| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

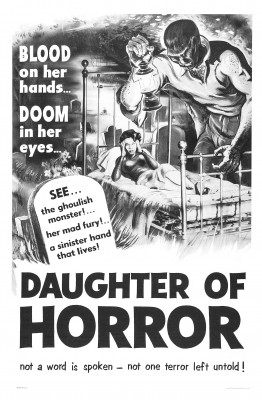

Dementia (1955) / Daughter of Horror (1957)

Dementia (1953), equally known under a later title, Daughter of Horror (a 1957 release), is a difficult film to describe. Originally conceived by writer-producer-director John Parker as an experimental short with no spoken dialogue, it was expanded to 58 minutes and played few theatrical bookings in 1953 and '55 before it was acquired by producer-distributor Jack H. Harris, who cut several minutes and added some narration by a young Ed McMahon, who is briefly, murkily glimpsed in added footage, at least it appears to be him. That version, Daughter of Horror, also had few bookings. However, scenes from the reedited Daughter of Horror turned up as the movie playing at the movie theater in the Harris-produced The Blob (1958). The identity of that film-within-a-film was a mystery for many years.

Then as now, critics and audiences are sharply divided about Dementia's merits. Advocates regard it as a fascinating expressionistic work of art ("the first foreign film made in Hollywood" said Downbeat magazine), while detractors see it as pretentious and boring. I first saw it, I think, on laserdisc nearly 30 years ago and didn't care for it then and still find it pretty excruciating viewing today.

Often described (and certainly later marketed) as a horror film, Dementia is mostly a clumsy pseudointellectual Freudian-type study, with expressionist and surreal scenes but stylistically patterned after the film noir genre. The plot, such as it is, concerns a young woman (Adrienne Barrett) who awakens in a skid row hotel. She then wanders about the seedy streets of Venice, many of the same locations later brilliantly used by Orson Welles in Touch of Evil (1958), eventually falling in with a pimp who sets her up with a fat rich man (Bruno Ve Sota, the poor man's Dan Seymour, who was the poor man's Sydney Greenstreet).

His slovenly, unseemly ways remind her of her own abusive father, whom she stabbed after he shot her mother, triggering her to, in turn, stab the fat man, who falls backward out a window to his death, clutching a pendant he ripped from her neck on the way down. The rest of the film follows the increasingly paranoid woman as she tries evading the police.

The movie has no spoken dialogue, which may have been an attempt to maintain a dreamlike atmosphere, and/or because its low budget precluded the additional expense to properly record synchronized sound. Regardless, the lack of any dialogue works some of the time while being painfully awkward and attention-drawing in other scenes. Probably made for less, perhaps a lot less, than $50,000, the film is somewhat impressive visually given its low budget, especially the cinematography of William C. Thompson, a veteran dating back to the early silent period, who by the 1950s was working for the likes of Ed Wood and other zero-budget filmmakers. Ve Sota in later years claimed to have directed large portions of Dementia and coached the inexperienced Barrett; he may have inflated his contributions to Dementia, but given his own later work it seems possible.

The picture's notoriety mainly rests on its multiple violations of the Production Code and other regional film censorship laws. That "the first foreign film made in Hollywood" crack by Downbeat isn't too far off the mark: during this period some small-time distributors were acquiring arty and mainstream French and other European movies not for their value as cinema but for their racy content (extra-marital affairs, fleeting nudity, etc.) and exhibiting them to the raincoat crowd in search of smut. (Actresses like Jeanne Moreau likely had more initial American exposure in such releases than her acclaimed and better-remembered work.) These releases often had terrible, sometimes unreadable subtitles or were badly dubbed, and the prints looked like dog meat. Dementia resembles those releases far more than anything emanating from Hollywood studios.

Some writers have read far more into Dementia than was probably intended, some hailing it as a "psycho-social critique" of endemic violence inflicted by men in a patriarchal society, but to me it's more likely jack-of-all-trades Parker was aiming for an arty, visually interesting but also commercial film, and surrounding "the Gamine" (as Barrett's character is called) with violence and threats of violence was a means to that end. Reportedly Parker based the film on Barrett's own nightmares, hiring the non-actress (she reportedly was his secretary) to act out those recreations. Parker himself was an Oregon-based movie theater chain owner.

One aspect of Dementia I don't recall reading anywhere is the possibility that, intentionally or unintentionally, Barrett's autobiographical visualization might be equally rooted in sexual orientation. Pock-faced and wearing no makeup, Barrett resembles a homely version of Claire Bloom's thinly-coded lesbian in The Haunting (1963); they even dress more or less the same. Little, indeed next to nothing is known about Barrett, who made no other films and seems to have vanished. This is not to say Barrett herself or the character she plays in Dementia was a lesbian, closeted or otherwise, but there are hints in the film that either or both might be true, even if not consciously intended by the filmmakers.

The film is interesting mainly for exposing a seedy side of "Hollywood" the entertainment industry was loathe to put on display in movie theaters. At the same time the film's semi-amateurish qualities occasionally manifest: in the flashback with the father (an apartment scene filmed in a "graveyard") a table lamp overheats and the lampshade nearing catches fire during this key scene. Later, as the terrified Gamine runs through the streets in terror, a happy-go-lucky puppy, anxious to join in the fun, merrily follows her in one extended shot.

Video & Audio

A Cohen Media Group release via Kino Lorber, this Blu-ray release touts a 2K digital restoration from the 35mm negative, and while the image is impressively sharp for the most part, as CineSavant notes in his review (a rave about the film, tempered by complaints about the disc), this release is missing Parker's director credit (except for a few stray frames) and a key shot present on earlier home video releases is inexplicably missing. The DTS-HD Master Audio mono soundtrack is fine, and the disc is region "A" encoded.

Extra Features

Supplements include the complete Daughter of Horror recut, mastered from far from ideal film elements, though it's entirely watchable and, indeed, in some ways plays better than Dementia; even McMahon's narration is moderately effective. A trailer for Daughter of Horror and restoration comparison are also included.

Parting Thoughts

Dementia is so unusual it deserves to be seen once; whether you find it fascinating or nearly unwatchable depends upon your tastes in the outré. Recommended.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian largely absent from reviewing these days while he restores a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||