Part One: The Ultimate

Savant Essay

A two-part examination of a Sci-fi classic that, at least in Savant's opinion, should be showing in the Louvre.

Finally! As of 12.09.02, a decent DVD is available for Invaders from Mars.

Read

Savant's review.

The modest 1953 science fiction film Invaders from Mars has been a fascination since childhood. I don't think anyone has written about it in a way that really captures its genius; of all '50s Sci-fi I think it is the most visually sophisticated, perhaps the most cinematic and a work worthy of the term 'great art.' If you hate writers that jam sub-Freudian meanings into movies, have no fear. My arguments are based on the movie we all can see, and don't try to conform the film to fit some graduate-student agenda. On the other hand, this article probably is more for confirmed Sci-fi aficionados than the general DVD Savant reader. I thank both for their patience.

But if you want to hear some discussion about Invaders from Mars, this is the place. Invaders is so rich in ideas that I would not claim to have a handle on the whole subject. Part 2 of this article is the actual essay and argument for the film as an overlooked masterpiece. Part One presents a lot of relevant but loosely organized background, production, and restoration information. It also discusses some editorial structures within the film that are needed as setup for the essay.

PART ONE: Background.

William Cameron Menzies

Invaders from Mars was made relatively early in the '50s Sci-fi cycle when the field was still dominated by "A" quality efforts. Optioned by one set of producers, a script by John Tucker Battle eventually landed with Edward L. Alperson, who made the uncharacteristically brilliant decision to put the entire project into the hands of legendary production designer and sometime film director William Cameron Menzies. Menzies was the genius who practically invented the concept of production design, on big silent movies like Douglas Fairbanks'

The Thief of Bagdad. Menzies' unique graphic sense elevated the films of Sam Wood (Our Town, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Kings Row). Menzies made Hollywood history with David O. Selznick by singlehandedly engineering Gone With the Wind's visual dimension. Without

him the divergent contributions of a half-dozen directors might have created a shambles.

The Thief of Bagdad. Menzies' unique graphic sense elevated the films of Sam Wood (Our Town, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Kings Row). Menzies made Hollywood history with David O. Selznick by singlehandedly engineering Gone With the Wind's visual dimension. Without

him the divergent contributions of a half-dozen directors might have created a shambles.

Menzies directed several earlier films, most notably the Science Fiction spectacle Things to Come. Partly due to post-release re-editing, the show gave Menzies the undeserved reputation of a director who couldn't handle actors or block scenes. The Savant article on the versions of Things to Come hopefully helps to explain how the haphazard slashing of that film from 110 to 96 minutes unfairly contributed to the denigration of Menzies' talent. Another fantastic Menzies effort was The Man He Found, a thriller about a journalist who discovers a nest of Nazis in postwar America. After it was completely finished, RKO head Howard Hughes decreed that it be reworked to turn the Nazis into Communists experimenting with biological warfare weapons. The final title is The Whip Hand.

Synopsis (with spoilers)

Invaders tells the story of young David MacLean (Jimmy Hunt), who witnesses the 4 a.m. landing of a flying saucer from his bedroom window. Burrowing into a sand pit, the Martians trap David's kindly father George (Leif Erickson) and plant a radio-activated control device in his neck. Now a zombie-agent, George MacLean spreads the Martians' influence by luring others into the pit: David's mother Mary (Hillary Brooke), army General Mayberry. The Martians are soon in control of the local police as well.

Young David responds to the trauma of finding his parents transformed into inhuman automatons by confiding in his local astronomer friend, Dr. Stuart Kelston (Arthur Franz). With the help of attractive public health nurse Dr. Pat Blake (Helena Carter), they determine that the Martian invaders plan to use their radio-controlled human operatives to sabotage the atomic rocket being developed at Coral Bluffs, a secret government base nearby. Kelston informs the Army, which surrounds the sand pit. David and Pat are captured and taken into the buried Martian saucer, which they discover contains only one real Martian, a disembodied, tentacled head in a glass globe. It is in telepathic command of a crew of giant, bug-eyed, green Mutant slaves. Hard-bitten Army Colonel Fielding (Morris Ankrum) launches a desperate rescue mission into the maze of Martian tunnels; David and Pat are freed before they can be implanted with control devices. The Army sets its demolition charges inside the eerie spaceship but the Mutants seal off the escape tunnels. Young David mans a Martian infrared Ray Gun to burn an exit tunnel to the surface, and the entire cast runs for cover. When the explosives finally detonate, David awakens: the entire adventure is revealed to have been but a dream. But was it? Once again, David is awakened by the sound of an approaching spacecraft...

The Production

Invaders from Mars was filmed in color, which automatically gave it an edge in the 1953 Hollywood independent market. Part of Menzies' job as designer was to choose a color scheme that would look good in a now long-abandoned color process. Original prints of Invaders from Mars have an otherworldly color texture, with slimy greens and blues and vivid reds. 1 Despite persistent urban myths, the movie was not filmed in 3-D, even though Menzies' depth-enhancing design makes it look more three-dimensional than many bona fide 3-D features.

Almost all the movie was filmed on carefully designed sets. One oft-repeated bit of trivia is that the bubbles lining the walls of the Martian tunnels were inflated condoms -- clusters can be seen wobbling as soldiers run by

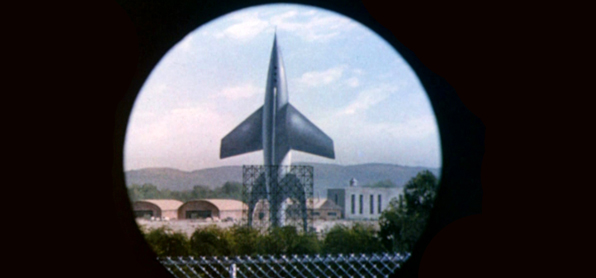

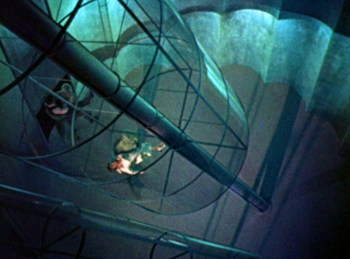

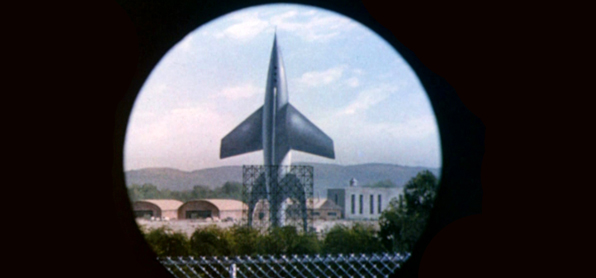

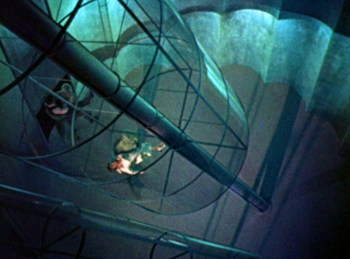

them. Some sets were cleverly recycled. Assassination target Dr. Wilson's lab is the same set as the forbidding Police station, redressed. Special effects man Jack Cosgrove executed a number of effective matte paintings that help stretch

the budget. David's house and telescopic views of the atomic rocket are both mattes. Clever glass paintings augment a number of saucer interiors, such as the dynamic angle down the glass tube above the Martian operating table.

them. Some sets were cleverly recycled. Assassination target Dr. Wilson's lab is the same set as the forbidding Police station, redressed. Special effects man Jack Cosgrove executed a number of effective matte paintings that help stretch

the budget. David's house and telescopic views of the atomic rocket are both mattes. Clever glass paintings augment a number of saucer interiors, such as the dynamic angle down the glass tube above the Martian operating table.

The Infamous Zippered Aliens.

Eager fans sometimes enjoy heckling maladroit Sci-fi, and Invaders from Mars gives the casual monster movie bashers a big target. Most often derided are the plush velour jumpsuits used to represent the Martian slaves. Writers Robert Skotak and Scot Holton report that in the absence of a better budget a friend of the producers jumped on her Singer sewing machine and whipped up the suits practically overnight. This accounts for the legendary famous zippers running up the spines, as they are pretty obvious. But perhaps what we see is clothing and not the mutant's actual skin? Should that be the case, the Earth is being invaded by big lugs wearing comfy pajamas.

The bug-eyed Martian faces were achieved with a simple plastic eye-nose-mouth combo mask worn like sunglasses. In stills, the Martian slaves remind one of the moth-eaten Cat suits the wardrobe man of The Bad and the Beautiful tries to push on producer Kirk Douglas. Not the most convincing Aliens concocted for the screen... point granted.

The Sand Pit Hill Set.

Menzies appears to have invested the majority of his art department's resources in one extravagant set, the hill behind David's house that leads to the treacherous Sand Pit. It is a truly remarkable design for a number of reasons. A slightly curved path winds up the hill between some leafless black tree trunks. The path is paralleled by a broad plank fence, a favorite design motif of Mr. Menzies. Atop the hill, the blackened fence dips out of sight into the largely unseen Sand Pit beyond. We're always trying to see 'more' of the Sand Pit; a pair of trees center screen sometimes blocks our view. 2

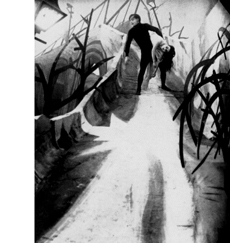

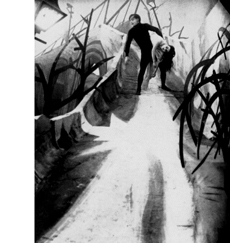

The hill is 'deceptively artificial.' On first impression it seems to echo the design concept of a shot in the 1919 Cabinet of Caligari that depicts a bridge over which Cesare the Somnambulist kidnaps his female victim. (→) The Invaders hill appears to be a similar diorama-like design. Its perspective is flattened out and until the last-act battle it is always presented in locked-off, static angles. It looks just strange enough to resemble a painted backdrop. But when an actor walks up the path, all sense of

perspective goes haywire. When three-dimensional people walk into what looks like a two-dimensional image, they diminish in size. The effect is a subtle contradiction of visual logic. (side-by-side comparison just above ↑)

perspective goes haywire. When three-dimensional people walk into what looks like a two-dimensional image, they diminish in size. The effect is a subtle contradiction of visual logic. (side-by-side comparison just above ↑)

It's a 'reverse forced-perspective' optical illusion: a deep set is purposely made to appear shallow. George and Mary seem to get smaller than they should as they reach the top of the hill, and they take a lot of steps to get there. But the trees at the rear of the set don't give the right 'perspective clues,' so it almost looks as if the couple is shrinking as they walk. The subtle effect is much more apparent on a large screen.

Stock Footage.

Whether by necessity or by design, producer Edward Alperson shamelessly padded his movie with stock footage. To represent the regiments Colonel Fielding has summoned to surround the Sand Pit, large sections of a WW2 training film on how to transport tanks by rail have been spliced in. A small independent outfit like Alperson's could not hope to get the free cooperation of the National Guard, as did the studios that produced The War of the Worlds and The Day the Earth Stood Still. The footage of tanks pulling into position amid the greenery around the Pit is presumably stock footage from earlier productions, some of it displaying rather non-American looking tanks. Evidence of padding is also seen earlier, when David and Doctor Kelston realign the telescope. Long, uninterrupted takes of the Observatory's rotating cupola bring the movie to a dead stop. These are probably not stock footage, but pickup shots filmed in Los Angeles' Griffith Park.

The Strange Repetition of shots.

But the biggest invitation to nitpickers in Invaders from Mars is the constant and obvious repetition of shots. When those aforementioned tanks start shooting, a handful of angles are reused over and over. One specific image of a shell blast is seen at least a dozen times just by itself.

Not just stock footage is repeated. In the Martians' underground lair, many shots of shuffling Martian Mutants and running soldiers appear to have been recycled. There seem to have been at most four actual camera angles in the Martian tunnel set. The same six velour suits shambling past, repeated three times, become eighteen Martian slaves. These angles have also been flopped left-to-right, and the flopped versions repeated too! If you look at the back wall of the tunnel in these shots, the same three-bubble pattern can be seen repeated ad infinitum, often back-to-back. Likewise, when David's parents flee the army in a two-setup, no-budget car chase, both shots are flopped horizontally, and shown again.

During the underground fighting, more two- and three-shot sequences are repeated. Sgt. Rinaldi (Max Wagner) drags David out of the operation room and down to the next level inside the saucer. A few moments later, David breaks free and dashes back upstairs -- and the same exact shots are reused to show Sgt. Rinaldi dragging David out a second time. When a group of soldiers shoots down a Mutant ("Blast him!"), the fallen alien gets back up again, seemingly unharmed. The soldiers doggedly open fire a second time, and the entire sequence of them shooting, and the Mutant toppling, is repeated exactly as shown only seconds before.

Crazy Suspense Editing.

Invaders from Mars uses a 'deadline' tension device to raise the excitement level in the battle. The soldiers find that their escape exit is delayed, and have only a couple of minutes to dig their way out before their own demolition charges go off. A huge close-up of the time-delay readout of the bomb is intercut with fleeing soldiers and the surface of the Sand Pit as the saucer attempts to take off. Editors usually cheat these kinds of sequences a little, stretching the material to last longer than it should, all in the service of suspense. A good comparison is the time-stretched atom bomb countdown at Fort Knox in Goldfinger. Here in Invaders the bomb's second-hand defies all logic, passing the same markers on its dial again and again. Also repeated is the saucer's initial emergence from the Sand Pit. Surely nobody expected anyone over the age of six to accept this sequence at face value. It's of course a subjective effect not unlike a dream, or in any tense situation, when time seems to expand and contract depending on how what is happening effects us.

If a filmmaker shoots twenty minutes of film stock, and makes a ten-minute movie out of it, the movie is said to have a 2 to 1 shooting ratio. The joke to Invaders is that the completed film has so many repeated shots, its shooting ratio is 1 to 2 !

A Bizarre Montage like No Other.

This is the point where this classic alien invasion movie goes Wholly Radical. For some it becomes an editorial tour-de-force, and for others a cinematic joke. The simultaneous actions of ticking bomb, escaping saucer and fleeing troops overlap to a point where time stops progressing altogether. It's as if Einstein or Stephen Hawking zapped the movie camera. The detonator never hits the Zero mark. David never reaches the bottom of the hill; the saucer never breaks free of the Sand Pit. We're stuck in the grammatical Present Progressive.

David runs for his life in an unending close-up as a prolonged optical montage begins. Striking images and violent action from earlier scenes are recapitulated, superimposed over David's running face and intercut with that same repeated shell blast. The music downshifts out of its martial frenzy into a previously unheard ethereal theme, not unlike the final movement of Holst's The Planets. Just as we realize that David's running is locked into a non-progressing limbo, a new series of superimposed images begins, now playing in reverse. The scenes chosen this time are non-violent but eerily disturbing: David leaping from the embrace of his parents; the zombie police chief (Bert Freed) putting on his hat. The odd visions eventually dissolve into a star-scape of planets receding, retreating away. A whole Philip K. Dickian universe is going to sleep.

Concurrent with a clap of thunder, a final explosion 'breaks' the montage and restores David to his bedroom. The 'dream' part of Invaders from Mars is over. For some viewers the experience is a meaningless joke. In a series screening at UCLA long ago, this scene elicited an enthusiastic response even as it remained a mystery. I haven't yet read anything about Invaders that satisfactorily addresses the meaning behind Menzies and editor Arthur Roberts' crazy quilt editing of these last reels. This is my interpretation.

A Victim of Version - Manipulation.

The American cut of Invaders from Mars is about 78 minutes long. A few months after it was completed, Arthur Franz, Helena Carter and young Jimmy Hunt were rehired to film new footage to enable the film to clear foreign censors. England apparently nixed the dream story structure outright, for reasons that are unclear. It's the same structure used in The Wizard of Oz, after all. The new footage negates all that was unique about Menzies' original conclusion. Inexpressive angles were filmed of the three actors reaching the bottom of the hill and ducking behind an Army vehicle. The effects animation of the saucer landing was reversed to make it look as if it were taking off, with an added flash to show it being destroyed by the Army bomb. One of the prop trees lamely tips over. Pat glibly announces that, now that the control source destroyed, David's parents are safe. Then there is a dissolve to David sleeping, and a tight angle on Drs. Kelston and Blake standing at his bedroom doorway cooing, 'He'll be safe now." End of show.

Collector (and now record producer) Bruce Kimmel once possessed an uncut 35mm print of just this reshot sequence. He allowed Savant to transfer it to tape in 1988, and resynchronize its audio -- a defect that probably enabled the print to survive to become part of Kimmel's collection. Four years later it was used as an extra on the Special Edition Laserdisc of Invaders from Mars from Image. As can be expected, they did not fix the audio flaw.

The original English ending reportedly skips the weird montage finale altogether. Pasting this cop-out ending onto the film meant losing a couple of minutes of running time. To make up for it, and whatever else the Brit censors might have cut out, a second new scene was filmed with the same three actors. In the observatory, just when the trio is discussing the likelihood of living beings on Mars, the new footage kicks in. Jimmy Hunt's neck grows at least an inch and his haircut changes. Dr. Kelston takes his two visitors to a new corner of the Observatory to view a conveniently displayed photo album with news clippings of flying saucer sightings. He then opens a cabinet and produces big models of three 'typical' saucer shapes. David is already familiar with these exhibits. After several minutes of pointless discussion, an impressed Pat accompanies the two UFO experts back to the desk, where they resume their seating positions so the film can pick up where it left off.

Until the late '70s this alternate English version was just a rumor in the U.S. But then television prints began to circulate that incorporated some of the reshoot material in odd ways. Savant knows of four versions of Invaders from Mars:

1) The original cut. This is viewable once again on the 2002 DVD. In Los Angeles, the original cut played on television in B&W throughout the 1960s, suddenly appeared in color in about 1971 and disappeared in the mid- '70s.

2) The English cut. It drops the montage finale and adds the observatory scene and the lame no-dream conclusion. The B.B.F.C. clocks this cut at just under 82 minutes. That observatory scene drags on quite a while. It's on the 2002 DVD as well.

3) A television cut Savant first saw in 1979. The same as the original cut, except for a number of annoying alterations, using pieces of the footage shot for England. The heroes now run to safety, and the saucer explodes in the air, but the story still resolves as a dream as in the original. Some dialogue lines have been deleted. Informed that the escape tunnel is hopelessly blocked, Colonel Fielding no longer shouts, "Start digging!" In addition, minor editorial lifts were made all the way through the picture to (reportedly) pick up the pace.

4) A TV version Savant taped in 1989, time-expanded to make the film fit a two hour time slot with commercials. This version has the original ending, but includes the full observatory reshoot scene as well.

There's only one explanation for all this: film collector Wade Williams. Hailing from Kansas City, in the early '70s Williams began announcing that he had rights to a number of Science Fiction films including favorites Rocketship X-M and Kronos. Williams began the dicey practice of altering prints of 'his' films, as Rohauer had once done to the classics of Buster Keaton as a way of re-registering them under new copyrights. For quite a while Williams seemed interested only in the 'improved' versions he re-edited. The original Rocketship X-M had used pretty crummy V-2 rocket stock footage that didn't match models seen elsewhere in the show. Williams hired some Cascade effects alumni (including cameraman Dennis Muren) to shoot replacement footage featuring a proper-looking rocket model. This is the version that appeared on television, VHS and Laserdisc. The original unaltered 1950 Rocketship X-M did not return until Williams put the film on DVD, and we're not sure if it's really fully original.

Wade Williams reissued Invaders from Mars to theaters in the middle '70s, with the changes listed above in versions 3 and 4. The dialogue lines were (reportedly) excised because audiences laughed at them. This puts Williams in the company of earlier film importers that cut scenes out of foreign imports of The Mysterians, Reptilicus, Gorath, and Varan the Unbelievable because screening audiences laughed 'at the wrong places.'

Savant rented several beautiful-looking 16mm prints of this show in the 1970s and once saw a perfect 35mm trailer on a giant screen at Filmex that knocked my eyes out. A 1993 Image laserdisc has a wonderful selection of extras and posters, cut scenes and even a comic book, but its copy of the film is an appalling mishmash cobbled together from a number of wildly divergent sources. The Image producers threw their net far and wide to find decent source material for this 'labor of love' disc. Yet their presentation jumps from patches of excellent quality, to ones with heavy damage, to passages that look like a bad color photocopy. Clearly, they were trying to reconstruct the film from bits and pieces. Wade Williams' name appears nowhere on the laserdisc, which carries the legend, 'Richard I. Rosenfeld presents a film from the Johnar Library.' Was there a question about Wade Williams' copyright claim? Has he the only decent copies of the film? We're told that the film's original negative is AWOL.

As I continue to the second half of The Ultimate Invaders From Mars please believe me when I say that Invaders once looked sensational. I believe that pristine original prints or elements still exist because the clips on a TCM documentary (included on DVDs and Blu-rays of Forbidden Planet) look far better than any full copy yet released on video.

Footnotes:

1. Invaders from Mars release prints were not in standard Cinecolor, a two-color system used for low budget Westerns, by lowercase studios like Allied Artists that wanted to avoid the more expensive (and sometimes big-studio controlled) labs. Cinecolor prints had two emulsions, each adhered to opposing sides of the film base. It was much like the long-abandoned two-strip Technicolor, but employed opposite hues. An excellent example of original Cinecolor can be seen on the Olive Films Blu-ray of Flat Top.

Invaders actually came out in improved Super Cinecolor, a process that more closely approximated a full spectrum. Blues were blue and whites were white instead of shades of cyan and orange. The cameras still shot normal Eastman negative, the point being to circumvent Technicolor patents. See the Cinecolor explanation on the informative Widescreen Museum site. (note: help with this information came from correspondent Paul Samuels.)

Return

2. The plank fences are indeed a favorite motif with William Cameron Menzies throughout his career. They can be seen used throughout Gone With the Wind and Kings Row.

Return

3. Research source: Liner notes from the 1992 Image Laserdisc, itself referenced to an article in Fantascene magazine #4, written by Robert Skotak and Scot Holton.

Those Who Dare - Advance to the

Invaders From Mars Part 2

Essay.

Text © Copyright 1999, 2015 Glenn Erickson

DVD Savant Text © Copyright 1999, 2015 Glenn Erickson

|

them. Some sets were cleverly recycled. Assassination target Dr. Wilson's lab is the same set as the forbidding Police station, redressed. Special effects man Jack Cosgrove executed a number of effective matte paintings that help stretch

the budget. David's house and telescopic views of the atomic rocket are both mattes. Clever glass paintings augment a number of saucer interiors, such as the dynamic angle down the glass tube above the Martian operating table.

them. Some sets were cleverly recycled. Assassination target Dr. Wilson's lab is the same set as the forbidding Police station, redressed. Special effects man Jack Cosgrove executed a number of effective matte paintings that help stretch

the budget. David's house and telescopic views of the atomic rocket are both mattes. Clever glass paintings augment a number of saucer interiors, such as the dynamic angle down the glass tube above the Martian operating table.

perspective goes haywire. When three-dimensional people walk into what looks like a two-dimensional image, they diminish in size. The effect is a subtle contradiction of visual logic. (side-by-side comparison just above ↑)

perspective goes haywire. When three-dimensional people walk into what looks like a two-dimensional image, they diminish in size. The effect is a subtle contradiction of visual logic. (side-by-side comparison just above ↑)