| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

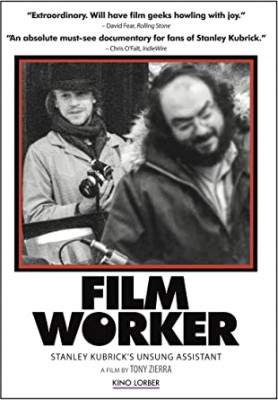

Filmworker

Kurosawa had his disciples, like Teruyo Nogami, devoted follower and trusted assistant beginning with Rashomon (1950), still devoting much of her life to the long-dead director, even into her nineties. Harry Carey Jr., a member of John Ford's stock company, was one of dozens who loved the man even though he was, frequently, a cruel sadist. Gary Graver, Orson Welles's trusted cinematographer for the last 15 years of that filmmaker's life, almost literally gave his life to Welles. And then there was, and happily still is, Leon Vitali, indispensable right-hand man to Stanley Kubrick and the subject of the riveting documentary Filmworker (2017).

Directed by Tony Zierra, the film offers many surprises, not the least of which is the relative absence of Kubrick himself. Though he's often seen in video and film clips mulling about the periphery, his voice is heard only infrequently; we probably hear more of Vitali's imitation of Kubrick than from Kubrick himself. Posters for the film cleverly focus on Vitali, in the background while Kubrick, in the front, is out-of-focus.

Born in England, Vitali (b. 1948) started out as an actor, busy on the stage and in British television, on shows like Z Cars and The Fenn Street Gang, often playing working-class villains, though he frequented sitcoms also, and co-starred with Martin Sheen and Michael Gambon in the TV-movie Catholics. Like most everyone else, Vitali had been bowled over by Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and A Clockwork Orange (1971), and couldn't believe his good fortune when Kubrick cast him as Lord Bullingdon, Ryan O'Neal's bitter rival, in Barry Lyndon (1975), even if that meant O'Neal's Barry violently beating Vitali's lord mercilessly in take-after take.

During production, Vitali became fascinated with Kubrick's meticulous methods and perfectionism, and after expressing to him a desire to work behind-the-scenes, Vitali gave up acting when Kubrick asked him to help out in casting the role of little Danny Torrance in The Shining (1980). In no time, Vitali found himself tasked with everything obsessive workaholic Kubrick didn't himself have time for: running lines with actors, checking the color timing of prints, cleaning up after Kubrick's dogs and creating an elaborate video monitoring system for a terminally ill cat, checking the makeup on extras, signing off on video transfers and artwork (down to the millimeter) with VHS, laserdisc, and DVD labels around the world and, on rare occasions, pressed into small parts in Kubrick's films. And while undeniably a genius, Kubrick often left Vitali the thankless task of informing actors and others they'd been fired by a director too cowardly to face them himself.

Vitali worked insanely long hours, perhaps a hundred hours or more per week, fielding middle-of-the-night calls from Kubrick from his bed, which sometimes was a doormat on the floor of some office, where Vitali would often sleep in his clothes. Vitali might have been replaceable, but it would have taken 15 or 20 guys to do the same volume of often highly specialized work. He recounts the many people who'd effusively approach Kubrick with, "I'd give my right arm to work for you." Vitali's response: "Only your right arm? What about your left arm? What about the legs? The torso?" Funny as this is, he isn't kidding, nor was Kubrick, and there's no question Vitali for nearly half a century has given damn near every molecule of his own body.

Little remains, in the physical sense. The pressures of this devotion took its toll, even and indeed especially in the months following Kubrick's untimely death in 1999, leaving Kubrick's final work, Eyes Wide Shut (2000), vulnerable to studio tampering, with only Vitali and a few others to make certain it was released precisely according to Kubrick's wishes. Filmworker only vaguely alludes to how Vitali's devotion damaged his relationship with his family, or its physical toll. In new interviews Vitali looks like the drummer for a rock band who spent far too many decades on the road living it up. Partly for this reason, for many years after Kubrick's passing the sometimes nearly penniless Vitali was snubbed by industry insiders who once snapped to attention when he called, the movie equivalent of Moses handing the word of God.

At one point, Vitali remarks that he had to maintain a certain emotional distance from Kubrick, to allow the director to vent his spleen at Vitali with the understanding that Kubrick's screams and insults weren't really meant as personal attacks. Others interviewed for the film liken Vitali to a pitiful almost-slave -- he worked tirelessly yet often was not paid for his labors -- yet the film ends triumphantly, Vitali genuinely and rightly proud of his not-insignificant contributions to Kubrick's later masterpieces, and in preserving the great man's legacy exactly the way Kubrick would have wanted. In the end, Vitali comes off as an extraordinary hero of cinema.

Video & Audio

Filmed in high-def for 1.78:1 viewing, Filmworker looks and sounds great throughout. The picture includes clips from all of Kubrick's films from 2001 forward, and those look great, too. Optional English subtitles are provided on this Region "A" encoded disc.

Extra Features

Supplements include the usual trailer and, better, a Q&A with Leon Vitali and director Tony Zierra.

Parting Thoughts

An exceptional documentary, one of the best I've ever seen about dedication to a life in film, full of surprises, and every minute fascinating. A DVD Talk Collector's Series title.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian currently restoring a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||