| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

TCM Greatest Classic Films: Murder Mysteries (The Maltese Falcon/The Big Sleep/The Postman Always Rings Twice/Dial M for Murder)

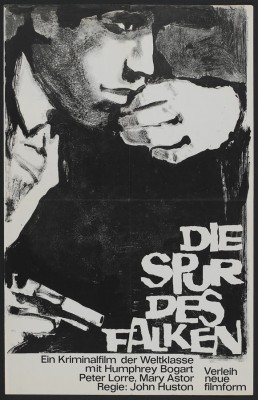

The Maltese Falcon, adapted from Dashiell Hammett's 1930 novel (though first serialized in the pulp Black Mask in 1929), was a landmark film in many respects: it marked screenwriter John Huston's directorial debut, and it was instrumental in establishing Humphrey Bogart as a leading man. Along with The Big Sleep it remains the definitive private eye movie and simultaneous to that a seminal work in the evolution of film noir. It's also extremely entertaining, mesmerizing from its first frame to its last.

Indeed, people unaccountably averse to anything made before 1995 and especially anything in black and white are invariably impressed by The Maltese Falcon - if, that is, you can get them to sit down and watch it. Among the tiny handful of classic movies Middle America will still unhesitantly sit through - The Wizard of Oz, It's a Wonderful Life, The Ten Commandments - The Maltese Falcon seems to require a bit more of a push to get them started, but once underway even jaded 2009 audiences will be hard-pressed to look away.

The complex but entirely understandable plot has private eye Sam Spade (Bogart) mixed up with a gang of shady characters all after an elusive but priceless 16th century statuette: a solid gold, jewel-encrusted falcon, its true value hidden under a coating of black enamel.

Spade becomes involved when his disreputable partner, Miles Archer (Jerome Cowan), is murdered while tailing a man at the behest of a client, Brigid O'Shaughnessy (Mary Astor), a ruthlessly manipulative chronic liar with whom Spade nevertheless becomes attached. It gradually becomes clear O'Shaughnessy is using Spade to get her safely to the black bird before her equally unsavory competitors: flamboyantly dapper Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre), articulate and physically enormous Kasper Gutman (Sydney Greenstreet), and Gutman's gunsel, sadistic but insecure Wilmer Cook (Elisha Cook, Jr.) - all coded homosexuals, though Cairo most explicitly so in this adaptation.

The novel had been filmed twice before. The 1931 film, also called The Maltese Falcon, is surprisingly good. It featured Ricardo Cortez as Spade and Bebe Daniels as O'Shaughnessy, with Thelma Todd as Archer's sleazy wife and Dwight Frye as Wilmer standing out in particular. The forever-grinning Cortez is a bit hard to take, but the pre-Code film is more explicit than Huston's, and in some respects as explicit as Hammett's raw original novel, with overt sexual references Huston could only subtly suggest. The second film version, Satan Met a Lady (1936), changed the name of all the characters (and even the sex in one instance) but was instantly recognizable, with Warren William as Spade and Bette Davis O'Shaughnessy. That film is almost unbearably bad, worse even than its poor reputation.

Of his version, director-screenwriter John Huston liked to say he simply filmed the book, but that's modest oversimplification. The pretty good 1931 film is faithful, too, but isn't half the film Huston's is. What he did was a model of how novels and movie remakes should be (but rarely are) done. He carefully distilled all the best material from the novel and through his direction - shot compositions, editing, the actors' performances - enhanced the material at each and every step, adding depth without substantively altering anything.

Everything about the film is spot-on. Every performance is exactly right, even minor but memorable ones from character actors like Barton MacLane (as the "bad cop" always giving Spade a hard time), Jerome Cowan (as Spade's slippery partner), and John Hamilton (as the short-tempered District Attorney). Of course, the film made a movie star out of 61-year-old Greenstreet, in his film debut, and rescued the career of Peter Lorre (an unabashed delight here), whose career was in freefall after his contract (and "Mr. Moto" film series) at Fox had expired.

At the center of all this, of course, are Bogart and Mary Astor, she the vastly underrated late-silent and early-talkie star who survived a major scandal and hung on as a character actress until she retired in the mid-1960s. Ironically, Astor was one of the very few completely natural, unaffected performers of the Dawn of Sound, yet is best remembered for her deliberately over-the-top role in this, playing - quite believably - a melodramatic, obvious liar. It's easy to underrate her contribution; many do.

If he had made no other films, Humphrey Bogart would be a major star for his work in this film alone. It's one of those pictures where practically every line and gesture is remembered and frequently quoted or referenced, especially Spade's classic first meeting with Gutman.

Not every great film holds up to multiple viewings, but whether it's a laserdisc, a DVD, a Blu-ray disc - I'm ready to watch The Maltese Falcon every few years, which means I must have seen it at least 15 times thus far. If you haven't seen it, run out and get this - you won't be sorry. (***** out of *****)

Call it sacrilegious, but despite its anachronistic setting I much prefer the 1978 remake of The Big Sleep to the Howard Hawks original. That version is a good movie to be sure, and Bogart and Bacall's chemistry is palpable, but the remake with Robert Mitchum is more faithful to Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe mystery, has a better cast overall with richer supporting characterizations, and most importantly isn't the confusing mess the '40s version is.

Both versions weave a labyrinthine tale with P.I. Marlowe hired by dying millionaire General Sternwood (played in the Hawks version by Charles Waldron) to "take care" of the blackmailer who's got the goods on Sternwood's wild, nymphomaniac daughter Carmen (Martha Vickers). However, Marlowe also suspects Sternwood's primary, if unstated motive is to learn the whereabouts of "Rusty" Regan, an adventurer who a) had been in Sternwood's employ and had become something like a son, and who b) had married Sternwood's older daughter, Vivian (Bacall), before disappearing into thin air. Before the night is over Marlowe stumbles onto a fresh murder scene where he finds the dead body of a rare book dealer (and pornography merchant, if you read between the lines) sprawled out in from of a zonked-out Carmen, high on drugs.

The Hawks version was shot in the fall of 1944 but held back for release until late summer 1946, partly so that Warner Bros. could release its glut of war-related flag-wavers first, before the real war ended in 1945, and partly to rework the film to play up the real-life romance between Bogart and Bacall. At age 20 she had made a slam-bang film debut in To Have and Have Not (1944) but who just as quickly faltered in her next release, Confidential Agent.

As the reworking of The Big Sleep makes clear, the idea was to recapture some of those To Have and Have Not sparks. In the novel and the 1978 remake (in which Bacall's part was played by Sarah Miles; Candy Clark played Carmen), Vivian is more on the sidelines, and while the carefully integrated, essentially imperceptible retakes enhance Bacall's part and offer numerous classic exchanges between the two stars, it comes at the expense of characterization and story, especially the latter.

The retakes so emphasize the racy romance between Bogart and Bacall's characters that Vivian's main function in the story, as protector of her unbalanced younger sibling, is almost completely jettisoned. (Note Vivian's utter disinterest toward Carmen in the final scenes!) The Bacall-heavy footage including, awkwardly, a song interlude, makes the already complicated plot literally incomprehensible at times, most famously in an early murder left unexplained.

The unjustly maligned remake is not just easier to follow; it's faithful to Chandler's explicitness in ways the Production Code would never have permitted in 1944; even the clever double-entendres of screenwriters William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, and Jules Furthman can't keep up. It's also got a superior, star-studded cast that really fleshes out the many supporting characters; surprising that Warner Bros. and/or Hawks opted to cram the film with third-tier players like Louis Jean Heydt and John Ridgely instead of character stars like Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre. While it's fun to see (a brunette) Dorothy Malone in an early role and B-Western cowboy Bob Steele surprisingly menacing as assassin Lash Canino - Richard Boone's even better in the remake - conversely Martha Vickers is inadequate as Carmen, and actors like Ridgely (as gangster Eddie Mars) and Charles Waldron make little impression.

On the other hand, it's also two hours spent with Bogart and Bacall, both on fire, and the film is wonderfully moody with especially good art direction and music by (of course) Max Steiner. Despite my complaints it's still a classic of its kind; but at the risk of sounding like Kanye West (at the MTV Music Video Awards) the remake is quite good on its own terms, and deserves to be better known. (****)

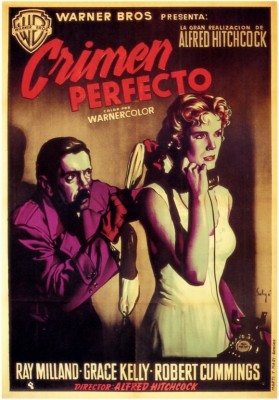

No mystery here. Alfred Hitchcock's Dial M for Murder is more of an antecedent to the later Columbo series than a conventional mystery - not a "whodunit" but rather a "howcatchum." Adapted from Frederick Knott's popular Broadway play, nearly the entire film is confined to a single room and isn't especially well regarded - few Hitchcock fans and scholars would place it in his Top Ten - and yet, somehow, it's hugely effective nonetheless. The reasons have more to do with the clever source material and the performances rather than Hitch's direction or the fact that this was shot in 3-D.

Set in London, Ray Milland stars as Tony Wendice, a recently retired tennis pro (with Milland fleshy and nearly 50, this comes off as rather preposterous) married to wealthy Margot (Grace Kelly). She's been having an affair with American Mark Halliday (Bob Cummings), yet neither realizes that Tony found out about it some time ago and has been carefully plotting Margot's murder.

Tony blackmails an old college acquaintance, C.J. Swain (Anthony Dawson), to murder Margot while Tony's off with Mark at a party at a nearby hotel, thus establishing Tony's airtight alibi. However, Swain's attempt to kill Margot goes wrong when - while he's in the midst of strangling her - she instead manages to kill him with a pair of scissors. Shaken but undeterred, Tony slyly steers Inspector Hubbard's (John Williams) investigation toward the inexorable conclusion that Margot murdered blackmailer Swain from revealing her relationship with Mark.

The movie is basically a filmed play with little in the way of cinematic flourishes or even the carefully modulated set pieces Hitchcock was famous for. Normally he virtually cut the film together in his head during pre-production, yet Dial M for Murder has a looser feel than most of Hitchcock's '50s films; some of the cuts are even a little awkward. He wasn't terribly enthusiastic about shooting it in 3-D, either, and while the film has an unusual number of panning shots and static ones with a lot of set decoration in the foreground at the bottom of the frame, except for Margot's famously desperate grab for the shears, it's almost defiantly restrained.

Where Dial M for Murder works is in the source material: Knott adapted his own ingenious, subtle play, which carefully establishes Tony as a highly intelligent man who's considered every conceivable angle, whose unflappable, suave confidence serves him well in the first act as he sets up Swain, himself pretty oily and devious, for blackmail and murder. Later, when things go wrong, Tony's efforts to rid himself of Margot by setting her up for a capital offense are equally intelligent and believable. This is man who thinks fast on his feet, and Ray Milland gives a flawless performance.

This was Grace Kelly's first real leading role after major supporting parts in High Noon (1952) and Mogambo (1953), both of which had women billed above her. She affects a strange quasi-British/Mid-Atlantic accent that sounds a little phony, but overall she's adequate and her beauty overrides her occasional stiffness. Bob Cummings, also a bit long in the tooth for his role, makes an appealing contrast to Milland.

The character everyone remembers, however, is John Williams's crafty Inspector Hubbard, who like Columbo plays his cards close to his chest, and is highly observant during outwardly innocuous conversation. Hitchcock was wise to let him (along with Dawson) reprise his stage performance*, and it established Williams as a character star for the remainder of his career. (Perhaps like me you remember Williams as a classical music pitchman.)

For his part, Hitchcock mostly points the camera in the right direction, which sounds like a criticism but in this case is really a compliment; if this is essentially a filmed play, then Hitchcock always cuts to what the audience in the theater wants to be observing. The film holds up extremely well today, the only really damaging components are some truly terrible process shots, second-unit rear-screen stuff badly integrated with the first unit footage, and the wall-to-wall score by Dimitri Tiomkin, of which there is way too much. (****)

An essential film noir despite some censorship and casting problems**, The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946) was an extremely atypical effort by MGM, a studio better known for its wholesome, innocuous musicals than its crime films.

Based on James M. Cain's 1934 novel, the film stars John Garfield (on loan from Warner Bros.; it's hard to imagine Garfield sharing Andy Hardy's universe) as Frank Chambers, a drifter who accepts a job offer from effusive if alcoholic Nick (Cecil Kellaway) to work at his roadside diner. Frank is immediately attracted to Nick's much younger, glamorously beautiful wife, Cora (Lana Turner), who initially turns up her nose at the wanderer.

Pretty soon though the two become lovers, while Nick remains oblivious to his wife's infidelity. The secret lovers decide to run off, but ambitious Cora loses her nerve; she has big plans for herself and the diner and doesn't want to have to start all over again, her love for Frank notwithstanding.

Gradually, the two consider and begin seriously plotting to do away with hapless Nick.

MGM had little experience with noir, and it shows, though the film is quite good, and gets better in its less predictable second-half, though it's success is still undercut by Production Code restrictions that precluded the sadomasochistic elements of their relationship in the novel. Probably the film's strongest asset is that Turner's Cora is no conventional femme fatale, nor is Garfield's Frank a sap lured into her web. Instead, the characters are methodically drawn into committing murder because for them it becomes a last resort, and overwhelming guilt follows them through the rest of the picture.

Director Tay Garnett was workmanlike but brings little personal style to the film. Indeed, there are quite a few artificial cuts achieved with optically printed close-shots, implying Garnett didn't shoot enough coverage and too many standard medium ones.

The acting is variable. Garfield is outstanding, Turner is okay but isn't performing at her co-star's level, and Kellaway is simply miscast. The South African-born, Australian-raised character player specialized in loveable uncle-type parts, but Nick (who was Greek in the novel) calls for a salt of the earth, Zorba-type, perhaps more pathetic and less appealing, less predictable than Kellaway, who's almost cute. It's hard to watch The Postman Always Rings Twice and not think of other character stars better suited to the part. (Claude Rains immediately comes to mind, to name one; he's not exactly right, either, but a better choice than Kellaway.)

However, Leon Ames and Hume Cronyn are great as the determined District Attorney and sleazy lawyer who figure prominently in the story's second half. Audrey Totter has a small part near the end but likewise makes a strong impression, while Alan Reed, years before he was the voice of Fred Flintstone, makes an interesting menace as Cronyn's associate. (****)

Video & Audio

The three older films look great in their original black and white, full frame presentations. Dial M for Murder is presented full-frame, but the evidence suggests this was meant to be seen at an aspect ratio somewhere between 1.66:1 and 1.85:1. Cropped to 1.78:1, most of the film looks great though a couple of shots are overly cramped. The mono audio is acceptable, though again Dial M quite probably had stereo tracks created for its 3-D release.

All four films include English and French subtitles; The Maltese Falcon, Dial M for Murder, and Postman also have Spanish subs, while the latter two also have French audio. The four pictures are on two double-sided DVDs.

Extra Features

Though all the supplements have been available before, they're plentiful and informative. Trailers accompany all four films. The Maltese Falcon also includes an audio commentary by Eric Lax, and a "Warner Night at the Movies" with several contemporaneous short subjects. The Big Sleep does not include the pre-release 1945 cut of the film, previously available, but does include UCLA archivist Robert Gitt's comparisons featurette. Dial M for Murder includes featurettes on the film and 3-D generally, while Postman features an introduction by scholar Richard Jewell and a fascinating trailer for the 1981 remake.

Parting Thoughts

The math is simple on this release. If you already have the films in this set, you won't need to buy this. If you don't, it's a DVD Talk Collector Series Title.

* On Broadway Maurice Evans played Tony, Richard Derr was Halliday, and Gusti Huber played Margot.

** Sergei Hasenecz writes, "'Some' censorship problems is putting it mildly. To get the movie made at all, the screenwriters had to go through more contortions than a convention of Chinese acrobats."

Stuart Galbraith IV's latest audio commentary, part of AnimEigo's forthcoming Tora-san DVD boxed set, is available for pre-order, while his latest book, Japanese Cinema, is in bookstores now.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||