing snapshot of Khodorkovsky that will give non-Russian viewers a refreshingly thoroughgoing, unvarnished accounting of how rocky the road has been since the Wall fell. When the film's ending takes up where the opening shot left off, panning once again very slowly, in the opposite direction, over that vast, wintry Russian landscape, it's as if to say that, in this beautiful, venerable land -- a nation populated by a wary, rightly suspicious and jaded populace, and one that has perpetually borne the brunt of history's to and fro -- meaningful change comes only at an infinitesimal pace, and any high-profile idealist who jumps the gun or tries to redeem himself out of turn can expect to pay a disproportionately steep price.

THE DVD:

The visual presentation of the film (in a widescreen anamorphic transfer preserving the film's original aspect ratio of 2.35:1) is fair to good; it appears that most of it (save for the plentiful archival footage) was shot on one form of digital video or another, so it should probably not contain quite as much aliasing and edge enhancement as is seen here (usually, DV transfers much more cleanly to DVD). The animated sequences come through most cleanly and clearly of all, and the compression artifacts are neither nonstop nor so severe as to really mar our enjoyment of the film, which one wouldn't expect to look pristine to begin with; still, the disc falls short of absolutely ideal, visually speaking.

Sound:The film's soundtrack (much of it in English, with non-optional English subtitles for Russian speech) is presented as either a more concentrated Dolby Digital 2.0 or a Dolby Digital 5.1 surround track, and both are very nicely done, with the film's various types of sound (cheap and on-the-fly videotaping, static-y archival footage, more sound-controlled prepared interviews, and a rich and sonorous sound design for the animated sequences) all retain their particular sonic properties, with no distortion or imbalance due to the transfer discernible at any point.

Extras:Just the film's slightly misleading, hyperbolic theatrical trailer and a stills gallery.

Both the story of its own making and, more principally (and more successfully), the story of an unusually conflicting figure -- something like a contemporary Russian Zelig turned self-consciously martyred, devoted-to-the-people Eva Peron -- Cyril Tuschi's Khodorkovsky is a documentary that relies on shifts in scope to convey its significance. This, for the most part, works quite well as Tuschi goes in close on the post-Soviet Russian oil-baron oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky, steps back for a medium view that also encompasses Khodorkovsky's family and colleagues (and, implicitly, the entire former-Communist-insider, more recently upper-crust-capitalist class to which they belong), and at its widest perspective reveals Khodorkovsky and his persecution at the hands of two (scapegoating?) presidents as iceberg tips that signify latter-day Russia's many roiling underlying difficulties and reversals as it continues to transform itself from the rampantly corrupt, secretive gangster-capitalist nightmare of its immediate post-Berlin Wall period into something like a functioning, mitigated-capitalist democracy with an actually representative government. Tuschi has taken on a tricky balancing act of his own, but manages it quite well, neither reducing his subject to a mere symbol or overplaying his individuality by severing him from the society, culture, and political regime(s) in which he became such a galvanizing lightning rod. Though Tuschi drops the ball somewhat on convincing us of his own connection to the events in the film and the point of his own presence in it as he tries to simultaneously document the process of its making, he has managed the fairly impressive feat of pulling together an extremely complicated story into something that coheres while still retaining all its complexities and ambiguities. Khodorkovsky is a cogently enlightening and entertaining picture that's well worth a look as a mysterious, captivating, still-unfinished story, both of a fascinatingly ambiguous real-life "character" and of the evolving society that shaped (and has in turn been shaped by) him. Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||