Part Two: The Ultimate

Savant Essay:

Cinematic Dreamscape

Savant continues his two-part examination of William Cameron Menzies' Sci-fi classic.

Don't forget to read Part one of this article.

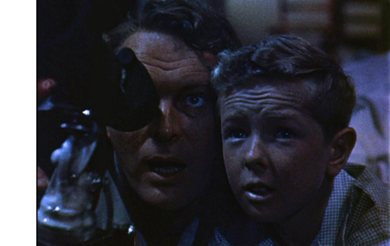

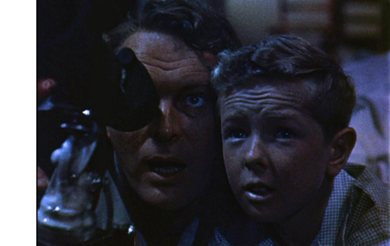

The talented child actor Jimmy Hunt carries the show in Invaders from Mars. A full five years earlier Jimmy appeared in Andre de Toth's Pitfall, a moody film noir. Jimmy plays the six or seven year-old son of disenchanted husband Dick Powell, who is nearing middle age and can't understand why his loving wife and good job don't satisfy him. The most telling scene in Pitfall happens when little Jimmy wakes from a nightmare. Something was threatening him at his

window. Jimmy's mother (Jane Wyatt, later of Father Knows Best) can't understand what could disturb a boy in such a perfect suburban situation. Dad picks up a stack of -- what else -- 'trashy' comics:

window. Jimmy's mother (Jane Wyatt, later of Father Knows Best) can't understand what could disturb a boy in such a perfect suburban situation. Dad picks up a stack of -- what else -- 'trashy' comics:

"Now it's comic books. Where does he get this stuff?"

It's only 1948 and already scapegoats are being sought for the lack of values and direction in American life. Some un-nameable fear is disturbing both little Jimmy and his father... there is something different about the times themselves, an uneasiness, and no one seems able to identify the cause.

In Invaders from Mars David MacLean has a BIG nightmare, and once again his parents blame it on 'those trashy comic books he's been reading.' 1 Think of Invaders as a post-modern version of The Wizard of Oz. In Dorothy's circa-1900 world of dull rural sameness, a dream is a chance to escape into a magical realm. Her adventure explains in strange but logical ways how the real world works. Authority figures are without substance, and one's peace is at the whim of

representatives of Good and Bad engaged in struggles that ordinary people can hardly relate to. If she is brave and virtuous, an innocent can find her way and perhaps discover a few truths about herself in the process.

representatives of Good and Bad engaged in struggles that ordinary people can hardly relate to. If she is brave and virtuous, an innocent can find her way and perhaps discover a few truths about herself in the process.

Dorothy's Kansas world may have been dull, but it had one quality David MacLean's sorely lacks: a sense of security. David's frantic dream is a symptom of the pressures of his daily life, not an escape from it. It's not a magical place Over the Rainbow that one can enter like a Tex Avery cartoon character ('Technicolor Begins Here'). David's dream is an alternate reality so close to his real world he doesn't even know he's left it. Like Dorothy's Oz, David's dream is populated by people he knows, but now they are sinister doppelgängers of their 'real' selves.

Most of the criticism of Invaders from Mars stems from director William Cameron Menzies' decision not to identify David MacLean's adventure as a nightmare visualized literally from David's own point of view. With certain exceptions like 1946's Dead of Night, adults tend to reject outright tales that turn out to 'all be a dream.' One might have to explain to a four-year-old that Dorothy really didn't go to a place called Oz, but adults aren't going to be fooled. David MacLean's nightmare is a cheat that isn't revealed until the end, after 75 minutes of ludicrous illogical characters and plot. Illogical to an adult mindset, that is.

Invaders from Mars has a reputation for scaring the hell out of children because it's that rare film engineered around primal adolescent fears. The nightmare is not only shown from little David's point of view, it is also restricted to his frame of reference and his experiences. In Pitfall, Dick Powell's disenchantment is having an unnoticed psychological effect on his son, who perhaps worries that his father doesn't love him. In Invaders, if the pressures of 1953 are making adults paranoid, what effect are they having on the children?

We know that the 'real' David MacLean is a precocious astronomy buff that lives with his loving parents. His father might not talk much about what he does for a living. Back then we all assumed our dads were doing important work. David might have a neighbor friend named Kathy Wilson (Janine Perreau) whose father might work at the same place David's father works. 9 That's about all we are told regarding David's 'reality.' Everything in his nightmare is a distortion of his waking world, and not to be trusted. There are no reassuring 'winks' to the audience, no loveable Scarecrow who resembles a farmhand back home. David wishes he had an astronomer for a friend, so his dream gives him one, a best pal, in fact. David seems to have a good idea of the woman he wants in his life as well -- sexy Pat Blake (Helena Carter).

Older reference books dismiss Invaders from Mars a fantasy for juveniles, not realizing how completely it expresses juvenile anxieties. We've all been taught that fantasy stories present us with crazy-mirror visions of our everyday world, and we relate to fantasy because of its relevance to 'real life.' 2 David MacLean is insecure, therefore his dream parents 'aren't really his parents.' 'Those trashy comic books' have populated his daydreams with flying saucers and sinister aliens. Authority figures are remote and disinclined to believe him. Beyond those observations, most reviewers can't fathom anything else in the film, let alone the weird continuity anomalies detailed in part one of this article.

The brilliance of Invaders from Mars is that all the 'weirdness' does make sophisticated visual and thematic sense. It isn't convincing to an adult sensibility because a ten year-old, David himself, is 'writing the script' and 'painting the scenery.' Invaders paints a surreal landscape of dialogue non-sequiturs, plot illogic, and crazy character behavior. To an impressionable child of 1953, comic book flying saucers and aliens have a credibility equal to headlines about atom bombs, brainwashing and foreign conspiracies.

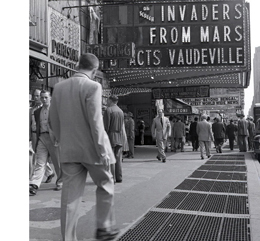

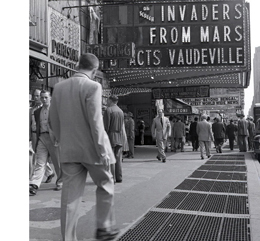

Invaders from Mars' weird fantasy is practically a psychological study of the new postwar American kid, bombarded on all sides by world filled with new technological terrors. The film played to audiences insufficiently hip to realize that a 'silly kid's film' could possibly be worthy of serious consideration. Taken literally, Invaders is incoherent. Taken like, say, Lewis Carroll's Alice through the Looking Glass, it's a mother lode of engrossing ideas.

Breaking Down the Pulp.

Titles: The martial marching music behind the main titles blends with an eerie suspense theme as planets and moons drift by... in 1953, outer space is Big Science, and Big Science is Military Science. The music's real theme heralds a Brave New Future of aggression, expanding into "the vast heavens."

Norman Rockwell Opening: In a few brief scenes Menzies and writer Richard Blake sketch a happy family in their modest home just as succinctly as would the famous Saturday Evening Post illustrator. David and his father's 3 a.m. telescope fun is as wholesome as a fishing trip. The only odd notes are the weird green-bluish colors, and Menzies' precise use of gigantic choker close-ups. Mary and George MacLean are nurturing and sweet-hearted even when awakened in the middle of the night. They're parents too perfect to be true.

Saucer Landing: Our first darkened view makes The Hill look like a flat storybook illustration. When the Saucer lands at 4:41 a.m., David doesn't shrink in fear, he wonders out loud: "Gee whiz!" He's the first of the Cinefantastique sense-of-wonder boys, Spielberg's inspiration for Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Dream-Logic Visuals. At sunrise we see Menzies' minimalist art direction at its most uncanny. The sets are simple one- or two-wall rooms. The view out David's back door shows just a tree and an almost empty horizon. Shots alternate between wide, flattish domestic masters and intense choker close-ups, usually accompanied by blasts of strange music. There is no action montage per se; only tableaux and obsessive details. The huge shoulder of a policeman looms above little David, who strains to see something on the back of his neck. Director-designer Menzies is noted for shots in which the main subject is squeezed into a corner of the frame, threatened by the visual composition itself.

Discontinuity of Angles. In the earlier part of the story The Hill is always seen from a single wide angle view. It's a dream image, the kind of oneiric repeated image that never changes. When George or Mary leave their porch and step into The Hill set, they seem to be entering a different world. The action on the hill stays limited to several obsessive angles: a close-up of a character in danger, a funnel of sinking sand forming in the Pit, and back to the ultra-wide unchanging Hill, as if It were alive and responsible.

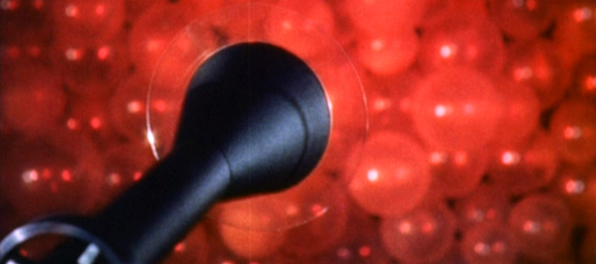

Bizarre Music: Credited composer Raoul Kraushaar, or whoever really wrote the jolting, schizophrenic score to Invaders, invests The Hill and its grasping Sand Pit with a living dimension, an eerie, stomach-twisting vocal effect that seems to be an inversion of a stock 'heavenly chorus.' This incredibly creepy collection of slippery tones will grab the attention of any child. It sounds like a nightmare. It's far more disturbing than a Theremin, if only because of that instrument's overuse. 3 We assume that the chorus is part of the musical score until the scene in which Sgt. Rinaldi crawls up to the Sand Pit. David blurts out, "That noise!" acknowledging that he hears it too. Do the Martians sing as they suck victims into their sand trap, or is David hearing the soundtrack of his own dream? Later, both David and Pat hear the 'Martian chorus' just before they are captured. And the entire cast reacts similarly to a choral burst as the saucer prepares to lift off. The logic of David's dream fully enlists the soundtrack in its surrealism.

'Overplayed' Villainy. Because David is orchestrating the Dream Logic, his parents behave like simplistic baddies from the comic books he reads: If this were a realistic photoplay, his father's sullen demeanor and explosive anger would have Mary MacLean in a panic and running to the neighbors for help. George MacLean's sinister, menacing invitation to show his wife something in the Sand Pit plays like a come-on line for Bluto in a Popeye cartoon. And after Mary too is possessed, they huddle to exchange crazed stage-whisper conspiratorial asides, like a humor-challenged Boris and Natasha. They're so obvious that even Forrest Gump would be dialing the F.B.I..

When 'Quisling' Mary hugs her son at the Police Station, she raises an eyebrow and addresses the camera directly, as if saying, "Yes, I'm possessed." Pokerfaced Police Chief Barrows (Bert Freed) similarly confronts the camera, conveying a chilly alien attitude:"'Yeah, I'm one of 'em too. Got a problem with that?" Menzies makes the Chief's weirdness all the more apparent by shooting his signature close-up in reverse. 4

The faces of these zombified humans all mirror the emotionless-but-intense facial expression of the as-yet unseen Martian Intelligence controlling them.

A Kafka Collection of Characters: One thing David MacLean fully understands is his own lack of credibility and power as a child. Protected, sheltered and ignorant of anything beyond their Davy Crockett coonskin caps, most 1950s kids weren't the streetwise, DARE to Say No, economy-driving consumers we know today. Nobody takes David seriously, not Mrs. Wilson, nor the gas-station attendant Jim, who instantly betrays his confidence. 5 Even benevolent Police Desk Sergeant Finley (Walter Sande) isn't going to understand David's predicament.

Most movie kids David's age have family situations so stable that trouble at home seems impossible. They're still playing with Tinkertoys and Lincoln Logs and wondering which sugary breakfast cereal is their favorite. David instead finds himself in a psychological Hell where his pleas fall on deaf ears, a dark corner darker than that of the most luckless film noir protagonist: your parents have become unfeeling monsters, part of a vast conspiracy to conquer the Earth. Only you know the awful truth, but nobody will even listen to you. You're just a kid.

A Sex Life for David MacLean: In his hilarious article about teen films of the 'fifties, 10 Richard Staehling wrote that before James Dean and Rock 'n' Roll, teenagers really didn't exist as a cultural concept. Invaders from Mars shows what a 10 year-old of 1953 really has on his mind. David probably isn't getting any peeks at the first issue of Playboy but he knows how to tell Virginia Mayo from Aunt Virginia. David's Mom comes right from the glamour girl mold herself. Insecure boys (and men) find beautiful women intimidating, I'm told. For initial viewers of Invaders Hillary Brooke may already have carried a mild taint of villainy, as she played Gale Storm's troublemaking co-worker on the television show My Little Margie.)

David's playmate Kathy Wilson is seen only in her 'zombie' state, with the same staring, unfocused eyes as the MacLeans and Chief Barrows. The knowing, sneaky, creepy look of triumph in Kathy's giant close-ups has a hint of the boyhood sexual distrust of girls that society still doesn't know how to acknowledge. Little girls back then were smarter and better behaved than little boys of the same age. Adults tended to trust and believe them more than us unpredictable boys. Some had actually been given facts about sex, a subject that was 'none of our business.' When hanky-panky occurred, it quite often was girl-initiated. 1950s culture tightly coded proper little girl behavior, making Kathy's 'knowing' smile seem sexually precocious, dangerous. Next stop, Patty McCormick in The Bad Seed.

But the big burner in David's dreamland love life is the incredibly sexy health nurse Dr. Pat Blake. She wears two-tone high heels and (we eagerly imagine) an intoxicating perfume. A crimson handkerchief sticks fashionably, daringly out of her designer nurse's uniform. Pat is as tender as David's mother, yet takes him seriously, accepting him as an adult in all matters. Pat Blake doesn't leave David's side from the moment she finds him. She's a gal one can trust. Forget stuffy astronomer Kelston. It's David and Pat all the way.

When she's manhandled by the Martian slaves, Pat's oh-so perfect uniform is torn at the shoulder just so. Just the way every heroine in action movies from Joanne Dru (Red River) to Virginia Mayo to Maureen O'Hara seem to have their dresses torn at the shoulder. Those foolish censors probably thought an exposed bra strap would be too sexy, but the effect is the exact opposite: if Pat doesn't dress like Mom, what is (or isn't!) she wearing underneath? Invaders from Mars isn't repeating this cliché, it's revealing its source as a little boy sex-thing. Naked woman aren't a part of David's psyche yet... but he's getting there.

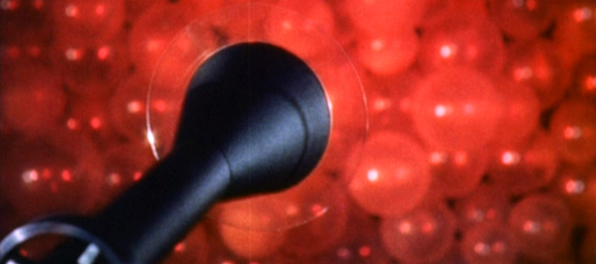

The killer close-up of Pat shows her resting peacefully on the Martian's glass operating table with that one shoulder bared -- and a diamond-like needle pulsing slowly toward the back of her neck. This penetration image is charged with concepts of sex and rape, innocence and violation. Perhaps the 'real' David MacLean has a crush on his school nurse, who is sweet to him. Adolescent guilt, confusion and angst arrive when a boy realizes that the older women to whom he's attracted are going to be 'gotten' by males other than himself. The threat of the Martians taking David's girl away overrides even his anxiety about his parents' fate.

That Wacky Dr. Kelston. Anyone doubting that the text of Invaders comes directly from the mind of adolescent David MacLean needs to reappraise the absurd, pipe-smoking nutcase that is kindly Dr. Stuart Kelston, Phd. (Arthur Franz). We've already witnessed the bizarre dialog when George tells Mary all about his secret work at the Coral Bluffs plant. When she asks what it is, her husband chuckles and replies, "Honey, you know I can't talk about that." 6 But with Dr. Kelston the logic of expository dialogue breaks down completely.

Junior scientist David has a screwy idea of what real scientists do. His imagined best friend Dr. Kelston works in an observatory, smokes a pipe, and comes up with the darnedest, most ridiculous theories out of thin air, just to lay a foundation of explanations for the Martians that will soon be making their first appearance. It is all story exposition that Kelston has no way of knowing is relevant to the problem at hand. If he were being tape-recorded, any investigator would conclude that Kelston must be in league with the aliens. Kelston lays out a rapid series of illogical, baseless non-sequiturs: that the Martians are visiting the Earth in Motherships, that they live underground on Mars and have bred a race of synthetic humans called Mutants as their slaves! David chimes in with cheery support, as if they've discussed these theories before. Poor Pat's first polite objection to this baloney is met with the arrogant "I'm a scientist" retort made hilarious years later in Ghostbusters.

Apparently, a scientist's work is to invent absurd theories out of thin air, and then persist in believing them until they're disproven. Pat has the gall to follow up with more mild questions, which are dismissed with patronizing allusions to public skepticism of the airplane. If George MacLean has a loose concept of national security, Kelston is a madman. He spills the beans to David and Pat about the entire secret Coral Bluffs rocket project, which, naturally, is military in nature. 7 The science / military collusion seems complete when Dr. Kelston phones his Coral Bluffs Army contact Colonel Fielding (Morris Ankrum) to recommend an immediate security alert. There's no hint of ideological conflict between scientist and soldier here, not even the token sympathy given Dr. Carrington of The Thing from Another World. David's adolescent view is clearly right-wing... no peaceniks on this bus.

"A real General wouldn't say that." The soldiers show up, led by the Gung-Ho Colonel Fielding, who behaves as if his life has been spent waiting at full readiness for a cue to start fighting Martians. Perpetually worried and stressed, Fielding is the right man for the job -- he initiates a massive troop and materiel movement just on Dr. Kelston's say-so. Colonel Fielding's phone calls set in motion the barrage of stock footage padding detailed in part one of this article. More evidence of the David dream-logic of events: Fielding and company personally call on the family of poor dead Kathy Wilson, and then climb atop David's roof to observe the Sand Pit. As in a dream, the view of the Pit from the roof is exactly the same as when one is standing on the ground below. Everybody climbs on the roof. That they look so ridiculous perched up there among the gables can only be because the visual is David's dream notion of what being on the roof is like -- when he's never been up there!

U.S. Troops: Ultimate Heroes. When postwar films are written up it's not often acknowledged that a great many of the young adult men on view are fresh out of uniform. Most of these non-career civilian soldiers had an entirely different attitude to war and fighting than today's glamorized gladiators. Veteran James Whitmore in Them! is the prime example of the sane & humane ideal of the American warrior, circa 1954: decency personified, there to protect and serve. This idea is infused in genres where it's not expected. The horde of police that raids the oil refinery at the end of White Heat evokes a vision of criminals at war with an America that is an army. David MacLean shares this reverence for military might and authority. The soldiers in his dream are perfectly disciplined, whether following ridiculous orders or totally ignoring the presence of dishy dame Pat Blake.

The army engineers are just as scientifically clairvoyant as civilian Dr. Kelston. Captain Roth (Milburn Stone) somehow knows all about infrared Ray Guns that can melt tunnels in the earth, and immediately diagnoses the control device retrieved from the late Kathy Wilson's skull. A couple of minutes later, he's got it rewired as a divining rod to locate the Martian tunnels. Roth has perhaps Invaders' best, most insane dialogue line: "Don't worry son. They aren't going to use a complicated device like this just to kill people."

Captain Roth gives David a reassuring pat on the head; a detail that contrasts with the bit in The Day the Earth Stood Still when a soldier gives a similar pat to a kid that tells him that fugitive spaceman Klaatu went thataway in a taxicab. Audiences boo and hiss the little Judas in Day, a film with an exceptionally non-military attitude. Most '50s Sci-fi idolizes the armed forces the same way David and Col. Fielding appreciate brave Sgt. Rinaldi, who charges single-handedly up The Hill like John Wayne in The Sands of Iwo Jima.

Dream tension. The furious action that concludes Invaders from Mars becomes even more dreamlike with the repetitions of shots and scenes outlined in part one. Dialogue lines are also repeated. Young David's, "Colonel Fielding!, Colonel Fielding!" is heard so often it becomes an unending echo. As Part One took pains to point out, these repetition patterns make the ending more dreamlike in two ways.

First, a high level of anxiety is maintained while the actual story progression slows to a crawl. A classic anxiety dream situation is 'running in place but not getting anywhere,' exactly the feeling that all those repeated shots impart to Invaders. Second, the repetition forces us to fixate on the images that keep re-playing, a fixation that has the obsessive quality of dream logic. In our dreams, shocking moments seem to hang forever in the consciousness, or illogically 'come back again, but for the first time,' over and over.

In the dyslexic dream logic of Invaders effect can precede cause, and explanation can precede observation. The 'surprises' found in the underground Martian nest are not surprises at all, having been perfectly described earlier by Dr. Kelston and Captain Roth. "Mutants!," shouts David upon first seeing the huge green Martian slaves. 8 Zombie Sgt. Rinaldi's verbal intro for the Martian Intelligence is completely redundant. David pummels the fishbowl as if having always known that the tentacled sphinx inside is fully in charge. The most illogical, dreamlike event in the tunnels is David's ability to recognize and operate the clarinet-like Infrared tunneling Ray Gun. Nobody, including David, has seen the Gun's full function, yet David takes charge and leaps into action, an instant expert in alien technology. David MacLean's dream may be a mirror for his anxieties, but there's plenty of room within to cast himself as the know-it-all hero.

David MacLean's dream-confusion between wish fulfillment and dread becomes complete as the climax draws near. The ending montage has several dynamic up-tempo changes. The music kicks into high gear when the tanks fire to begin the assault on the underground tunnels. At the height of the tension, when David is running in place during the escape and retreat, time-progression suddenly comes to a standstill. The rising arc of tension breaks, with a music change (a harp arpeggio) and the addition of the superimposed bits of visuals from before. As the music score becomes more ethereal, the dream seems to be folding in upon itself, laying itself to rest, even with David still running, still unreleased from his nightmare. The eerie reverse-action scenes that conclude the montage become mirage memories fading into themselves, those striking dream images that disappear when one tries try to remember them.

Were this a normal dream, in the morning David would have a burst of memory, a sudden consciousness of an entire dream storyline populated with details and events. But it would be fleeting, because only some dreams fully resolve in the light of day... most evaporate in the act of being recalled, leaving behind only a random image or two laden with mysterious significance. Every so often the strongest of these rises to surface into normal consciousness. They may bring back a memory of the dream, or just remain mysteries. Invaders from Mars captures the quality of a half-remembered dream. The outlines are unforgettable, but the details are weird absurdities.

William Cameron Menzies' direction and images make Invaders the most expressive nightmare film in the science fiction genre. The topography of its dreamscape is as vivid as the art film dreams of Fellini and Bergman. The nightmare sums up the shared anxieties and subconscious wishes underlying the sheltered, secure '50s childhoods of David MacLean and millions of American boys like him. It's as if it were pulled from the minds of males born between, say, 1942 and 1956. Does the dream world of Invaders from Mars 'speak' to younger audiences? Does its surreal logic still appeal, still seem valid? Or is it hopelessly dated, an artifact for the appreciation of Sci-fi fans and graphic artists? Savant would like to know.

Footnotes:

1. Remember, folks, whenever you hear pundits blaming dire social problems on the arts and artists, start looking for little radio implants in the backs of their necks.

Return

2. During a screening of Woldgang Peterson's The NeverEnding Story, Savant remembers hearing 'Ahhs' of audience approval when that film's terrifying 'Nothing' is explained: what seemed a shallow fairy tale suddenly became meaningfully multi-dimensional.

Return

3. Another uncanny use of weird choral music that succeeds in creating a subliminally disturbing atmosphere is Krystopher Komeda's score for The Fearless Vampire Killers. Runner up: Roger Wagner's choral effects, the only music in Robert Montgomery's The Gallant Hours, make us feel that the entire story of Admiral Halsey is happening in a weird memory museum of recent history.

Return

4. Shooting Chief Barrows' close-up in reverse was probably a practical aid. The actor could start on his mark, perfectly framed and in focus, before stepping back away from the camera. But it still comes off as bizarrely pre-Lynchian.

Return

5. The gas station attendant Jim is uncredited actor Todd Karns, who also played George Bailey's younger brother, war hero Harry in It's a Wonderful Life. Wonderful was a flop in 1946 and probably no influence on Karns' role in Invaders.

Return

6. If this wasn't a private joke in Invaders it certainly became one in 1980's Airplane!, in the 'Raid on Macho Grande' flashback sequence. Chalk up Sci-fi fan Airplane! producer Jon Davison for that one, Savant bets.

Return

7. Dr. Kelston arrogantly states that once nuclear weapons can be 'anchored' in space, any country that "dares attack us can be wiped off the face of the Earth in a matter of minutes." Swell. Funny that in America's very first serious Sci-fi film Destination Moon, the deal-maker that clinches funding for the private moon rocket is the stern warning that if America doesn't use the moon as a nuclear weapons base, its enemies will.

With only a few exceptions, Sci-fi films from Forbidden Planet to 2001 have the same militaristic themes. Acknowledging this is Wim Wenders' Until the End of the World with its Indian Nuclear Satellite threatening the Earth at the dawn of the millennium. The American press parroted the official U.S. line that our Space Program was non-military, while the American Sci-fi film told the truth, years before it came to pass. Are these Martians really conquering Earth or, like the Arachnids of Starship Troopers, just trying to neutralize a nuclear threat?

Return

8. The green velour mutants always remind Savant of the Winkie Guards from The Wizard of Oz. It's something about their plastic noses, and their slavish stupidity.

Return

9. Janine Perreau was a popular child performer in the early 1950s. Savant met her in 1996 when her actress sister Gigi Perreau was directing a play at my daughter's school. Janine remembers Mr. Menzies being nice. She was told to pick flowers and drop through a trap door on the hill, where a stagehand caught her! She's proud of her 'zombie' close-ups, and was happy to be told that she played probably the first 'possessed' child on the American screen, years before The Innocents, Village of the Damned or The Exorcist.

Return

10. Staehling, Richard, From Rock Around the Clock to The Trip: The Truth about Teen Movies, in Kings of the Bs: Working Within the Hollywood System: An Anthology of Film History and Criticism, A. Dutton 1975 NYC, Edited by Todd McCarthy and Charles Flynn

Return

11. Added Link: a 1999 letter response by John Mastrocco.

12. Special Thanks to Larry Tuczynski for help with this article.

Don't forget to read

Part One

of this essay-article.

Also, Savant's Review of the

2002 Wade Williams DVD release.

Text © Copyright 1999, 2015 Glenn Erickson

DVD Savant Text © Copyright 1999, 2015 Glenn Erickson

|

window. Jimmy's mother (Jane Wyatt, later of Father Knows Best) can't understand what could disturb a boy in such a perfect suburban situation. Dad picks up a stack of -- what else -- 'trashy' comics:

window. Jimmy's mother (Jane Wyatt, later of Father Knows Best) can't understand what could disturb a boy in such a perfect suburban situation. Dad picks up a stack of -- what else -- 'trashy' comics:

representatives of Good and Bad engaged in struggles that ordinary people can hardly relate to. If she is brave and virtuous, an innocent can find her way and perhaps discover a few truths about herself in the process.

representatives of Good and Bad engaged in struggles that ordinary people can hardly relate to. If she is brave and virtuous, an innocent can find her way and perhaps discover a few truths about herself in the process.