| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Hard Times (1975, Sony Choice Collection)

"I suppose you've been down the long, hard road."

"Who hasn't?"

A mythic fantasy...shot in laconic, bare-knuckled, tough-as-shoe leather style. Sony Picture's Choice Collection line of hard-to-find cult and library titles has released Hard Times, the 1975 box office hit actioner from Columbia Pictures, starring Charles Bronson, James Coburn, Jill Ireland, Strother Martin, Margaret Blye, Michael McGuire, Felice Orlandi, Edward Walsh, Bruce Glover, Robert Tessier, Nick Dimitri, and Frank McRae. The smashing directorial debut of screenwriter Walter Hill, Hard Times' quintessential 70s "buddy picture" format starring "The Streetfighter With No Name" and his fast-talking bankroll, eschews all the cutesy-pie bullsh*t of that subgenre and strips down its Western-inspired fable of survival in Depression-era New Orleans to the barest essentials--with exhilarating results. No extras for this very nice stereo, anamorphically-enhanced widescreen transfer.

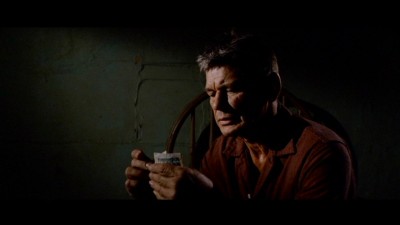

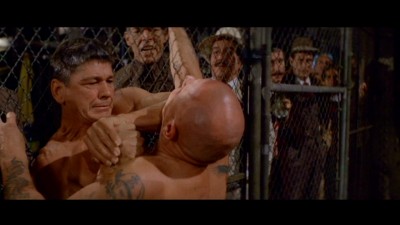

Louisiana. The Great Depression. Drifter Chaney (Charles Bronson) hops off a train and makes his way towards the city. Drinking coffee at a diner late at night, he spots a large group of men filing into a warehouse. There, he silently watches as an illegal bare-knuckled fight is quickly organized by flunky Caesare (Maurice Kowalewski) and fast-talking gambler Speed (James Coburn). The odds are called out, bets are taken, and the brutal fight begins, but Speed's hitter (Chuck Hicks) loses. Grabbing something to eat at an oyster bar, Speed is confronted by the laconic Chaney. Chaney doesn't want the dismissive Speed to bankroll him in a fight; Chaney has all of six dollars to his name, and he wants Speed to bet it for him--on himself. Going back to the warehouse, Speed does just that, along with a $150 of his own money, which he promptly doubles when Chaney knocks out Caesare's hitter with one powerful blow. Traveling together to New Orleans, Speed has big plans for Chaney, but Chaney plays it cool, wishing to get the lay of the land before committing to a partnership with the unsteady Speed. Renting a squalid, empty room, Chaney waits, eventually meeting the equally wary Lucy Simpson (Jill Ireland) at a greasy spoon. Going against her expectations, Chaney is friendly but tentative with the married, unemployed Lucy (her husband is in jail)--a situation that doesn't seem to please her anymore than if he had come on strongly to her. When Chaney visits Speed and agrees to a temporary partnership, Speed recruits Poe (Strother Martin), a drug addict and failed medical student, as Chaney's cut man. Complications arise when Speed has to raise a large sum of money from loan shark Le Beau (Felice Orlandi) to buy-in a fight with cannery owner and big-league gambler Gandil (Michael McGuire). Cagey Gandil smells a hustle, and further ups the buy-in, forcing Speed to organize a fight down in Cajun country. Beating Gandil's top hitter, Jim Henry (Robert Tessier), only makes things worse for Chaney and Speed, particularly when Speed blows Le Beau's pay-off money, and Gandil vows deadly revenge for losing face.

I was lucky enough as a little kid to see Hard Times when it first came out, on a double bill at the drive-in with an earlier Bronson epic, The Stone Killer. For the life of me I can't remember too much about that 1973 crime meller, but 1975's Hard Times stayed with me as one of those experiences at the theaters you only understand later as being highly influential on how you see movies in your adulthood. Brutal and exhilarating, and yet still kid-friendly with that PG-rating (very little blood, and no nudity), Hard Times seemed to my 9-year-old brain to be a dark comic book come to life: primitive in tone yet surprisingly sophisticated in execution, and of course, kinetically exciting. And for a good 15 to 20 years or so after it came out, director Walter Hill could routinely be counted on to deliver top-notch action outings like The Driver, The Warriors, The Long Riders, Southern Comfort, 48 Hrs., Extreme Prejudice, Johnny Handsome, Trespass, and Last Man Standing, a few of which today (certainly The Driver and The Warriors) can genuinely be considered influential within the genre.

From what I've read, the germ of Hard Times originally came from a Western script Hill wrote, entitled Lloyd Williams and His Brother, that Sam Peckinpah at one point wanted to direct, after helming Hill's script for Steve McQueen's blockbuster, The Getaway. After the success of that picture, and Hill's subsequent high-profile scripts for two less-successful Paul Newman actioners (John Huston's The Mackintosh Man and Harper's sequel, The Drowning Pool), Hill was approached by producer Larry Gordon to work on a story about contemporary streetfighting in California. Hill suggested making it a Western, using parts of his Lloyd Williams script, but Louisiana native Gordon changed the setting to Depression era New Orleans, giving Hill the chance to direct his own screenplay if Hill would work for scale. Limited to a tight budget, Hill originally envisioned then-hot property Jan-Michael Vincent and Warren Oates in the leads, before money was bumped up to hire James Coburn and Charles Bronson, who was that year's fourth most-popular actor at the box office (certainly Bronson's peak in terms of yearly U.S. rankings). Shooting on a quick 35+ day schedule, The Streetfighter, as it was to be released (and as it's still known today overseas), was quickly renamed back to the script's original Hard Times title (to avoid confusion with Sonny Chiba's 1974 martial arts hit, The Streetfighter), and released in theaters in early October, 1975. On a reported budget of 2.8 millions (still relatively peanuts), Hard Times reportedly returned rentals of over twice that, making it a solid--if not Death Wish-sized--hit for Columbia.

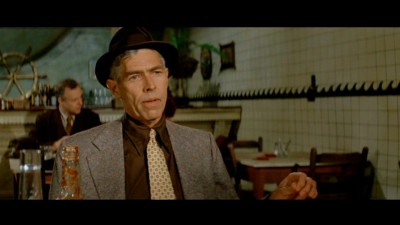

I haven't seen Hard Times in years, but what resonates now with me in the movie aren't the celebrated fistfights--as thrilling as they were to a pre-MMA 9-year-old back in '75--but rather Hill's carefully-applied realistic, gritty facade over what's essentially a fantasy, a movie fable with one nasty message: survival at all costs. So many reviewers and critics of Hard Times make a connection between the movie's grungy, believable Depression-era settings and Hill's hard-boiled, stripped-down storytelling approach as indications, somehow, of the movie's objective, non-romantic core. However, if you can get past the satisfyingly downbeat surface of this hardscrabble production, you see an actioner that's far more pulpy "poetry" than "neo-realism." Hill's fairy tale sleight-of-hand is everywhere here, creating a dream-like narrative that has little to do with the true realities of his story's nominal setting or characters. The visual schematic may initially suggest an appropriately down-on-its-luck verisimilitude, but quickly one sees how Hill has cinematographer Philip H. Lathrop frames his scenes in a non-realistic, presentational, painterly way (Bronson at the diner, for instance, looks like something out of Edward Hopper). As for the characters, they seem to exist without preamble, nor is Hill interested in providing them--or us--any further grounding. Bronson's Chaney not only divulges no information about his past or future, he literally comes and goes like a ghostly specter--albeit a ghost with a left hook worthy of a mule kick--riding into town in a darkened boxcar and frequently disappearing into the shadows whenever he skips out on his troublesome relationships (when he first meets Coburn, Coburn turns around at the oyster bar and sees Bronson already sitting at his table, as if Bronson materialized out of thin air). In Hard Times, we have a dope addict--a claimed descendent of that most romantic of poets, Poe--that doesn't take dope once he's flush with money again, but rather spouts poetry ("journeys of the imagination," Strother Martin calls his off-camera activities), as well as a loan shark strong-arm who is serious enough in his business to advise Coburn to sell his sister if he has to, to pay his debts...but then doesn't touch a hair on Coburn's head.

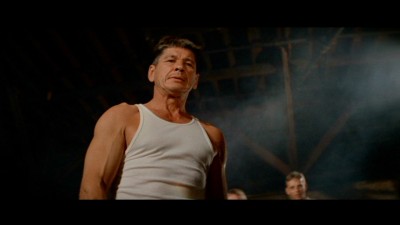

Of course the most obvious indications that we're watching a story for "movie children" are Hard Times' most celebrated (and rightly so) moments: the fistfights. Beautifully choreographed ballets (real fistfights never look--or feel--this fun), Bronson and his opponents pummel each other over and over again with superhuman blows and kicks (the effects sound like tree trunks slamming into concrete), with nary a trace of blood until the final fight, where Bronson is finally allowed a small cut on his face. No one's hand is smashed, no one starts pissing blood, no one's face is cut to ribbons, no one's head swells up to the size of a balloon (trust me, that's what happens...). The fights in Hard Times that all the critics call so realistically exciting, are as realistic as a Looney Tunes cartoon, where Sylvester gets flattened by an anvil only to spring back to normal in the next frame. Perhaps most allegorical of all the elements in Hard Times is its celebration of its curious mix of Hemingway professionalism and Howard Hawksian appreciation for manly professionalism, by way, it seems, of Damon Runyon's almost comically well-behaved criminals. In Hard Times, this colorful underworld of gamblers, hitters, loan sharks, leg breakers and prostitutes operate on a chivalrous code of conduct that is about as realistic as the fight scenes. Why would Chick Gandil spot Speed a $100 bet, when competitor Speed doesn't pay his debts? Why would lonely "good guy" Chaney keep his distance from Lucy, when she's asking for sex he won't give her (nothing in the movie ever indicates they consummate the relationship)? Why would a no-holds-barred knuckler like Street refuse lead fist weights in order to beat Chaney, the guy currently kicking his ass? Why would arm breaker Bruce Glover smile when needling dick Speed gets off scot free at the end...and for that matter, why does Glover's boss, Gandil, extend a friendly camaraderie to Speed and Chaney, the man who humiliated Gandil, and very probably toppled him from his power position in New Orleans as a result (in the best Hawksian manner, Gandil appreciates Chaney's proficiency and offers, "It's been a pleasure watching you work," with a sincere smile)? Interestingly, the only criminal who truly behaves like a criminal is Cajun welsher Pettibon (Edward Walsh), who, it is suggested, acts thusly because he's "backwoods," and thus, uncivilized (Poe warns, "These boys are not refined,"). All of this is hardly "realism," but rather romantic myth-making set down in a squalid setting (even Hill's haiku-like dialogue sounds poetically abstract).

That contrast between fantasy form and hardscrabble content comes to full fruition when Hill gives you Hard Times simple message: times are hard, and you have to survive anyway you can. And to survive the Depression, you need to make money: with Bronson, it's with his fists; with Ireland, it's with her body; and with Coburn, it's with his fast-talking mouth. The "phony" sentiments of Hill's honor-bound gamblers and hitters is contrasted by this stark reality. No doubt if Hard Times was made today, we'd have to slog through a bunch of blather to more clearly "understand" Chaney's "journey" and why, oh why, he has to fight. But Hill is having none of that. We don't even know if Chaney has ever fought before for money, let alone for what purpose he really needs the money (he sure gives enough of it away at the end, when before he told Poe, "Money's hard to come by,"). Hill's explanation is brief and to the point...and devoid of any chance for misinterpretation. Ireland asks Bronson what he does for money, and he responds, "I knock people down." She asks how that makes him feel, and he responds, "It makes me feel a hellava lot better than it does him." When pressed for a reason, he ends the discussion with, "Hey, there's no "reasons" about it--just money." Money in the Depression equals survival. And Chaney is going to survive (we get no further explanation for Lucy's or Speed's actions, either: she takes another man because he has a steady job, and Speed gambles away his money because he gambles away his money, with no attempt at explaining why).

As for the performances in Hard Times, they're balanced out nicely within Hill's aesthetic. By this point in 1975, career positions had switched for Coburn and Bronson. Co-stars of lower order in Sturges' The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape, Coburn then went on to brief A-list status in the late-sixties when his Derek Flint spy franchise took off, before box office misfires like Duffy, Hard Contract, Last of the Mobile Hot Shots, The Carey Treatment, The Honkers, and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid permanently cooled his leading man status. Bronson, however, languished during the 1960s on television (The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters and guest spots on shows like Combat! and The Fugitive) and in undistinguished supporting roles for big films like The Sandpiper, Battle of the Bulge, and The Dirty Dozen, before going off to Europe and becoming a phenomenon with international audiences with movies like Farewell, Friend, Once Upon a Time in the West, Rider on the Rain, Cold Sweat, and Red Sun (in 1971, he shared the "World Film Favorite--Male" Golden Globe with Sean Connery). By 1975, he was ranked just behind Robert Redford, Barbra Streisand, and Al Pacino at the U.S. box office, so he clearly was in the driver's seat for Hard Times, a position inevitably reflected in the movie's performances. Coburn, looking hungry and nervous, has to play to Bronson's character; he needs Chaney more than Chaney needs Speed...and the same probably went for Coburn and Bronson. It's a good turn for the talented Coburn, with plenty of ironic flashes of that toothy grin hiding a wise-assed game-player who doesn't always know when it's best to keep his shut his mouth. It's difficult to assess Ireland's performance here because apparently, quite a bit of it was cut from the final print, much to the consternation of her husband--Charles Bronson (apparently, that created a rift with Hill that resulted in no further collaborations, unfortunately, with Bronson). However, her dulled, neurasthenic approach to the character is interesting; it's just a pity we're never quite sure when she's going to pop into the movie next (which, overall, actually works within Hill's purpose here). As for Bronson, this is certainly one of his best performances, and not just a trick of Hill's editing. Bronson's eyes say a lot here--mostly an unspoken sorrow even for the men he's beating up--while his physicality during the fight scenes is astonishing. Giving his official birthdate as 1921, making him around 54 during Hard Times' filming, readers of Bronson's frequent collaborator director Michael Winner's autobiography, Winner Takes All, will know that it's quite possible--according to Jill Ireland herself--that Bronson may have been a good eight years or more older than his "official" age (she stated Bronson kept his real age secret for fear of losing work). In other words: what looks like a hard-assed ballbuster in his mid-fifties may actually be the same-said peak-conditioned senior citizen Bronson...in his early sixties. Remarkable. Somehow that makes his turn here in Hard Times even more believable in this fairy tale sprinkled with grimy soot: Bronson the senior citizen wasn't going to relinquish an inch no matter what his real age may have been; he was going to survive. No wonder Bronson smiles when his first opponent offers, "Hey, Pops--you're a little old for this, ain't ya?"

The DVD:

The Video:

Hard Times' anamorphically-enhanced, 2.35:1 widescreen image looks terrific, with a sharp, sharp image, solid color valued correctly, acceptable grain, and respectable fine detail. Very few screen imperfections that I could spot. Looks better than I ever saw it, on VHS or the big drive-in screen.

The Audio:

Sounds like a Dolby Digital English stereo Surround track to me, with little or no hiss, and a booming re-recording level--wild for one of these Choice Collection titles. No subtitles or closed-captions.

The Extras:

No extras for Hard Times.

Final Thoughts:

Movie realism...in other words, wonderfully, even poetically "fake." There's a fairy tale of honorable gamblers and ethical streetfighters hiding in Hard Times' grungy story of Depression-era desperation, where the gritty facade fabricated over the fable by screenwriter/director Walter Hill, only heightens the story's central message: you gotta fight to survive any way you can. One of the best examples of action filmmaking from any decade, with a remarkable contrast of style and purpose. Even without any bonuses, on content alone, Hard Times gets DVDTalk's highest award: the DVD Talk Collector Series ranking.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published movie and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||