| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

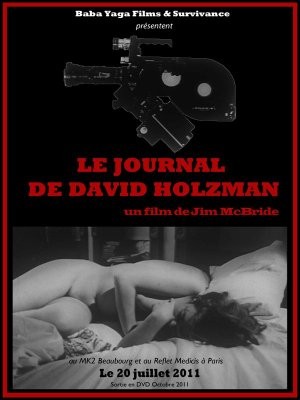

David Holzman's Diary: Special Edition

"Some people's lives are good movies, some people's lives are bad movies."

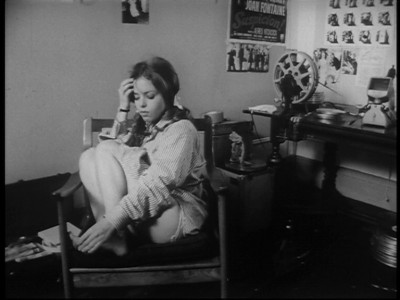

David Holzman (L.M. Kit Carson) believes in the power of cinema. His New York apartment has Spellbound and Touch of Evil posters prominently displayed and is littered with his filmmaking paraphernalia; just like his French New Wave auteur heroes Truffaut and Godard, David has an Éclair 16 mm camera, a Lavelier microphone, and a Nagra tape recorder. He even quotes, when letting us in on his project, Godard's famous dictum, "The cinema is the truth 24 times per second." David has just lost his job, has luckily received a deferral of his military service in Vietnam (the year is 1967), and is plagued with a sense of some elusive meaning, some secret significance in the world around him that just keeps escaping him and which he senses can only be pinned down on celluloid. He is therefore, he informs us, determined to spend his unemployed, un-conscripted time making a "diary" on film; he will shoot the day-to-day experience of his life in the hope that he can in this way get a grip on a reality that seems more and more unsatisfyingly opaque and just beyond his reach. The execution of this project is what we are ostensibly watching when we watch David Holzman's Diary. The film does display all the aesthetic properties of a Neorealism-inspired New Wave effort; it is shot entirely on real locations, and its wobbly handheld camerawork alternates with long, static takes, all in gloriously grainy 16 mm (blown up to 35 mm) black and white, with some nicely insouciant editing and inspired cut-ins. But it could perhaps be more aptly characterized as a precursor to a different genre, subversive in its own way: it is the (or, at least, a) prototypical mockumentary.

Right off the bat, the world around David proves recalcitrant to his mission. His girlfriend, Penny (Eileen Dietz), is not exactly turned on by having an omnipresent camera trained on her, and things go from bad to worse when she wakes up to discover she is being filmed by David while she sleeps. One of David's friends seems to have agreed to appear in the diary only on the condition that he be allowed to denounce the project, going on at some length about how bringing a camera into a situation has quite the opposite effect of narrowing it down to its "reality" or "truth," as the camera's presence will always have some altering effect on what (and who) is being filmed. This skeptical friend proves his own point, of course (he would not be declaiming if the camera was not there), but his assertions are more fully supported and developed as the diary project progressively distances and isolates David from reality and human connection, rather than rendering them more concrete and comprehensible. Increasingly dissatisfied with the camera's failure to clarify the world for him, David begins to go further, imposing odd lenses and angles as he shoots, suggesting that if recording reality with a movie camera has failed to bring it closer to him, he now feels compelled to push harder and go further, attempting to use the camera not to understand but to mold the world.

David's quest begins to seem not just inconsequential, but a corrosive agitation of his initial difficulty with non-filmed life. His once casual voyeurism (practiced through the camera viewfinder, of course) starts to become too intense, and his grandiose idealism results in not much more than a sped-up montage of his entire evening's TV-watching so we can really see what he actually saw. But, though it is "the reality" of what happened the night he watched TV for hours, he has had to manipulate the images to stave off the boredom of real time. And anyway, if he had not alienated his girlfriend with his misguided attempts to grasp "real life," would his real life not consist of a bit more than an evening alone spent filming his TV screen? How much time has David Holzman spent imbibing the shaped and plotted stories told in the movies and on television, and to what extent is what seems to him to be the unsolvable mystery of actual, real life just its normal, obstinate, everything-at-once shapelessness--its refusal to organize itself into a pattern that makes narrative sense?

Footage from Vietnam is one thing that seems to be missing from David's montage (he prefers Star Trek and the late-night movie), but Vietnam and David's lucky non-participation in that really much too "real" bit of reality is one of the first things mentioned in David Holzman's Diary, and it is a constant presence in the film, in large part via the skillfully designed soundtrack, where bits of radio news, broadcast U.N. votes on the matter, etc. make up part of that fuzzy real-world environment that seems so unreal to David. Ultimately, however, David's inability to interact without the presence of his apparatus does get him beaten up by a cop and nearly arrested, just like he might have been if he had been out protesting; but what he is protesting--the difficulty of making sense of life--is both nebulous and banal, and his act of protest is solipsistic and ineffectual.

In one of several self-interview sequences in the film, wherein he sits in front of the camera and speaks to us, offering his updates on and feelings about the project's status, he muses upon the analogous relationship between his lonely control of the world he captures on his camera and the masturbation he relies on for sexual release now that Penny is out of his life (he has an intimate relationship with his camera/companion, referring to it as "her"). Neither habit--filming or onanism--requires any dependency upon or vulnerability to human contact that might put him at the mercy of other people and their unpredictability. This way of being offers the tempting, consoling belief that maybe one really can be an island. But director Jim McBride, like his contemporary Brian DePalma (whose 1970 feature, Hi, Mom!, is thematically quite similar to David Holzman's Diary), is quite soberly aware that the camera--the cinema--may have the irresistible ability to make us feel empowered against the chaos and injustice of reality, but that feeling is slippery, illusory, and misleading. The final gesture that David Holzman records in his diary is both ironical and biting; as in Blow Out, another Brian DePalma meditation on the failure of technology to counteract messy, uncontrollable reality, the bleak implication of the film's ending is that David's technology-infatuated impulses are very resilient, and his naive belief in capturing and understanding the world by recording it--whether with cinema's 24 frames a second or through some other technological means--could potentially go on and on, long after he has been given every reason to believe that he has taken much too literally Godard's only superficially straightforward witticism about truth and cinema.

THE BLU-RAY:

Beyond bringing us the highest-def home-viewing iterations of sparklingly high-def movies, blu-ray is proving to be an excellent format with which to preserve the cinematic look/feel of older black and white and Technicolor works, even those like David Holzman's Diary that have a livelier look, often with visible grain and texture as part of their more rough-hewn 16 mm aesthetic. The 1.33:1 original-aspect-ratio transfer gives us the film in exquisite detail, with every bit of shadow and light vividly present. It is an intentionally "rough-looking" film, but we can rest assured that we are seeing it with every visual nuance intact, in a version as close as possible to how it was designed to look.

Sound:The Dolby Digital 2.0 mono soundtrack preserves all the sonic properties of the original material. This is not in any way speaker-filling cineplex stuff; but the homemade, on-the-street aural idiosyncracies are an important part of the film; there is something really gratifying about seeing that Nagra tape recorder going and realizing that you are hearing what that technology sounds like at the same time.

Extras:

McBride gives us an incredible cinematic release at the end of My Girlfriend's Wedding, after the somber nature of the Q&As and the emotionally fraught scenario of playing best man for his girlfriend's groom. He and the young woman take a hippie's-dream car trip to San Francisco, and for several minutes, we just see a fluttering succession of images from their journey. The images are beautiful, the editing remarkable; after so much stasis, however captivating, this move away from the cold, established east and toward the sunny, liberated left coast captures that go-west mythology perfectly; the editing makes it feel like racing toward freedom, however temporarily or illusorily, and it is exhilarating.

San Francisco is just a reprieve at the end of My Girlfriend's Wedding, though, and the couple return to New York. However, Pictures from Life's Other Side finds them, two years later, leaving New York for good to roam their way by car back toward Northern California in hopes of finding a family nest that is conducive to peace and love. At this point, her citizenship secured, the young woman can be identified as Clarissa; she and her nine-year-old son, Joe, who has joined her and McBride in the U.S., are the sound crew for the film, which documents their long cross-country odyssey. Clarissa, who is now pregnant with Jim's child, provides voice-over narration to fill us in on their adventures. As they hole up in cheap motels, deal with car and camera breakdowns, and sometimes bicker like a family or just watch the vast American landscapes roll past, we experience along with them the real meaning of the "dropping out" and "finding yourself" associated with the period. There is, to be sure, a degree of dope smoking and a relaxed attitude to child-rearing and sexuality, but this is not just a free-love drug party, it is a serious journey and search, however naive it may seem, for a good, fair, healthy way to live, which involves at least its share of unglamorous drudgery and boredom. The film ends, casually but movingly, on the birth of Clarissa and Jim's child and their at-least-for-now decision to give life as a family a go in the rural hippie enclave of Hyampom, California.

At only eight minutes, the rather more slick, shot-on-digital-video My Son's Wedding to My Sister-in-Law, from 2008, is a very brief catching-up on what has happened in the intervening decades--more of a nicely done commemorative wedding/family reunion video than a work of cinema. Clarissa and Jim split up not too long after Pictures from Life's Other Side took place, the kids grew into adulthood, and the convolutions of their extended family tree have led to the unusual situation described in the title. In the context of the other films, this one is rather slight; there's nothing particularly wrong with it, and it has some clever if somewhat glib editing, but the depth, breadth, and style of the preceding works may make you wish that McBride had found the time, energy, and/or resources to go deeper, the way he used to do when he was an idealistic hippie.

FINAL THOUGHTS:What a remarkable, valuable act of preservation is Lorber's blu-ray release of David Holzman's Diary. Taken together, the several Jim McBride pictures compiled here work together as a series of complementary aesthetic achievements, truly deep, nuanced, and thoughtful documents of their era, and proof positive that "personal"/"confessional" cinema can be of real interest and free of self-indulgence. When done right, such personal efforts can be aesthetically and thematically rich, nothing at all like being forced to watch someone's limited-interest home movies, which is what this kind of filmmaking can become in the wrong hands. McBride may have gone on to do a David Holzman of his own by very unwisely remaking Godard's Breathless with Richard Gere in 1983; but at the period represented on this release, his work was vital, fresh, and committed. It easily places him in the rarefied company of other American filmmakers also emerging at the time--Cassavetes (Faces), DePalma (Hi, Mom!), Downey, Sr. (Putney Swope), Coppola (The Rain People), etc.--who were part of a seminal wave of American filmmaking, creating cinema whose actual independence and intelligence anticipated the Golden Age of American film in the '70s and reminds us, in an age when we seem to call everything "indie," of what it looks like when a filmmaker uses their independence to stretch the bounds of the form, challenging themselves and us. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||