| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Lucille Ball Film Collection (Dance, Girl, Dance / The Big Street / Du Barry Was a Lady / Critic's Choice / Mame)

Dance, Girl, Dance (1940) is notable in that it was directed by Hollywood's lone woman director for many years, Dorothy Arzner, and during the 1970s the film attained a minor cult status for its supposedly feminist sensibilities, particularly in a big speech delivered at the climax by top-billed Maureen O'Hara (then just 20 years old and at the beginning of her 62 year-long screen career). Unfortunately, the film isn't very good, and Arzner's direction is notably clunky, the film shot and cut (in part by a young Robert Wise) more like something from the early talkie period of 1927-29 than a film from 1940.

Judy O'Brien is an aspiring ballerina whose poor finances have reduced her and her mentor, Madame Lydia Basilova (Maria Ouspenskaya, of The Wolf Man fame), to corralling cheap chorus girls for local nightclubs. They have a rising star in "Bubbles" (Lucille Ball), a dame with ambition to spare for both her career and bank account. When Bubbles leaves the act and becomes a Broadway headliner, she cruelly hires the desperate Judy to dance ballet immediately after her own act - knowing full well that the lecherous audience, outraged by O'Brien's delicate onslaught of "culture" will be met with hostile "boos" and demands that Bubbles (now rechristened "Tiger" Lily White) return for an encore.

The film affords Lucy with a great role to be sure - her cutthroat entertainer will come as a big surprise to those that only know her from her sitcoms - and O'Hara is lovely and sincere as hapless Judy but the entire film is so lacquered with overwrought sentiment, incredible coincidences, and hard-to-swallow misunderstandings that at times it plays rather like a 19th century melodrama.

Ball's penultimate film for RKO, The Big Street (1942), is an adaptation of Damon Runyon's Little Pinks and was personally produced by Runyon himself. Though films based on his stories had been hugely successful from the 1930s (Little Miss Marker) to the 1950s (Guys and Dolls), the appeal of Runyon's colorful (and colorfully-named) gangsters, gamblers, and show-biz types seem awfully dated today - does anyone still actually read his stuff? - and the crux of this particular film's drama hinges on a conceit too pathological to work as entertainment or drama.

Henry Fonda stars as friendly but cripplingly introverted "Little Pinks" Pinkerton, a lowly busboy at a swank nightclub where he pines away for its goddess of a showgirl, Gloria Lyons (Ball), a spoiled and abusive bitch looking to marry the first millionaire she can get her greedy little hands on. When mobster Case Ables (Barton MacLane) knocks her silly, sending her down a paralyzing fall down a flight of stairs, she becomes bedridden, unable to perform, and her rich friends and associates drop her like a hot potato.

Little Pinks, whose slavish devotion goes unabated, vows to look after her, insisting that she move into his tiny flat. Gloria however, is unmoved and utterly ungrateful, taking her rage and self-pity out on Little Pinks and all of his friends and neighbors. He's a saint but she's not worth saving. Audiences are supposed to admire Pinks's unwavering kindness but instead he comes off as extraordinarily foolish, like the prepubescent girls who regard Paris Hilton as some kind of role model.

Though it's easy to imagine 1942 audiences of middle-aged and older women sobbing their eyes out watching The Big Street, its melodramatics make Dance, Girl, Dance seem enormously restrained by comparison. The film's typically Runyonesque characters are at least well-played. It's a strange indeed noting that, immediately after giving stellar performances in Orson Welles' The Magnificent Ambersons, Agnes Moorehead and Ray Collins were saddled with a film as trifling as The Big Street, though both are excellent in supporting roles. Moorehead plays the love interest of fat, bullfrog-voiced Eugene Pallette, and their scenes together offer the picture's only real charm. Fonda goes for broke as the dedicated schlub, but this variation of his far superior characterization is Preston Sturges' The Lady Eve (1941) is hardly worth the effort.

Du Barry Was a Lady (1943) is a typically overproduced MGM musical comedy positively oozing in Technicolor and production values - and slapstick delivered with all the finesse of a sledgehammer. Produced by Arthur Freed, the film is something of an ensemble piece, an A-picture tryout for homegrown rising stars Red Skelton (who had graduated to starring roles just two years before), Gene Kelly (in only his third film), and Ball, she having just moved over to Metro from RKO. Perhaps uncertain that any of the three leads could draw in crowds on their own, the picture is buttressed with a host of names from radio and Vaudeville, including Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra and, in his film debut, Zero Mostel.

Red plays Louis Blore, a hatcheck boy at the kind of nightclub that only ever existed in the movies, the kind where the performers on a football-field-size stage greatly outnumber the paying customers. Both he and penniless dancer-songwriter Alec Howe (Gene Kelly) are in love with the club's headliner, glamorous redhead May Daly (Ball). Once again, Ball is an entertainer looking to marry into money rather than for love, the kind of typecasting that, probably more than anything else drove her into radio sitcom land and, eventually, television.

When Louis suddenly wins a fortune, she decides to marry him instead of Alec, whom she obviously prefers, but then the film's last third abruptly shifts gears as Louis is knocked out cold by a Mickey Finn and dreams that he's King Louis XV, with the rest of the cast assuming dual roles also.

MGM's singular ineptitude with film comedy is less apparent or offensive here mainly because the film is such a parade of marvelous talent and Karl Freund's lensing is so opulent that there's always something to keep one's eyes at least occupied when the over-production and lame scripting bog things down. Buddy Rich cuts loose in Dorsey's band while The Pied Pipers, Six Hits and a Miss, The Three Oxford Boys, and The Music Maids all put in appearances, though most of Cole Porter's Broadway score has been replaced save for "Friendship," heard at the end.

Besides Mostel, very good, the underrated, deadpan comedienne Virginia O'Brien is delightful as a cigarette girl pining after Skelton; she has one great number, "Salome." The Wizard of Oz's Clara Blandick has a nice little scene with Skelton and Ball, and Ava Gardner and Marilyn Maxwell have tiny unbilled bits.

Ball, frankly, is little more than scenery in this outing, though she was never photographed better, certainly an incentive to hire DP Freund later for I Love Lucy. More interesting to watch is Kelly; he hardly gets to dance but it's interesting how even here, so early in his career, he's already got his screen persona locked into place.

Critic's Choice starts out bland and predictable, then gets dramatically confused and excruciatingly unfunny and sloppily sentimental. The film is fatally miscast from the get-go, with Lucy second-billed as Angela Ballantine, a housewife who aspires to write a successful play for the Broadway stage, with top-billed Bob Hope as Parker, her pithy Addison DeWitt-like theater critic husband with a poison pen, a man none-too-happy to find his wife taking up writing.

Bob Hope as a sharp-tongued theater critic? Lucille Ball as a would-be Lillian Hellman? The film was based upon a moderately successful stage play itself, written by Ira Levin and directed by none other than Otto Preminger. Henry Fonda and Georgann Johnson had played the Hope and Ball roles onstage for 189 performances. Whatever appeal the play held, the film has been refashioned, awkwardly, for Hope's screen persona. For instance, when Parker throws out his back at his son's Little League game, he tells his psychiatrist-neighbor (Jim Backus), "Do something Doc, I feel like an anteater."

The crux of the drama is the conflict between Parker, who constantly puts down his wife's chances of making a go of it writing plays, and her determination to succeed in spite of his insistence that her maiden effort isn't any good. When the show finally hits Broadway, she doesn't want him to review it because he's already predisposed to hate it, while he insists he must review it to maintain his critic's integrity.

This might have worked in the Fonda-Johnson play version, but as presented here this conflict is a dramatic disaster. For one thing it's hard to take Parker's ethical standards seriously. In the movie we see him review just two plays, both of which he pans mercilessly - yet he walked out of the first one before it was over and arrives totally drunk halfway through the second, creating a theater-wide disturbance no less, but reviews them anyway. Some standards.

The craft of writing and the supposed merits (or lack their of) of Angela's play is the kind of stuff next to impossible to dramatize in compelling cinematic terms, and by the end of the film the movie audience has no idea whether her play was worth the effort or not. Instead, the film shifts focus away from her labors and toward an exceedingly dreary love triangle with the play's hot young director (31-year-old Rip Torn) muscling in on Parker's 51-year-old wife.

The film is superior to all of Hope's later starring vehicles, but that's saying very little. It's a polished production at least, but lugubriously paced by prolific television director Don Weis. At least the supporting cast is good, with Marilyn Maxwell sharing screentime as Hope's first wife, Jesse Royce Landis as Ball's mother, and Marie Windsor and Joan Shawlee well-cast as Ball's two sisters. John Dehner is in there as Lucy's producer, while Jerome Cowan has a nice scene or two as Hope's boss. Soupy Sales has a nice uncredited bit as a hotel front desk clerk.

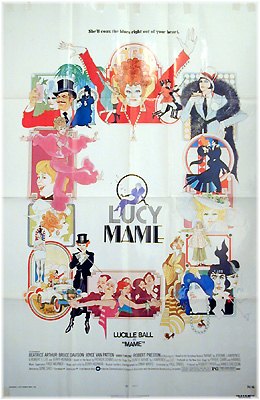

Mame (1974) had been a successful novel (Auntie Mame, by Patrick Dennis), a Broadway play and 1958 film with Rosalind Russell, and in 1966 a long-running Broadway musical starring Angela Lansbury, with music and lyrics by Jerry Herman. Indeed, the musical of Mame seemed to run forever, more than 1,500 performances in New York while a West End production with Ginger Rogers did very well also, running some 14 months.

Lucille Ball coveted the role of Auntie Mame in the movie adaptation, though her exact role behind-the-scenes is unclear. The IMDb reports that Ball put up $5 million of her own money just to be considered for the role, but that claim seems dubious. In any case she got the role, with one exception her first starring movie in more than a decade, made just before her last season on Here's Lucy, Ball's last successful sitcom.

Clearly part of the Broadway show's appeal had been due to its timing, with Auntie Mame a counter-culture revolutionary living a Jazz Age bohemian lifestyle that in some ways mirrored the emerging flower children of the late-1960s. The story spans several decades, with Auntie Mame (Ball) suddenly charged with caring for her late, very conservative brother's son, a 10-year-old named Patrick (played as a boy by Kirby Furlong). She introduces him to a world of burlesque houses, Cubist art, skydiving, progressive schools, speakeasies and the like, living by her motto, "Life is a banquet and most poor sons-of-bitches are starving to death."

With the Great Depression Auntie Mame loses all her money but forges on with the help of secretary/nanny Agnes Gooch (Jane Connell), manservant Ito (George Chiang) and especially best pal Vera Charles (Beatrice Arthur), a sardonic operetta star and Big Time lush. Mame eventually meets southern aristocrat Beauregard Jackson Pickett Burnside (Robert Preston) while her nephew grows up (and played by Bruce Davison) to become a snob.

Ball was 62 years old when she made Mame, but then again Ginger Rogers was nearly that when she did the show in London. Nonetheless, cinematographer (and/or Ball) made the fatal decision to shoot all her close-up in extreme soft-focus, as if an entire jar of Vaseline had been smeared over the Panavision lens. Though it would be unfair to assume Ball's singing was as off-key as Lucy Ricardo, her years of heavy smoking by 1974 left her with voice akin to movie tough guy Lawrence Tierney. She croaks through the show's songs with painful earnestness while her dancing, though somewhat better, was hampered not just by age but also by a 1972 skiing accident in which she broke her leg and had not fully recovered.

All this gets in the way of what otherwise isn't a bad performance. Audiences unfamiliar with her years on TV would likely be more forgiving, but her sitcom work was in fact so engrained into the American consciousness that, as good as she is as an actress in Mame, it was hard for audiences to think of Ball any other way.

Similarly, the movie isn't too terrible beyond these not insignificant flaws. Beatrice Arthur is terrific in the role she originated on Broadway, and her then-husband, Gene Saks, likewise was carried over from the Broadway production. Indeed the film's failure was as much a product of ill-timing as Ball's miscasting: it looks, strangely enough, like a late-1950s movie musical of a 1966 show, and certainly nothing like anything produced in Hollywood in the mid-1970s. By then the movie musical was all but dead, but in its favor Mame overall is moderately entertaining on its own terms. It's not the misguided disaster of Lost Horizon (1973), the train wreck of Star! (1968), nor the total bore of Man of La Mancha (1972).

Video & Audio

Dance, Girl, Dance, The Big Street, and Du Barry Was a Lady are presented in their original full-frame format in strong transfers. Warner's RKO film elements are in notoriously bad shape in many instances, but the two RKO titles here both look well above average. Du Barry Was a Lady, in three-strip Technicolor, is a beauty. There's a stray minute or so when the three elements aren't in perfect alignment, resulting in a blurred image, both otherwise it looks fantastic.

Critics Choice and Mame are 16:9 enhanced widescreen, with both presented in good approximations of their original 2.35:1 Panavision releases. All five titles are mono, including Mame. That film might conceivably have had a multi-track stereo release (it premiered at Radio City Music Hall) but, then again, perhaps not. Optional French and English subtitles are included.

Extra Features

As usual, Warner Home Video has supplemented each disc with short subjects, usually a one or two-reel live action short (Pete Smith "specialties," etc.) and a cartoon.

Parting Thoughts

Die-hard fans of the actress will want to pick up the Lucille Ball Film Collection, while fans of classical Hollywood cinema will for various reasons find all five titles worth seeing once though probably never again. Recommended.

Film historian Stuart Galbraith IV's most recent essays appear in Criterion's new three-disc Seven Samurai DVD and BCI Eclipse's The Quiet Duel. His audio commentary for Invasion of Astro Monster is now available.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||