| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

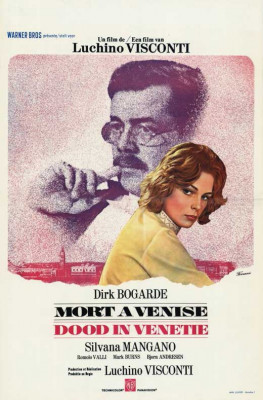

Death in Venice

In retrospect, many of the greatest films of the 1965-75 years were either dismissed or, more commonly, weren't even on most critic's radar. The majority of emblematic titles from this time remain highly thought of, but others, like Luchino Visconti's Death in Venice (Morte a Venezia, 1971), haven't aged well. Its cinematography and art direction still impress but, as a movie, its insufferable pretentiousness and unsubtle execution today play almost like a parody of a ‘70s arthouse film, like the film-within-the-film Antonioni spoof in Orson Welles's The Other Side of the Wind.

Visconti adapts German writer Thomas Mann's 1912 novella of the same name, but makes several significant alterations. Visconti decided that the story's protagonist, Gustav von Aschenbach (English actor Dirk Bogarde) was based on Gustav Mahler, so he changed his profession from esteemed writer to esteemed composer, has Bogarde made up to resemble Mahler, and drowns the film in Mahler's Third and Fifth Symphonies.

Aschenbach arrives in Venice hoping to recover his health, following a near-fatal heart episode seen in flashback. Slovenly but overdressed for the climate, fussy yet introverted, he seems wildly out of place among the happy holidaymakers staying at the Grand Hotel des Bains on the Lido. In the lobby, dining room and stretch of beach beyond, Aschenbach gradually becomes obsessed with Tadzio (Björn Andrésen), an adolescent Polish boy vacationing with his large family. They exchange glances - many, many glances - but never actually converse, let alone have anything approaching physical contact.

Unsure of what to make of this profound compulsion for the boy, the married family man Aschenbach becomes grumpy with the subservient hotel staff and leaves in a huff, only to happily U-turn it back to the hotel after his luggage is lost. As his health further deteriorates, the rest of Venice is threatened by a cholera outbreak.

Though a great admirer of other Visconti films (The Leopard, Rocco and His Brothers, etc.), Death in Venice plays like the director thought he was expressing homosexual longing with great subtlety, even ambiguity, when the opposite is true. In this sense I was, oddly, reminded of Randal Kleiser's ludicrous film of Henry De Vere Stacpoole's The Blue Lagoon (1980), sold as "a sensual story of natural love" between two adolescents but which, in fact, is much more about Kleiser's Adonis-like presentation of the boy, played in that film by Christopher Atkins.

In Death in Venice, Tadzio's come-hither glances have all the ambiguity of a male hustler. In Mann's novella, Aschenbach's attraction is much more complex, implying Aschenbach is reading more in Tadzio's (possibly perfectly) innocent smiles than he assumes. In the book, the physical, unaffected perfection of the boy rattles Aschenbach's purely analytical sensibilities. To distill it to repressed homosexual passion would seem to cheapen the very core of Mann's story. Flashbacks of Aschenbach debating the nature of beauty, with the composer taking the position that beauty is a purely intellectual conceit, are heavy-handed and obvious. Indeed, all the flashback scenes are notably clumsy.

Though officially an Italian-French, co-production, Warner Bros. apparently heavily invested in the $2 million production as well, and the English-language version with its English star seems to be the "official" cut. Indeed, Criterion has chosen not to include an Italian-language version at all, assuming one exists. Possibly for these reasons and with an eye on the international market, the film has a strange quality, with long scenes in Venice with little dialogue (with most of the exposition and philosophizing limited to the flashbacks). With Aschenbach and Tadzio staring at one another, the lack of meaningful talk draws attention to the filmmaking techniques. In these scenes Visconti favors opening shots in wide angles, then frequently zooming in on one or the other, while other vacationers are heard as background noise, making stereotypical touristy comments among themselves. The effect is rather like Mr. Hulot's Holiday or Playtime without the laughs.

One imagines that the film's coy yet straightforward treatment played much edgier and alluring to arthouse audiences then than it does now. On the other hand, its story of a 50-something year-old man - who resorts to whitening his face and wearing lipstick to change his appearance - longing for an adolescent boy, invites comparisons to the recent renewed interest in Michael Jackson's pedophilia, the timing inadvertently adding an unseemly air to Visconti's film. (For the record, Visconti was openly gay, while former matinee idol Bogarde was closeted, with a longtime partner.)

Pasqualino De Santis's cinematography otherwise exudes the subtlety Visconti's screenplay and direction lacks, presenting a more ominous, burnt-orange Venice than the picture postcard manner in which the city is usually presented. Likewise, the costumes and art direction, rightly acknowledged at the time, work in tandem to create an authentic period feel.

Video & Audio

Filmed in Panavision, Death in Venice is presented here in a new 4K restoration from the original camera negative with an uncompressed mono soundtrack. The high-def nature brings out a much cleaner and subtler color scheme than can be gleamed from Warner Home Video's earlier DVD version. English SDH are available but, as mentioned above, no alternate language versions are offered. Region "A" encoded.

Extras

Supplements include the odd, frustrating though informative 2008 documentary Luchino Visconti: Life as a Novel; Visconti's 1970 film Alla ricercar di Tadzio about his efforts to cast that role, and another short behind-the-scenes film from that same year, Visconti's Venice; an on-camera interviews with costume designer Piero Tosi, and scholar Stefano Albertini; excerpts from a program about the use of music in Visconti's films; and a trailer.

Parting Thoughts

Halfway through watching Criterion's Blu-ray I took a short break and my wife, hearing Mahler seeping through the ceiling separating us, asked if I was watching Death in Venice. After listening to my criticisms, she countered that it was one of her favorite films. "Why?" I asked. "Because that boy is beautiful! You don't get it: it's a movie for women and gay men," she insisted. Maybe so. It still doesn't work for me, with its visual sumptuous, more obvious in this Blu-ray release, only accentuating the weakness of its adaptation. Still definitely worth seeing once, and for its presentation and its supplements it's Recommended.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian currently restoring a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||