| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

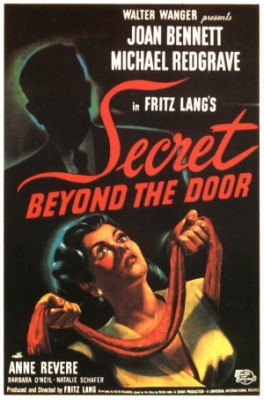

Secret Beyond the Door..., The

It must have put director Fritz Lang into an awkward position -- that of the innovator having to play the copycat -- when he saw fit to take on Silvia Richards's derivative, pale-imitation-Hitchcock screenplay for his 1947 film, The Secret Beyond the Door...; fortunately, the great German expat, who had managed to resurrect his career and reinvent himself with aplomb in the U.S., was coming off of two artistic triumphs, 1944's The Woman in the Window and 1945's Scarlet Street, so nobody could judge him on the basis of Secret Beyond the Door... alone. Lang's lead in both of those excellent films, the very versatile star Joan Bennett, reappears here and, along with costar Michael Redgrave (The Browning Version), does her level best to prop up the film's rather droopy, convoluted tale of suspense. But Lang's third time with Bennett, though not a flat-out failure, is not exactly a charm, either, and the gameness of the cast, along with many impressive traces of Lang's unmistakably stylish imprint, cannot entirely rescue the picture from its not very rigorous, secondhand and second-rate Hitchcock impersonation.

Richards, working from a short story by Rufus King, gives Lang a script that is a hodgepodge of updated Bluebeard legend (strangely alluring, murderous man punishes his wife's unwise curiosity about forbidden spaces in their castle), Hitchcock's grand Rebecca (the deep, mysterious emotional and psychological legacy left behind by the dead wife haunts and terrifies the new one), and the worst, least convincing, clumsily announced, dimestore-psychology parts of Hitch's Spellbound. Celia Barrett (Bennett), an independent NYC rich girl whose parents are long dead, loses her guardian angel, her brother, Rick (Paul Cavanagh), and, left alone in the world save for a fluttery socialite friend (Natalie Schafer, instantly recognizable as Gilligan's Island's future Mrs. Howell), she flees the marriage proposal of her attorney, Bob (James Seay), and heads off for a post-funeral getaway to Mexico. While witnessing a bit of lusty village violence (two men knife-fighting over a woman) that threatens to encompass her both literally and emotionally with its excitement, her newly bloodlust-tinged eyes catch those of a fellow tourist, the architect Mark Lamphere (Regrave), who seems to recognize her deep, unsettled passion. Despite his troubling, half-kidding misogynistic theorizing, Celia is attracted to this strange man, and his near-frightening passion is somehow easily able to convince her to accept the same proposal from him that she rejected from the safe, stable Bob.

We know from the beginning of the film that this will be an unusually troubled union, however. The first thing we see (after some tantalizing opening credits that make dream-like, surrealist promises that are never followed up on) is Celia approaching the altar of the Mexican village's disconcertingly ancient, ritualistically intimidating Spanish Catholic church to say her vows, her voiceover telling us of the titillating terror she, a confirmed bachelorette who never had any interest in marriage, feels at taking this reckless plunge (her life in New York leading up to Rick's death and her trip to Mexico are then played out as a flashback that makes up the first third of the action). Celia was right: That very night, Mark, with a strangely changed, too-stoical demeanor, tells her he must leave her to attend to some business. His vagueness makes her suspicious, and her suspicion becomes paranoia after she decides to forgive this frighteningly mercurial new husband whom she does, after all, love. She heads to her new home, a mansion in rural New York State run by Mark's briskly capable sister, Caroline (Anne Revere), who catches Celia up on some important tidbits her brother has neglected to tell his new wife, such as his being a widower with a prepubescent son by his late wife.

Celia's new home is a place that, like Rebecca's Mandalay, is haunted by some dark, violent secrets, disturbingly enigmatic hints about which are offered by its residents: There's Caroline, then a nanny/secretary (Barbara O'Neil) kept on out of guilt because one side of her face, which she covers with a scarf, was burned in a household accident; and finally, the boy, David (Mark Dennis), who's a creepy, overly formal miniature grownup who mourns his mother bitterly, hates his father, and has a personality that suggests his spiritual home is in The Village of the Damned. There is a special wing of the house that Mark has devoted to his hobby, which he shared with Celia while on their honeymoon: His architect's avocation is to rebuild historical rooms down to the last detail, searching out and buying all the original materials to make his recreations authentic. What he hasn't told her is that each room was the historical setting of some horrible wife-murder he's obsessed with; worse, there's one particular room, locked, that she and everyone are forbidden to enter. This is the door beyond which lies the secret of the title, and it promises to be anything but a pleasant surprise for the broiling-with-curiosity Celia, who cannot resist the allure of the forbidden and who ends up risking her life and her sanity because of her unfathomable, passionate love for the kind, tender Mark who alternates with the zombie-like, ice-cold, unrecognizable version.

It's fair to say that the convoluted, nonsensical, and incoherent revelations and explanations concealed behind that door are disappointing after what does manage, in Lang and company's capable hands, to be a convincing buildup. The film stumbles, hastily and clumsily, toward its ending under the weight of far too many elaborate twists and extraneous hints, tying up its big mysteries in a way so banal and obligatory as to make them seem inconsequential, and just barely collapsing over the finish line to conclude with a desultorily tacked-on, unsupportable happy ending for which there's simply no justification. The most glaringly bad parts are the moments where Bennett's voiceover runs down the points of the film's half-baked narrative logic, or a party guest suddenly announces that she happens to be a student of psychology and holds forth on all the supposedly Freudian mechanisms at play in Mark's obsessions. In both of these cases, what's being said is so baldly, clunkily expository that the actors might as well look straight into the camera and address us directly as script-summarizing stand-ins; even then, the verbalized theorizing would remain incredibly banal, half-baked (at least Spellbound let its ridiculously oversimplified take on "psychiatry" stay somewhat more implicit), and delivered too flatly and patly to let us even come close to suspending our disbelief for these explanations and how conveniently brought up or happened upon they are.

So, if The Secret Beyond the Door... is narratively so handed-down, faded, faltering, and unsatisfying, why is so much of it such a pleasure to watch, involving us in spite of ourselves and allowing us not to feel that the dull-witted denouement ruins the film irretrievably? Chalk it up to an overqualified creative team that's noticeably better than the material and manages to elevate it wherever possible. Bennett is, as usual, a stunning and charismatically convincing presence, and even the creakier lines she has to read in her narration can seem evocative when enunciated in her longing, dreamy "inner-voice" whisper; she also has an appealing, nicely physical onscreen rapport/chemistry with Redgrave, who is eminently capable of subliminally imparting both cold, brittle aloofness and jovially handsome tenderness. The film's real richness, though -- what makes the buildup so memorable and enjoyable for its own sake, regardless of the letdown in the "payoff" -- comes from the stunning making and moving of images that Lang, cinematographer Stanley Cortez, and editor Arthur Hilton (who also very smartly cut Robert Siodmak's The Killers) engage in. (This is one case where you actually wish the "substance" would stop getting in the way of the style, which is to say that it would've been nice if the script had been more deserving of visual realization this inspired, sometimes ecstatically so.) The lush elegance of the camera's movements; the inexorable emotional tension and suspense built in many scenes through Hilton's montage; the way Cortez and Lang have subtly contrived to block, frame, and light for Bennett to stand silhouetted against a window in a dark room or be framed within the frame as she ascends a staircase and pauses, encircled by the eerie masks and relics on the wall behind her; the long, long shadows cast by lightning through huge windows as a dark and stormy night rages outside; and, in a visual touch that takes your breath away, the complete darkening of the entire screen for a bold number of seconds as Mark and Celia are locked in at a crucial moment, only to have the blackness pierced by the abstract-looking cracks of light that appear from the other side of the door, which is buckling away from its frame as Mark smashes against it to get them out.

Regarded solely in terms of plot, The Secret Beyond the Door... mostly veers between the mediocre, the pointlessly tangled-up, and the just plain dumb; it's hardly a masterfully concocted story. But, as shown by the few examples cited above and many other bright spots throughout, it's in the telling, not the story, that we can feel, gratefully, that we're in the hands of a master who's making the very most of the inferior raw materials he's been stuck with. It's in Lang's steadfast refusal to shirk his duty to spin a captivating, sharp, layered yarn -- his insistence on going down with this ship, and making it look good in the process -- that the not-inconsiderable pleasures of this deeply flawed but nevertheless worthwhile picture lies, making it considerably more involving, intelligent, clever, and stirring than it really should be, a salvage job respectable enough that it's no surprise it was performed by a filmmaker who still had plenty of creative life and at least one more truly great picture (1953's The Big Heat) left in him.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

Olive's Blu-ray release of The Secret Beyond the Door..., an AVC/MPEG4, 1080p presentation of the film at its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1, is very good. Certainly, more restoration could have been done for a cleaner image; however, the source materials used are in more than decent shape, so the slight print wear (scratches/debris, occasional flickering and visual pops) are only mildly noticeable and never a distraction. The image is appreciably sharp and clear, the contrasts of Cortez's black and white compositions in good condition, and digital noise reduction does not appear to have been overused, so the retained celluloid texture allows for a nicely cinematic experience of the film.

Sound:The DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 soundtrack, maintaining the film's original mono, is also mostly unproblematic. There does seem to be some kind of imbalance between Joan Bennett's voice-overs, some of the dialogue, and louder noises, leading to stretches that are too soft and then suddenly shattered by a loud scream or burst of music. This may be more a function of the film's actual, innate soundtrack rather than attributable to those responsible for the audio presentation here, but either way, it ends up being one of those finger-on-the-volume-button deals in order to keep things audible but not deafening from moment to moment.

Extras:None.

The last and, by a significant measure, the least of director Fritz Lang's '40s collaborations with actress/muse Joan Bennett (which, to be fair, scaled such magnificent heights Scarlet Street and The Woman in the Window), 1947's frequently silly, sub-Hitchcock The Secret Beyond the Door... nevertheless has its Langian enticements to lure us in. For virtually every predictable yet implausible additional plot twist/dead end or bit of tediously expository dialogue, there's some redeeming example of Lang's famous style (courtesy the always visually enthused and imaginative director's working in conjunction with legendary cinematographer Stanley Cortez (The Magnificent Ambersons, The Night of the Hunter)), or some miraculous conviction and presence on the part of stars Bennett and Michael Redgrave, to salvage things. No good cinema aficionado would want The Secret Beyond the Door... to be anyone's introduction to Lang (between his silent/German period that gave us Dr. Mabuse the Gambler and Metropolis and his remarkable American second act, when he made everything from the aforementioned classics to Fury to The Big Heat, there's at least a dozen superior candidates for that), but anyone who has already become enamored of Lang's inimitable way of creating a richly atmospheric, evocative, ominous world onscreen will find plenty to appreciate and admire here. The film is clearly one of this master's minor works, but it also reminds us that the cinematic constellation of Lang contains no star, however tiny or however weakly it shines, that should be left entirely unexamined and unexplored. Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||