| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Experiment In Terror (Sony Choice Collection)

Undeniably striking at first...but far, far too long. Sony's Choice Collection vault of hard-to-find cult and library titles has released Experiment in Terror, the 1962 thriller from Columbia Pictures, directed by Blake Edwards, and starring Glenn Ford, Lee Remick, Stefanie Powers, Ned Glass, Anita Loo, Patricia Huston, Clifton James, and another actor I'll name later (but whom I'm sure you already know). An at-times hypnotic suspenser from comedy director Blake Edwards, Experiment in Terror is probably better known today for its Henry Mancini soundtrack and for its influence on director David Lynch, rather than for its own glossy-but-minor, protracted achievements. A vintage trailer is included in this sharp-looking anamorphic black and white transfer.

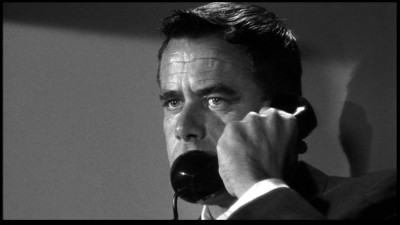

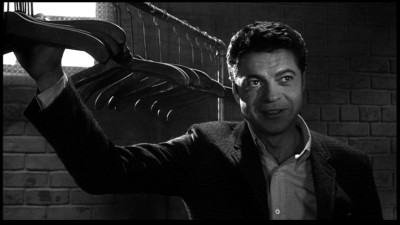

San Francisco bank teller Kelly Sherwood (the underrated, skilled Lee Remick) returns home late one night, parks her Ford in her dark garage, gets out of the car, and is grabbed from behind by a wheezing psychotic named Garland Humphrey "Red" Lynch. Lynch makes it clear: Kelly is going to steal for him $100,000 from her bank, or he's going to kill her and possibly her little sister, Toby (Stefanie Powers). He or an associate will be watching her at all times, and the minute she slips up and calls the cops, she and Toby are through. Beautiful-but-tough cookie Kelly immediately calls the F.B.I., and briefly speaks with agent John Ripley (capable Glenn Ford's last gasp as an A-lister, after the disastrous big-budget flops Cimarron, Pocketful of Miracles, and especially Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse). However, Lynch is still in her house, and knocks her to the floor, telling her she's had her last warning. Agent Ripley, believing Kelly was telling the truth, eventually tracks down her number and through veiled, careful conversation, gets a handle on Kelly's dangerous situation. He eventually meets with her, offering the Bureau's help, but Lynch is always two steps ahead of the intrepid Ripley, first knocking off potential witness Nancy Ashton (Patricia Huston), and then kidnapping Toby. Will Ripley and Kelly be able to stop Lynch before he kills again?

MAJOR SPOILER WARNING!...or sorta

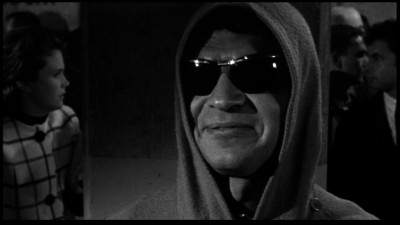

Since Experiment in Terror is fairly well known to fans of Edwards' work (it played on afternoon and late, late movie shows all the time during the 1970s and 1980s)...and since Sony puts the name of the actor playing Red Lynch right on the back DVD cover...and since anyone who's ever watched a minimum of ten hours of classic TV will recognize his distinctive voice and facial features (Edwards pretty much shows all of his face about an hour into the movie, anyway, so it's not like a big surprise), I'm going to "reveal" the actor's name in the main body of the review. If you've never seen Experiment in Terror and you want to guess who he is (at least for the first 15 minutes or so), then don't read any further. Otherwise...I did warn you....

Back during my "film school" days (bleech), I remember having a fairly heated argument with one of my "film professors" (hee hee!), who stated categorically that she didn't believe in "such a thing as a 'Blake Edwards,' whatever that is." Her comment always stuck with me, not only because of the hilariously self-righteous vehemence in which it was delivered, but, truth be told, because Edwards is a good litmus test for the limitations of the auteur theory. If the auteur theory is correct, Edwards' sensibilities, thematic concerns, and visual vocabulary, among other elements, should be discernable in most of the works he did, regardless of their genre. I used to love the auteur theory because it was the easiest one to pull out to b.s. your way through a term paper ("Professor Mimi Montage, I found meaningful shadows in these eight Murnau movies." "A+ for you, young Pavlovian protégé!"). Today, however, I find auteurism pretty much the way I find most of those theories that were drilled into our heads back then: esoteric gossamer that are the over-codified, over-intellectualized equivalents of parlor games.

Certainly, there are experts out there on Edwards' movies who believe his unique signature can be found in all his movies, and to them I say, "more power to you." When reading his advocates, I always get the feeling they're going out of their way to champion his non-comedic outings like Experiment in Terror precisely because he could be so brilliant at comedies―a classic overcompensation by-product of the auteur theory for any filmmaker largely associated with one genre. In Edwards' case, it's that old canard about comedy somehow not being worthy in and of itself; a moviemaker has to bolster those humorous abilities with...something more (a good example: most historians have long-praised Chaplin and Keaton as somehow "deeper," more significant artists than mere "laugh-getter" Lloyd). And yet clearly, Edwards' non-comedic efforts don't come close to what Edwards achieved in his justifiably more famous humorous outings. It's enough for me to acknowledge that Edwards was frankly brilliant with Peter Sellers (A Shot in the Dark is, for my money, one of the best directed comedies ever); I don't need to make a case that aesthetic misfires like Wild Rovers, Darling Lili, The Tamarind Seed, and indeed Experiment in Terror, are cohesive, inter-connected works which are better than they actually are, just to validate Edwards as a "legitimate" auteur director.

Experiment in Terror is a good case in point. As many critics have already acknowledged, Experiment in Terror's opening sequence is bravura moviemaking, a slick, sinister sequence that promises the viewer a nail-biting thriller with decidedly perverse undertones, particularly for a mainstream 1962 Hollywood mystery. Edwards, critically with the help of his foremost collaborator, composer Henry Mancini (as important, if not more so, to Edwards' reputation as Herrmann was to Hitchcock's), sets up a creepy, nightmarish world with Mancini's languid, sly, buzzy electronic-and-strings theme punctuating Edwards' and cinematographer Philip H. Lathrop's dark, shadowy frames of Frisco nightlife. After the opening credits, once we're inside Remick's garage, Edwards shoots wheezing, rasping Ross Martin in complete shadow, as a high key light harshly illuminates part of Remick's face, her terrified eyes reacting to Martin's threats as his one hand roams over her body, getting her "measurements" right. It's a remarkably modern, fetishistic scene, eroticizing themes of stylized violence and submission (we can't stop thinking about how beautiful Remick's absolutely perfect features look in that key light...as he grips her throat), which Edwards brings to an even sicker sexual pitch once Martin "teaches" Remick a lesson for calling Ford―by putting his foot on her neck as she groans into the carpet. Watching these hypnotic scenes, you can see precisely where young David Lynch first went "wrong" in his psyche, while wondering what kind of ride you're in for after this remarkable opening.

Unfortunately, Edwards can't sustain (or even adequately revisit) this heightened, otherworldly/sick suspense, and Experiment in Terror almost immediately winds down into an enjoyable but distressingly routine―and far too protracted―procedural. Edwards always had a problem with pacing and with focus (that's a "fault," not a "signature"), a weakness less noticeable in his comedies because of the audience's willingness to just bump along with him from stand-alone set piece to set piece (The Great Race), but a telling fault in his more conventional dramas and thrillers (the gargantuan Darling Lili and the meandering Wild Rovers, The Carey Treatment, and The Tamarind Seed). It may make other school-trained "film theorists" derisively snort to reference a caveman reviewer like all-over-the-map Bosley Crowther (and that's precisely why I like to do it), but he was exactly right in his 1962 review about Experiment in Terror's biggest drawback―its padded overlength―before he had the benefit of any theses on Edwards' oeuvre.

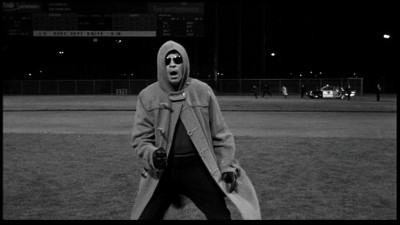

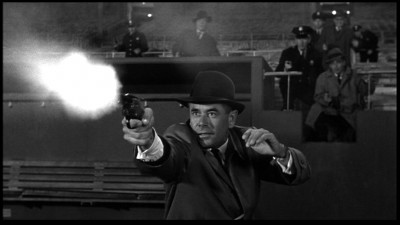

A thriller's primary goal is to thrill, obviously, but Experiment in Terror takes a long 122 minutes to clumsily resolve its suspense, with at least a half hour of it unnecessary filler and repetitious scenes that likely would have been chopped out if director Blake Edwards' producer had been anyone other than Blake Edwards (whenever they fully gave Edwards' his head...he ran into problems). With a screenplay by crimewriting duo The Gordons (their Disney favorite, That Darn Cat, was an amusing little mystery), Edwards cuts back and forth between Glenn Ford's stolid, coincidence-ridden investigation and Ross Martin's hammy phone hijinks with Remick and Powers, stuffing inbetween them unnecessarily drawn-out sequences with mannequin maker Huston (her vague character is only a prop to show Martin killing someone other than Remick), stoolie Ned Glass (a too-genial pulp stereotype right out of Peter Gunn, clashing with Experiment in Terror's modernism), and Anita Loo (exactly how many times did we need to see that kid of hers?). As far as the procedural elements go, you had tighter, more succinct investigations in any four average Dragnet episodes, while Edwards' attempts at "atmosphere" go noticeably flat (the whole ungodly long "Roaring Twenties" bar sequence with Remick being mistaken for a hooker fails not only as a red herring, but as informative subtext). By the time everyone is running around Candlestick Park at the end, you're not noticing Edwards' surprisingly clumsy shoot-out (the crowded chase in the bowels of the park is alright, but the pitcher's mound finale is, ironically, wrapped up too quickly), but rather how Martin, in his hoodie mackinaw and dark glasses, looks like a cross between the Unibomber and one of The Omega Man's "Family." You can't open up a movie so brilliantly like Experiment in Terror...and then coast into conventionality―no matter what kind of auteur genius you may be.

The DVD:

The Video:

The anamorphically-enhanced, 1.85:1 widescreen black and white transfer for Experiment in Terror looks fairly good, with a sharpish image, decent blacks and acceptable contrast, and expected grain.

The Audio:

The Dolby Digital English split mono audio tracks is at least re-recorded at a decent level. No subtitles or closed-captions available.

The Extras:

An original trailer is included.

Final Thoughts:

Trim a half-hour out of it...and you still have a fairly conventional thriller. There's no denying that director Blake Edwards' opening sequence for Experiment in Terror is brilliant, suspenseful, perverted moviemaking. However, opening sequences alone do not make successful movies, and Experiment in Terror has another protracted 110-odd minutes to go after this initial creep-out. A lot of fat on promising B-material; however, if you're in an undemanding mood, you can still mildly enjoy Experiment in Terror as a vintage thriller. On that level, I'm recommending Experiment in Terror.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published movie and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||