| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Sands of the Kalahari

"Are we going to die?"

"I don't know."

Absolutely terrific chest-beating adventure flick: strange, thrilling, and beautifully put together. Olive Films, which has the rights to market some fun Paramount library titles, has released 1965's Sands of the Kalahari, the spectacular desert survival epic from the makers of Zulu, featuring a stellar cast: Stuart Whitman, Stanley Baker, Susannah York, Harry Andrews, Theodore Bikel, and Nigel Davenport. Not nearly as successful (upon its release) or as well-known today as Baker's and director Cy Endfield's classic, Zulu, Sands of the Kalahari deserves wider recognition...a proposition helped along, hopefully, by this excellent transfer.

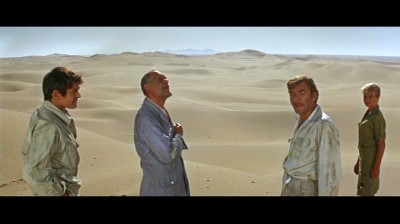

South Africa, 1965. When a commercial flight to Johannesburg is delayed, Dr. Bondrachai (Theodore Bikel), a physician working for the U.N., and Grimmelman (Harry Andrews), a German scientist, seek out other passengers to pool their money to hire a charter plane, piloted by Sturdevan (Nigel Davenport). Former Congo engineer Mike Bain (Stanley Baker), fired from his last post for drinking, is willing to go in, as is rich jetsetter Grace Munkton (Susannah York). At departure, a last-minute arrival, businessman and big game hunter Brian O'Brien (Stuart Whitman), having heard about the private charter, asks to come along. Although the co-pilot warns Sturdevan that the prop plane, already heavy with extra fuel, is dangerously overloaded now with the addition of Whitman, the brash, coarse Sturdevan waves him off―a fatal error for the co-pilot when the plane is eventually downed by a massive swarm of locusts. Stranded in the middle of the harsh, unforgiving desert, the survivors make their way to an oasis of water and rock caves, but they soon realize no one is searching for them. They have to make their way out of the desert, or they'll eventually die there: from starvation, or from one of their fellow survivors, bent on dominating the group...or from the local band of vicious baboons who watch and wait for their opportunity to strike.

MAJOR MOVIE-RUINING PLOT SPOILERS AHEAD!

Just a short but important note: there's no way to properly discuss Sands of the Kalahari without revealing the spectacular ending, so if you haven't seen it, I urge you to stop reading, and purchase the film if the above description interests you. Otherwise...you were warned.

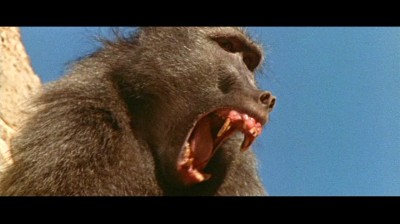

I haven't seen Sands of the Kalahari for years, but I've never forgotten it, particularly the final amazing sequence where Stuart Whitman squares off against the lead baboon in a fight to the death. Similar in structure to the more familiar The Flight of the Phoenix from 1966, where after a plane crash, the harsh desert conditions bring out the worst in people's characters, Sands of the Kalahari feels far more honest in its downbeat portrayals; some of the people make it out of Kalahari's desert...but it's not triumphant as in Phoenix. Whereas The Flight of the Phoenix plays more like an opportunity for its actors to turn in flashy, "actorish" portrayals inbetween the carefully engineered action scenes, Sands of the Kalahari offers up some disturbing, even weird dynamics that are rooted in pessimistic irony and a withering view of humanity, creating a disturbing, more depressing experience than the more conventionally entertaining The Flight of the Phoenix―with the added bonus of some spectacular action sequences, to boot.

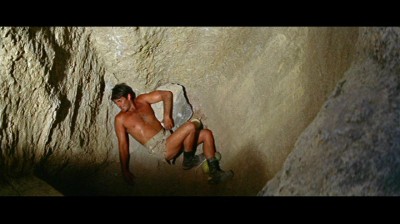

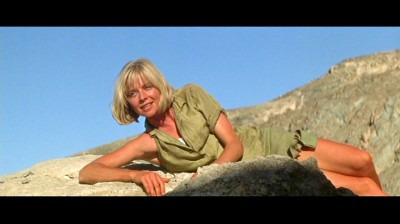

Director/writer Endfield could easily have fallen back on just presenting the exciting story as is, without further embellishment, and come up with an exciting if routine adventure movie. However, he's quite smart with Sands of the Kalahari, dropping in little moments of foreshadowing throughout the film, giving it at times a sly, ominous undercurrent. Ironic allusions to upcoming events punctuate almost every scene. Endfield never passes up a chance to show York's taut, alluring body (as we would expect in a Joseph E. Levine production), but he makes a point of showing her enjoying her shower the night before her departure, the water running off her back as she luxuriates in it―a nice contrast to what she'll soon experience in the desert. When Andrews and Bikel come to her hotel room, it's a funny little joke, appreciated later in the viewing experience, when we see Andrews' little friend: a tiny monkey on his shoulder. When drunken Baker offers York a drink on the bus, she laughs and refuses, a nice switch when she helps him weather involuntarily going on the wagon (and in one of the movie's best scenes, offering him succor by warming him as he suffers chills from an infection―gorgeous York's eyes positively glow here as she gazes right into the camera). Once in the desert, Andrews makes a point of expounding on the virtues of the bushmen of Africa and how they were mistreated by the West, before Davenport arrogantly cuts him off...an attitude that is later turned upside down when Davenport makes it out of the desert using those same bushmen's survival techniques. When first encountering their oasis, everyone is overjoyed to find shelter and water and food, but gloomy Whitman sees his own fate when he comes across a pile of bones in the deep, dry well he'll soon occupy. And when Whitman kills Andrews at the plane wreckage, it's in the same spot where Andrews saved Whitman from burning up in the plane.

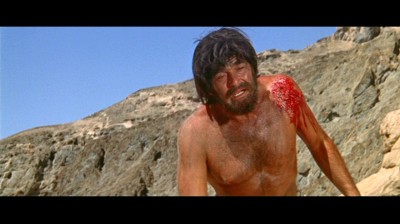

Endfield consistently sets up our expectations for a conventional adventure story with stock characters, only to pull the rug out from under us time and again. If you weren't aware of the star pecking order, you might assume that Davenport was being set up as the hero, with his commanding position of authority (the pilot of the plane), and his arrogant, dismissive tone of confidence. However, Endfield quickly turns him into a vulgar near-rapist who tries to seal the deal with York by claiming her as his right, which he fails completely at, before he does his remarkable walk-out of the desert. We promptly forget about what a creep he is while we watch his progress, hoping he'll make it...before Endfield has him crying like a baby when he's arrested for diamond smuggling after his remarkable feat. You might then believe that top-billed Whitman will be the "great white hunter" who saves the group, with drunken Baker providing tragi-comic relief, but they switch roles, as well, with Whitman's character able to perform what Davenport thinks he's capable of becoming―a caveman killer who takes a woman when he wants to...with her liking it―while drunken, nervous Baker, lame during most of the film from his injuries, gradually outsmarts the feral, savage Whitman. We admire scientist Andrews' calm, measured intelligence...until we learn he was a Nazi in the war (we wonder to what end those analytical skills were used for the war effort), and we nod in agreement with Bikel's musing about modern man "losing out" to civilization, until we see the black humor of his rescue by the intrepid bushman―the very kind of people his U.N. organization piously, stupidly think need our help.

Whitman and Baker roles are the more showy (and easier to break down), but York's character is quite complex and not immediately decipherable. Endfield never really spells out her background (we assume she's rich and bored, due to her many pieces of luggage and her generally listless attitude at the beginning), and he and York leave much of her motivation "up for grabs," if you will. When she warms the shivering, sick Baker with her body, is that a look of determination, or is she feeling needed for the first time? When she begins her flirtation with Whitman, after rejecting the crass Davenport's violent advances (another irony, because gentlemanly Whitman turns out to be the true psychotic), is she doing so out of response to Andrews' warning about the men fighting over her? When she rats out the ambushing Baker to Whitman, the film comes close to having us judge her (we think, "What a dope,"), but again, Endfield sets us up with further traitorous behavior (is she going to give that ladder to Whitman to escape his hole?) before he has her close the door on Whitman for good. So many times with these kinds of large-scale action/adventure films, the upcoming sequences are as predictable as the cardboard cut-outs standing in for real characters. That's decidedly not the case with the unpredictable Sands of the Kalahari.

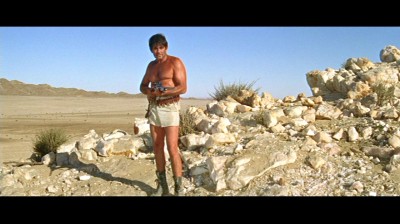

And nothing puts that approach over more forcefully than the final devolution of the Whitman character. With Whitman aware that both Baker and York know that he's a murderer, he hides out in the hills, refusing to come out to join them in the rescue helicopter (apparently sent by the same diamond mine company that arrested Davenport; we don't know what really happened to Bikel). But the viewer can also take his refusal to join them as the end result of his increasing megalomania and murderous nature, too. Bent on killing all the vicious baboons he can find, for no other reason than to satisfy his blood-lust (he even kills a mother nursing its baby), Whitman seems to see (and hate) in the baboons his own savage nature, and the self-hatred turns increasingly bloody. In a remarkable final sequence, Endfield rapidly shows Whitman reverting to basically a caveman (long hair and a beard), before the intelligent baboons, who have been biding their time, waiting for Whitman to run out of ammo, move in for the kill. Taking on the lead baboon, Whitman fights him to the death (in a well-edited, thrilling sequence), before he collapses from exhaustion. In a cold, pitiless, silent final image, the camera, placed high up in the hills, captures the little black blob that is the fallen Whitman, as the remaining baboons move in from all sides, covering him. Are they devouring him, we probably think, exacting their final revenge? Or are they going to carry him aloft as their new leader, as their instincts suggest (with a downer ending like that, no wonder the film failed to perform at the box office)? It's one of the most haunting final images I've ever seen in a film such as this, helping to elevate Sands of the Kalahari as one of the most unexpected, intriguing examples of the adventure genre.

The DVD:

The Video:

The anamorphically-enhanced, 2:35:1 widescreen transfer for Sands of the Kalahari looks terrific, with a crystal-clear, bright image, solid color, and little grain. Some minor print anomalies crop up here and there, but they're negligible. Great presentation.

The Audio:

The Dolby Digital English mono audio track is serviceable, with a decent re-recording level and low hiss. Subtitles and close-captions are not available.

The Extras:

No extras for Sands of the Kalahari.

Final Thoughts:

Smashing epic adventure, with complex characterizations and weird dynamics. Sands of the Kalahari, deserving of the same rep its filmmaker and star achieved for Zulu, is a neglected minor masterpiece of perverted heroics and ironic, cynical adventure, played out on a grand scale. The entire cast is flawless, and the direction is smart...and merciless. I'm giving Sands of the Kalahari our highest rating here at DVDTalk, on content alone: the DVD Talk Collector Series.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published film and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||