| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Martin Scorsese\'s World Cinema Project No. 4 (The Criterion Collection)

Unlike 99% of reviews of DVDs and Blu-ray discs I write here, Martin Scorsese's World Cinema Project No. 4 is a boxed set most of us will approach with virtually no frame of reference. The six feature films in the set emanate from Angola (though made with French money and shot in Congo), Argentina, Iran, Hungary, India, and Cameroon. I've seen other Indian and Iranian films, but am hardly an expert of those country's cinemas, and never before experienced movies from the other four that I can remember. I'm also unfamiliar with the filmmakers behind them save Hungary's Andre DeToth, who eventually had an extensive career in Hollywood.

On the other hand, all but one of the films offer stories with universal themes of family relationships, love relationships, and most deal with issues of economic class and people in positions of power exploiting the nearly powerless. And even if one goes into these films completely unaware of the finer cultural and historical aspects, they have an educational function: what daily life was like for people living in poverty in Angola and Cameroon during the 1970s, for instance, or what kinds of movies audiences in 1930s Argentina and Hungary experienced, and what kinds of stories appealed to those audiences.

As such, this review will be more of a collection of random impressions of each film, what I liked about them and the cultural/historical aspects I found bemusing. Also, more than usual I'll refer to plot elements, characters, production values and styles relative to Hollywood and European films in hopes of providing the reader with something to compare them to, a better sense of what these movies are like. I can't say that any of the films shot up into my all-time 10 Best Films list but they were all quite interesting and, from my limited perspective, engrossing and enlightening, and Criterion's new boxed set is loaded with extras providing an absolutely essential service here: putting them all into cultural, historical, political, and (cinema) industrial context.

Kicking things off is Sambizanga (1972), set in 1961 Angola, then a colony of Portugal. John Henry-esque tractor driver Domingos Xavier (Domingos de Oliveira) works for a company that, like in old Hollywood prison films, sledgehammers little rocks out of big ones. He's happily married to Maria (Elisa Andrade), with whom he has an infant son. They live in a dirt-floor shack without so much as a kitchen table but are mostly happy and clearly in love. After discussing a pamphlet from anti-colonial nationalists, Domingos is dragged from his home, arrested, and disappears into a Portuguese prison where he's at risk of being tortured or killed.

The film, directed by Sarah Maldoror, cuts among three narrative threads: Maria's mostly on-foot journey to Luanda, her child in tow, determined to locate her husband's whereabouts; Domingos's experiences in prison; and a dramatization of the dissident network of young and old men, and even children, keeping tabs on the prison and their efforts to determine the identity of this latest arrest.

The film impresses in unexpected ways. There are scenes of dire poverty and oppression and, later, of torture, but none of this overwhelms the picture because Maldoror herself consciously refuses to dwell on that stuff, balancing it with happier, ordinary scenes of Angolan family life. Late in the film, for instance, there's a music festival populated by revolutionaries surreptitiously meeting there to discuss Domingos's case, but who also enjoy groovin' to the music. Indeed, the film for me is most interesting following characters going about their business: Maria slowly but determinedly making her way into the city, for her an alien environment; the grandfather revolutionary, hobbling along on a cane aided by a grandson who reports on activity from in front of the prison; reunions among relatives and the girlfriend of one dissident wondering if he's fooling around clubbing with some other woman.

The Angolan War of Independence was still raging on in 1972, forcing the mostly French crew to shoot in Congo, but with exiled revolutionaries populating the non-professional cast. The use of non-actors mostly works but even with the language barrier it's clear some are downright terrible, barely able to get their lines out.

The classic Argentinian film Prisoneros de la tierra ("Prisoners of the Earth," 1939) is set at a yerba maté plantation deep in the jungle, where an indentured laborer named Esteban Podeley (Ángel Magaña) falls in love with Andrea (Elisa Galvé), the saintly daughter of the camp's alcoholic doctor, Else (Raúl de Lange). The doctor is a hopeless drunk, hired by foreman Köhner (Francisco Petrone) only because he wanted him to bring Andrea along, as he's in love with her also.

At the time it was made, Argentina boasted a thriving film industry, domestic audiences clamoring to hear their favorite local stars in talking pictures. As such the film is impressively slick; early scenes at a saloon strongly resemble American B-Westerns from the mid-1930s, and the at times impressionist cinematography is visually interesting throughout. Early scenes are reminiscent of Werner Herzog's masterpiece Fitzcarraldo (1982): a perilous steamboat journey upriver deep into the claustrophobic, unforgiving South American jungle, led by a German who likes to listen to classical music on a Victrola he's brought along. The exploitation of the workers, meanwhile, is somewhat similar to the first third of John Huston's The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), early scenes with Humphrey Bogart and Tim Holt working for unrepentantly crooked Barton MacLane building oil rigs in Mexico.

Descriptions of the film play up the workers vs. foreman angle, climaxing with a violent rebellion, but unexpectedly the main focuses of the narrative are its conventional love triangle (Podeley-Andrea-Köhner), which plays very Hollywood; and the preponderance of footage devoted to Dr. Else, a character in the final stages of alcoholism and clearly long past saving even when first introduced. Raúl de Lange delivers an almost clinical performance as he descends into violent madness and medical malpractice, but it deviates sharply from where the story seemed to be heading. Where this all leads may be inevitable, but the film is engrossing and artfully made.

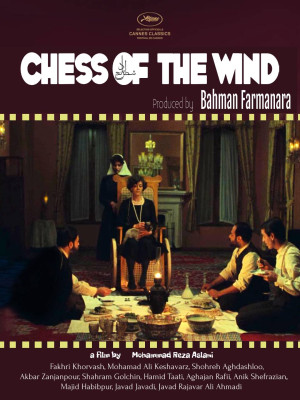

Iranian director Mohammad Reza Aslani's Chess of the Wind (1976) was barely shown at all when it was new and very nearly a lost film. It premiered at the Tehran Film Festival but never exhibited anywhere else and then disappeared into the black hole of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Incredibly, the original camera negatives were discovered by the director's children at a junk shop in 2014 and the film restored in 2020.

Heavily influenced by the cinema of Max Ophüls, the Baroque paintings of Georges de la Tour, and the cinematography of Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon (1975), Aslani's film is set a hundred or so years in Iran's past, where at a stately mansion following the death of its matriarch, various parties fight over control of the rich estate: the ailing, wheelchair-bound adult daughter, Lady Aghdas (Fakhri Khorvash); the supposedly pious yet tyrannical and vulgar Haji (Mohamad Ali Keshavarz), Aghdas's stepfather; Ramazan (Akbar Zanjanpour) and Shaban (Sharam Golchin), Haji's scheming adopted nephews; and Aghdas's devoted handmaiden, Kanizak (Shohreh Aghdashiou).

Like Barry Lyndon, interiors are all lit entirely by candlelight, or at least appear that way, in long and lingering shots of great beauty. The camera is also impressively fluid at other times, particularly as this film, not quite murder-mystery, noir, or Gothic horror but with elements of all three, builds to its frenzied climax.

The kind of film that was possible to make in 1976 if with considerable controversy and unthinkable in the Iran of 2022 is, for its sheer daring alone makes for fascinating viewing, combining as it does parallels to changing attitudes toward Islam and the role of women in the lead up to the Revolution. I don't pretend to have understood it all; there are, for instance, frequent cutaways to fountain where maids and other servants wash clothes and act as a kind of Greek chorus. They're loquacious (the English subtitles struggle to keep up) but I'm not entirely clear of the intent of those scenes. The methodical pacing may bother some, though visually it's so sumptuous and the character relationships so interesting I was never bored.

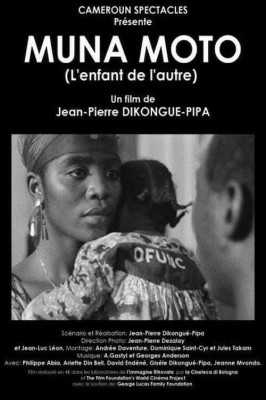

Director Jean-Pierre Dikongué Pipa's Cameroonian Muna Moto ("The Child of Another," 1975) revolves around how traditional cultural values, especially when practiced by those shackled by poverty, can have tragic consequences. Poor fisherman Ngando (David Endene) is in love with Ndomé (Arlette Din Bell) but hasn't the money to pay her father the traditional dowry, a laundry list of items including rice, whisky, chickens and the like amounting to several thousand dollars. Ngando assumes his comparatively wealthy uncle (Abia Moukoko), now his step-father married to his mother and three other women, will give him the money, but he's sexually attracted to Ndomé himself, wants her to bear his child as his four other wives are "barren" (though maybe he's the problem) and plots to steal her away from Ngando. Naively, Ngando thinks if he simply works harder, he can earn enough money to pay for the dowry himself, a determination Ndomé admires, especially watching him singlehandedly chop down enormous trees to sell for firewood.

But, of course, by all appearances Ngando would have backbreaking work for years and years before ever coming up with enough money; in one scene he marvels at his savings, a few crumpled bills and some coins, and one can't help but feel sorry for him.

The narrative unfolds in a series of flashbacks, opening with a climactic moment, then mostly telling the story sequentially but with other flashbacks and flash-forwards. The story, of course, is universal and unavoidably tragic, perhaps so much so I found myself distracted by peripheral aspects. Ngando's and Ndomé's families all live in dirt-floor huts and wear traditional clothing, but when characters travel into the city other Cameroonians are dressed in modern shirts, slacks, and dresses. One presumes these are mostly working-class people, better off financially than Ngando and even the uncle, but maybe instead these are folks who've simply abandoned traditional ways. On one hand, the two families at the center of the story aren't far removed, one presumes, from Cameroonians centuries ago, except that modern world waste products seem to be everywhere: old rubber tires and the like, much of it repurposed as furniture and other items in their huts. Most of the dialogue is in French (from the French Cameroon colonization days) but a lot of it is in unsubtitled Duala and Basaa. We see traditional daily life, yet Georges Anderson's musical score incorporates very ‘70s electric guitar riffs.

From 1943 to 1960 director Andre DeToth made films in Hollywood, including such classics as Ramrod (1947), the famous 3-D film House of Wax (1953) and the great film noir Crime Wave (1954). He began his directing career with six features in his native Hungary, all in the late 1930s just as the war in Europe was getting underway. The colorfully eccentric DeToth -- I met him a few times, when he was still claiming to have been born in 1900, thirteen years older than he really was -- dismissed all his early work, but Two Girls on the Street (Két lány az utcán, 1939) is a crackling melodrama, as slickly produced as any Hollywood movie from the same period, full of energy, but with a Pre-Code Hollywood sensibility, built around two determined, empowered women. (Come to think of it, it's a little like the great Pre-Code film 3 on a Match.)

The first woman is Gyöngyi (Mária Tasnádi Fekete), the daughter of a wealthy family caught up in scandal when her lover leaves her both pregnant and for another woman he plans to marry. Gyöngyi has an abortion, graphically depicted by 1930s standards, including a glimpse of the large aborted fetus, then she goes to work at a Budapest nightclub, playing jazz violin in an all-girl band. (As an actress, Fekete is quite good, but as a virtuoso on the violin she's ludicrously unreal.)

Vica (Bella Bordy), a meek, uneducated, unsophisticated peasant from the same village also makes it to Budapest, finding work as a bricklayer. But even before she can find a place to live she's sexually assaulted by the building's architect, Csiszár István (Andor Ajtay). Vica and Gyöngyi meet on the street, the latter offering to help Vica, eventually becoming a mother-figure to the unformed young woman. (Vica seems to have been written as a character of perhaps 16 or 17, but actress Bordy was 30 years old, two years older than Fekete.)

When Gyöngyi's family hears of their daughter's backstage life, to avoid further scandal they pay her off with a generous monthly allowance, which allows the young women to move into a new apartment -- built by Csiszár István, who also lives there. He falls for Vica without realizing she's the former peasant girl he assaulted, and though she recognizes him instantly, she can't help but find him glamorously attractive, in spite of everything.

A brisk 79 minutes, Two Girls on the Street is nothing DeToth should have been embarrassed about. It's fast-paced melodrama but adult, with two strong women at their center. There's a wonderful scene where a genial alcoholic match-seller teaches her about astronomy, and her sense of wonder about the universe and desire to better herself in all ways possible is charming and captivating. DeToth's obvious drive to experiment and display diverse cinematic storytelling techniques results in a genuine kinetic film bursting with energy while the script he co-wrote has its share of surprises, subverting genre conventions.

The biggest of these subversions, though maybe such characters were not uncommon in Hungary, is the characterization of Csiszár, a cad both sensitive and predatory, one of those types who believes everyone has his or her price, even women in love. The film's curious ending, which I won't divulge here, pushes these thwarted expectations of DeToth's perhaps a bit too far but, overall, I found this the most enjoyably satisfying film of the set.

Each of the first five features in the set shares themes and sensibilities with at least one of the other four, but the sixth, the Indian-made Kalpana (1948), feels rather shoehorned in. While culturally, historically significant, for those not especially passionate about traditional Indian dance forms it's a bit of a slog, despite its aggressive, always inventive visual style.

The only film of writer-director Uday Shankar, one of India's greatest dancer-choreographers, Kalpana is a two-hour-forty-minute semiautobiographical film with Shankar himself starring as Udayan, who from early childhood is passionate about dance, and who struggles to achieve his dream of a dance academy encompassing all of India's myriad regional dance arts. Widely varied dance sequences take the form of Udayan's dreams, his visits to various parts of India, and performances he stages. Shankar's dancer-wife, Amala, co-stars as Uma, a beautiful, Indian Ava Gardner type.

Like Chess of the Wind, Kalpana was met with hostile reviews and mixed audience response (though Satyajit Ray was a fan), then disappeared from circulation for many decades due to a copyright dispute, only to be rediscovered and reassessed after re-premiering in 2008. Some have described it as a "proto-Bollywood" musical, which is true enough, but it struck me more as a kind of Indian Tales of Hoffman (1951), the Michael Powell-Emeric Pressburger film, which along with The Red Shoes (1948) and Oh...Rosalinda!! (1955) fused their aggressively cinematic inventiveness with classical performing arts (dance, operetta, etc.). Like the Powell-Pressburger films, Shankar uses every cinematographic tool at his disposal to enhance the dance sequences, as well as, like his British counterparts, trickery derived from the legitimate stage.

The main character Udayan, apparently like Shankar, is single-minded in his obsession, passionate in his goals, letting nothing stand in his way which, in turn, makes the character come off as insensitive, autocratic, self-absorbed, and ultimately not very appealing. The performances are stylized and broadly theatrical, with Shankar, to western world audiences anyway, coming off as a moody Sabu, full of agreeable energy but also petulant in equal measure.

The movie hints that Shankar may have been much like the character he plays here. Kalpana itself opens with text from the director essentially warning the audience to pay attention and keep their traps shut (you know who you are, Shankar adds). Perhaps understandably, being made when it was, the film is unapologetically nationalistic and openly anti-British, anti-American, anti-Europe; visiting one Indian city Udayan complains "All the filth of Europe and America is here!" and in another scene, visiting rich potential backers of his academy, Shankar depicts them as grotesques, their Indian purity absurdly contaminated by foreign influences.

But the dance sequences and Shankar's use of camera effects is impressive throughout, and the movie's significance, belated in some respects, is undeniable, though I'd recommend watching over two nights, as I did.

Video & Audio

Remarkably, except for Kalpana, the transfers/restorations of the films in this set look great. All are presented in their original 1.37:1 standard aspect ratio with the exception of Chess in the Wind, presented in 1.85:1 widescreen. Scanned from their original 35mm negatives are Sambizanga, Chess in the Wind, Muna moto (all in 4K), and Two Girls on the Road (in 2K). Both first- and third-generation 35mm prints were sourced for Prisoneros de la tierra (scanned in 4K), and Kalpana was scanned in 2K using a 35mm dupe negative and a 35mm print. The uncompressed mono audio, all supported by good English subtitles, is sourced from everything from original 35mm soundtrack elements to theatrical prints, but all are excellent save Kalpana, owing to its less than ideal available elements. There are two films apiece on each of the three Blu-ray discs, and six DVD discs, one per film. All are region "A" encoded.

Extra Features

Helpful supplements abound for each title, and there's a fat (72-page) booklet with extensive film credits, essays, and restoration details. Scorsese himself introduces most of the films (I think he's absent on the last two, which also have different opening credits about their restorations for some reason). Included are many rewarding featurettes, typically featuring new interviews with film historians specializing the various regions, new or archival footage with the directors and/or their children. More than most Blu-ray titles, these are invaluable in contextualizing the works.

Parting Thoughts

Though not quite profoundly dazzled, I nevertheless found Martin Scorsese's World Cinema Project No. 4 very worthwhile and often fascinating, with five of the six films engrossing on their own terms, despite their many unfamiliar cultural and historical aspects, and all six are very good films very much worth preserving and seeing. A DVD Talk Collectors Series title.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian currently restoring a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||