|

|

|

|

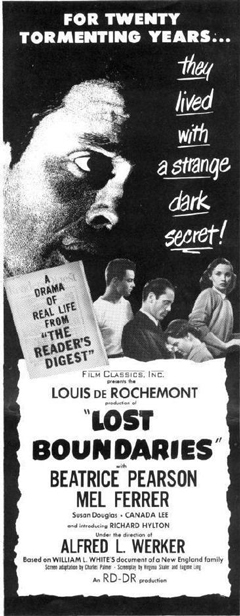

The post-war period inaugurated a trend of "socially progressive" movies, at least until the social consciousness was scalded out of Hollywood by the HUAC hearings and the Red-baiting Blacklist. The most impressive studio movie to deal with race issues was probably Intruder in the Dust, but special mention must be given to an also-ran produced with noble intentions and which succeeded in almost every aspect -- Lost Boundaries. Noted producer Louis De Rochement came originally from the March of Time newsreels and had prospered at 20th-Fox with "true life" dramas filmed where they occurred, like 1945's wartime espionage picture The House on 92nd Street. 1949's Lost Boundaries saw release by Film Classics, a tiny outfit better known for weak foreign imports and Z-grade domestic productions. The slipshod title sequence doesn't match the look of the rest of the picture, which leads this reviewer to theorize that the film was originally finished for a major studio, only to be dumped due to the Red Scare. Lost Boundaries is an uncommonly thoughtful look at racism in America -- a true story of blacks "passing" for white. Reviewers and casual viewers critical of the movie often get the story details wrong. In the 1920s, medical student Scott Mason Carter (Mel Ferrer) graduates in Chicago, marries his sweetheart Marcia (Beatrice Pearson of Force of Evil) and happily relocates to a waiting internship position in the South. Scott is very light-skinned. When his prospective employer (a black doctor) sees Scott he withdraws the job, citing a new rule that only Southern doctors be hired. Scott knows it's because he isn't black enough. Rather than take a job as a Pullman Porter, as at least one of his fellow graduates has been forced to do, Scott holds out for an internship elsewhere. An offer eventually comes from a New England hospital. Scott does well in the job, and lucks out when an opportunity comes his way to assume the practice of a revered doctor in an upright New Hampshire community.

Scott and Marcia settle into the conservative little hamlet, consciously passing for white. Shelley's parents, also light enough to "pass", are concerned about what will happen when their first child is born. Baby Howard is light as well, and so is their baby daughter Shelley. Scott proves himself a worthy M.D., and the locals reward him with their trust and respect -- he's filled the shoes of his white predecessor. Years later Shelley (Susan Douglas of Five) is a teenager and Howard (Richard Hylton) a college student. Both are popular. Musically inclined Howard brings a black college friend home for the weekend, and Shelley, like her peers, refers to the friendly visitor as a "coon". Scott and Marcia realize they've done wrong by not telling their children the truth. It's the middle of WW2 and the call goes out for doctors for the Navy; Scott is offered a commission as a Lieutenant Commander. Howard happily joins up as well. The bubble bursts just as the community is giving Scott a big send-off: a Navy Intelligence man visits to tell Scott that he's been rejected for service. Blacks are not given Navy officer's commissions. The word begins to circulate, invisibly. Shelley goes into a depression, not knowing how to respond to friends that ask her to deny the "awful rumors". Howard experiences an identity crisis, flips out and runs away to New York's Harlem district, where he tangles with the law. He's told the way of the world for Blacks Who Can Pass by a friendly NYPD sergeant (Canada Lee). Scott and Marcia, having enjoyed the acceptance of their neighbors for twenty years, dread what will happen when the whole town determines that they're dishonest pretenders. All of this is handled without sensationalism; the drama is compelling and the small-town atmosphere believable. We like and respect the Carters, and marvel at their optimism and determination. Lost Boundaries benefits from an impressive location shoot and sensitive work from the undistinguished director Alfred Werker. The original location sound recording adds to the air of realism. Lightening the mood are several lively performances, especially Beatrice Pearson and Susan Douglas. A couple of bright musical interludes at the piano are there to lend commercial entertainment value: the talented Carleton Carpenter, soon to become an MGM musical star, plays a boy interested in Shelley. Carpenter sings a cute song, and is deeply confused when Shelley confirms the rumors. The story doesn't get into the reaction of the parents of the friends -- and sweethearts -- of the Carter kids, although we can fill in that gap for ourselves. My initial reaction during the first few minutes of Lost Boundaries was probably typical of a white viewer with limited experience in racial matters: Scott, Marcia, her parents, and Shelley seemed to be obvious Anglos that would never fool anybody. The truth is that the racial divide is really a gradient. Actor Mel Ferrer's facial structure could indicate a black heritage, but the truth is we don't see such things until we're told to look. I initially judged the character by his cultured speech and behavior. Ferrer's previous role was a small part in John Ford's The Fugitive, as a Mexican priest. Actress Beatrice Pearson looks the "least" black, it would seem. The actors playing her parents have a very interesting appearance. The key criticism is of course, that real light-skinned blacks should be playing the roles; hiring whitebread stars seem hypocritical. The answer is simple practicality: in 1949 just fielding the subject matter was extremely risky. Producer De Rochemont couldn't make a movie that would be restricted to theaters in black neighborhoods. Lost Boundaries "passes" for responsible and sensitive reportage. It's far more courageous than the phoney, feel-good issue films made in today's much more open society: what risks does the "our family adopted a football star" movie The Blind Side take? Lost Boundaries shows us that America was profoundly unjust at a time when the political right considered any criticism of society as Red propaganda and Anti-American -- and had the power to demonize artists and end their careers. Movies much less pointed than Lost Boundaries were frequently sidetracked away from wide distribution. Some were picketed and harassed off screens. Most of the South refused to show Lost Boundaries on principle. In his book Blacks in American Films & Television: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, author Donald Bogle ridicules Lost Boundaries, saying that the doctor would never have been rejected by a black hospital, and that the ending note of reconciliation for the Carters is a typical cop-out. 1 According to what I've read, those parts of the film closely follow the experience of the real Doctor Albert Johnston, upon whom the movie is based. Even after the truth came out, the doctor's town continued to accept him. A New Hampshire college even held an anniversary reunion for the film in 1989. 2 One possible point of contention is that the movie makes being black seem like such a terrible thing, even blacks don't want to be black. I don't believe that this criticism sticks. The Carters just want what we all want. As for deceiving people and maybe breaking an unwritten rule or two, what parent isn't willing to stretch the truth if it means a better school or more opportunities for his child? Scott Carter's extended black family understands well that passing is a legitimate response to life for a Negro in America -- if one has the courage to get away with it.

I haven't read the original book so I don't know how much of the truth was fudged in the screen adaptation. In the absence of the facts I'd guess that the Johnston children must have been aware of their true heritage before dad was forced out in the open. One important turn of events was definitely softened. The movie makes Dr. Carter into an accidental recipient of the coveted small-town practice, as a reward for saving the life of another doctor. It's just too good to pass up, even with the associated risks. But we're told that the real doctor Johnston actively pursued the opportunity when it became available, that his plan to "pass" was premeditated. The movie leads us to wonder how the Carters made such a fundamental deception function for twenty years. We initially worry about what will happen if one of the babies is dark-skinned. Dr. Carter goes to the city every week to do research with another black doctor, and apparently nobody becomes curious. The Carters clearly couldn't invite their relatives to visit, which would seemingly strain those family ties. If they kept in contact by phone, the local telephone operator might catch something. Don't the kids ask about grandparents or cousins? I suppose that American blacks working with this issue were careful to protect each other's privacy. What if Dr. Carter had a delinquent dark-skinned nephew, who barged into town to borrow money from his well-off uncle? That's maybe a silly example, but keeping such a basic secret can't be easy. Those questions arise only because Lost Boundaries is very much about reality, and makes so many powerful statements. We're fully on the side of the Carters' deception, as only a racist would deny them the right to pursue a good life in the face of such overwhelming injustice and inequality. An eye-opening early dinner table scene shows various African-American relatives discussing the issue of "passing": just to subsist requires a conspiracy against the status quo. The local farmers and businessmen give Carter a rough welcome, only to eventually accept him warmly. We're impressed by their decency -- when racial issues aren't at stake, that is. What did Carter do when he overheard the locals tell "darkie" jokes in the general store? How did he feel, knowing that the friendship he enjoyed could evaporate at any moment? A town bigot would consider Scott and Marcia to be sleeper agents of racial pollution, waiting for the day when their children can despoil the local bloodlines. Two incidents cut deeply into our preconceptions. The Navy Intelligence man dispenses his bad news as if the good doctor were a felon or a traitor. As Hollywood (and society at large) at this time never even hinted at the appalling racism that existed in the armed forces, this scene really hits hard. Even more to the point is a Red Cross blood drive episode where a nurse objects to mixing "negro" blood with "good" blood. In no way will the nurse compromise her "principles". When Dr. Carter repeats his instructions she allows the glass receptacle to fall to the floor. The scene is an object lesson: self-righteous ignorance cannot be actively opposed without breaking heads. Sidney Poitier never ran up against this kind of wall. 3 The obscure Lost Boundaries is a noble social document damned by the times in which it was made. America insists on its freedoms but controversial films were effectively suppressed without being officially banned. Without resorting to liberal clichés, religious detours or Stanley Kramer chest-beating, Louis De Rochemont's production remains highly relevant. That's not an empty phrase when one regards the compromises, confusion and self-congratulation to be found in some other late-40s race issue movies. 4 Mel Ferrer became a well-known name star but his acting was never as good as it is here. Beatrice Pearson walked away from the movies after this picture and the excellent Force of Evil, a classic film noir that uses the numbers racket as a metaphor for capitalism. The talented Susan Douglas has enjoyed a rewarding career without becoming a big name. The politically active Canada Lee is one of the most famous blacklist victims, dying of a heart attack only four years later. He's remembered for three classics -- all with social messages: Alfred Hitchcock's Lifeboat, Body and Soul and Cry the Beloved Country.

The Warner Archive Collection DVD-R of Lost Boundaries is a fine transfer of this fascinating, entertaining drama. It's an excellent picture for discussing race in school (if schools are still allowed to teach social ethics). I'm certainly intrigued: I wonder if there is any merit to my theory that the movie was abandoned by a large studio. No trailer is included. This was actually one of the first Warner Archives releases from last March, and I'm surprised that I didn't catch it until now.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Lost Boundaries rates:

Footnotes:

1. An excerpt from Donald Bogle's book can be read at Turner Classic Movies' entry for Lost Boundaries. 2. (spoiler:) The conclusion that "the doctor and his family were accepted" might be in question. The final scene shows the Carters still welcome in church, but the visuals are definitely troubling. On the way to church they're snubbed by a neighbor, and they definitely feel uneasy during the services. Visibly shaken, Shelley leaves halfway through and is not seen again. In 1954 Jet Magazine carried this news account of Dr. Johnston being sued for malpractice. Is the suit evidence of local persecution? Obituaries for Dr. Johnson's wife imply that they separated, and that she lived the rest of her life in Hawaii. Did local pressure ruin their marriage? Issue movies encourage us to think that everything that happens in a person's life is related to their "main theme".

Here's a link to an account of the 1989 Keene State College Fortieth Anniversary Lost Boundaries Reunion. Scroll halfway down the page to "Larry Benaquist".

3. Whenever Poitier's characters faced implacable racists, his scripts made sure that he triumphed: if not immediately, then in the end.

4. Two more links: a local New Hampshire article on the film and Louis De Rochemont. See also this Separate Cinema page for a good discussion of black-themed film history.

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with reader input and graphics. Also, don't forget the 2010 Savant Wish List. T'was Ever Thus.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||