| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

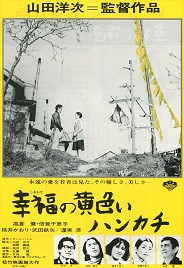

Yellow Handerkerchief, The

He's best known for the long-running "Tora-san" film series, comedy-dramas starring Kiyoshi Atsumi, which lasted a remarkable 48 theatrical feature films from 1969 to 1995, ending only with Atsumi's death in 1996. Yamada made other movies before, during, and after, of course, with the Oscar-nominated The Twilight Samurai (Tasogare Seibei, 2002) ironically (considering he almost never makes samurai dramas) receiving the widest release of all.

The Yellow Handkerchief (Shirawase no kiiroi hankachi, "The Yellow Handkerchief of Happiness," 1977), sandwiched between the two Tora-san movies Yamada also made that year, made less money than those but swept all the big Japanese film awards. It won the Best Film prize from the leading film magazine, Kinema Jumpo, and won virtually every category in which it was nominated at the Japanese Academy Awards, including Best Film, Best Director, Best Screenplay, and all four acting categories. It's high regard led to two theatrical remakes, including a misbegotten American version, and multiple television adaptations, including one supervised by Yamada.

The picture fuses Yamada's strengths as a humanist storyteller with movie star Ken Takakura's hard-boiled screen persona. It has elements of Yamada's "Tora-san" movies (with Tetsuya Takeda's character notably Tora-san-esque) but also plays like a long-overdue epilogue to Takakura's phenomenally successful (yet still unseen in the U.S.) "Abashiri Prison" movies of the 1960s.*

After receiving a Dear John letter from his girlfriend, distraught, immature and garrulous young Tokyo factory worker Kinya Hanada (Takeda, making his screen debut) abruptly quits his job and buys a red Mazda Familia, driving it onto a ferry bound for Hokkaido, Japan's rural northernmost main island.

There, he crudely picks up vulnerable traveler Akemi Ogawa (Kaori Momoi), a train hostess pushing food carts up and down aisles, likewise heartbroken after a recent breakup with her cheating boyfriend. They have little in common, except desperate loneliness.

A third wanderer joins them, reticent and mysterious Yusaku Shima (Ken Takakura), a former coal miner newly released from Abashiri Prison after serving a murder conviction. In a wonderfully underplayed little scene without dialogue, the newly released ex-con wanders into a restaurant and is quietly overcome with emotion drinking his first bottle of beer and eating his first bowls of ramen and katsu-don in years. (Takakura reportedly didn't eat anything for two days prior to shooting this scene to lend verisimilitude to the moment.)

(Mild Spoilers) In flashbacks, Yusaku's backstory is gradually unveiled. A shy but troubled miner, he found meaning in his life marrying lonely supermarket cashier Mitsue (the luminous Chieko Baisho), despite living in poverty in a virtual tin shack near the mine. After she miscarries, he gets drunk and has a run-in with a couple of young thugs, killing one, resulting in his conviction. He sends her a postcard upon his release. If she wants him back he instructs her to hang a yellow handkerchief on a pole outside their home (used for Koinobori, signifying male children during the Tango no sekku holiday), as she'd done years before to signal to him her pregnancy. Yusaku, however, assumes Mitsue wants nothing to do with him now. She likely remarried and probably doesn't even live there anymore.

Calling The Yellow Handkerchief a "road movie" does it a kind of injustice because it's so much superior to nearly all movies falling in that category. Mainly, it's a touching drama with wonderfully funny comic vignettes about three very different people drawn together by circumstance and their own soul-crushing unhappiness and uncertainty about their futures.

Kinya is impulsive and crude. Like Tora-san he tends to say the wrong thing at the wrong time, and rarely stops talking. He sees Akemi as easy pickings as she's on the rebound, but at the beginning of the story she's clearly in no shape for romance or anything else, and her depression is as suppressed as his is obvious. In contrast to these 20-somethings, middle-aged Yasaku is circumspect, socially conservative with a traditional rural politeness and formality that clashes with their urban brashness and pseudo-stylishness. (One of the film's few flaws is how often Yasuku keeps begging off their offers to drive him back to where Mitsue may still reside. His desire not to impose himself upon them is repeated a bit too often.)

The authentic emotional pain these characters feel is delicately offset by many funny and/or eccentric moments. Kinya treats his new friends to expensive locally caught crab only to suffer an extreme allergic reaction: sudden attacks of diarrhea, not good in Hokkaido where rest stops are few and far between. As he often did in Yamada's non-Tora-san films, Kiyoshi Atsumi makes a cameo appearance, here as a sweet-natured police chief who calmly bails Yasuku out of a tense situation after the parolee is caught driving without a license. Other regulars in Yamada's "Tora-san" films likewise appear here in small roles. (Hisao Daizai as a Japanese inn owner, Chieko Misaki as a woman crying at the police station, etc.)

The story was suggested by a 1971 New York Post column called "Going Home" by Pete Hamill, about college students on spring vacation meeting an ex-con in Georgia, and to some extent the apparently unrelated 1973 song "Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree," each inspired by folk stories dating as far back as the Civil War. Apparently actress Baisho heard the song first, and then suggested the idea to Yamada, who found Hamill's essay.

Yamada has a fondness for rural Japan, areas long in decline with the urban migration Japan has faced since the early postwar days. His equally fine A Distant Cry from Spring (1980), also with Takakura and Baisho, is likewise set in Hokkaido, while many others take place on Japan's myriad small island communities. He and his late, longtime cinematographer Tetsuo Takaha, extol the beauty of these largely forsaken places while celebrating the enduring spirit of the people who choose to remain there, most obvious here when the trio, their car unmovable after an accident, are invited by a farming family to spend the night in their home.

Video & Audio

Twilight Time's release of this Shochiku-owned title, limited to 3,000 units, looks very good. At the time most Japanese filmmakers were switching to 1.85:1 widescreen after years of using outdated ‘scope lenses, but Yamada had enough pull to shoot most of his films from the early ‘70s on in 2.35:1 Panavision. The transfer is sharp with good color, while the 1.0 DTS-HD Master Audio is strong. The English subtitles are a bit lacking, selectively translating secondary dialogue of various passersby and lyrics from pop songs from the car radio. It's a minor complaint, more obvious in the early scenes than later on when the story becomes increasingly intimate, but a more complete translation would help.

Extra Features

None, other than Julie Kirgo's usual liner notes.

Parting Thoughts

I think it was Los Angeles Times film critic Kevin Thomas who described Yamada's films as "sentimental in the good sense." His films earn their sentiment with honest, often ugly and chaotic emotion, from troubled characters who don't really know how to deal with their emotional anguish and confusion. The Yellow Handkerchief is an excellent example and a DVD Talk Collector Series title. Here's hoping it does well, because releases of so many other films by Yamada, particularly Home from the Sea (1972), A Distant Cry from Spring, and the Tora-san series are long overdue.

* There's even a neat reference to Keisuke Kinoshita's classic film Carmen Comes Home (1951).

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian largely absent from reviewing these days while he restores a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||