|

|

The Hollywood Children of

Ray Harryhausen

(Written 1999)

Ray Harryhausen is unique in filmdom: a quiet, focused artisan obsessed with stop motion animation who carved a successful career making films in which a special effects artist could be the star. Harryhausen came to the fore back in the 1950's when a mention of the term stop motion elicited blank stares or at best a vague association with George Pal's Puppetoons. Almost the only stop motion pioneer before Ray was the great Willis O'Brien, who made one enduring landmark classic and several notable effects epics but sadly spent most of his career struggling with uncaring studios and shady producers. In the end these 'producers' forced him to put out cut-rate imitations of Harryhausen films (The Black Scorpion, The Giant Behemoth, or used his name to launch their projects but dropped him along the way (The Beast from Hollow Mountain, King Kong vs.

Godzilla).

Only one Harryhausen film, Jason and the Argonauts, is

presently on DVD at this writing, with The Seventh Voyage of

Sinbad eagerly anticipated.

Information on Ray Harryhausen is no longer difficult to find. His name has gone from Famous Monsters of

Filmland cult status to mainstream fame. Richard Schickel made an excellent documentary on him, so

he doesn't exactly have to be introduced to anyone anymore. Mister Harryhausen's legacy is alive

everywhere in Hollywood. He inspired a generation of effects people including a core of stop motion-based

artisans who rambled around Hollywood in the 60's and 70's that I've had some contact with. There are

stories that should be told about these talents.

Savant arrived at UCLA in 1970 with a scholarship to the film school and little else but Alfred Hitchcock and Ray Harryhausen floating around in his head (and a little Peckinpah already, I suppose). Practically the first day at the dorms I connected with another dormie, an incredibly talented artist and fellow Valley of Gwangi addict, Randy Cook (aka Randall William Cook). Randy was serious about stop motion and was already making elaborate gag films and the like; his fame at the UCLA film school would later be assured with the production of his single-8 Project 1, a wicked satire of the (we thought) pompous politically-correct film-school faculty. Whereas the average 1972 student film was either embarrassing poetic mush or angry wannabe agit-prop, Randy had other ideas. He fashioned animation puppets into caricatures of film school professors. One of them was a dead ringer for Louis Clyde Stoumen, a lecturer who had shot Arch Oboler's end-of-the-world scifi film Five and Ida Lupino's Outrage, and who had won Oscars for documentaries. Randy's film was called Attack of the Stew Men and was ten minutes of hilarity about a Dracula-like professor (played by student Robert S. Birchard, now an animation editor and noted film writer) who dispatches a Frankenstein-like goon to kill an innocent film student (Douglas Haise, now a noted ragtime pianist). It seemed the student had produced a film 'with no redeeming social content whatsoever', which meant that "He must be destroyed." The puppet homunculi are slipped into Haise's possession. At night they come to life. Picking their noses and creeping through his apartment, the devil-dolls strangle the poor student with his own roll of Super-8 film. End of saga. The film professors were so dumbfounded at the screening they didn't know how to react.

Randy Cook doing horror makeup for a Savant UCLA film, circa 1972.

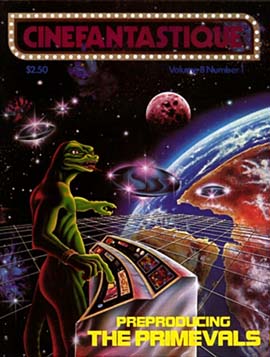

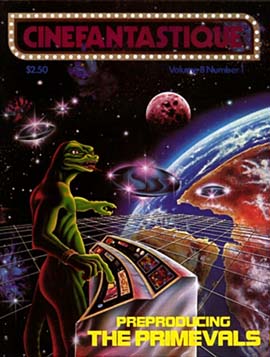

About this time Randy took me along on a visit to the Lake Hollywood house of animator David Allen. David (who, sadly, just recently passed away) was affiliated with Cascade pictures, an effects shop on Seward street that created mostly effects for television commercials. We saw elaborate model castles and animation puppets for a film Allen planned about a fairy tale giant, and a baleful green toadlike dinosaur puppet that squatted under a glass bell. I would later run into David again while researching matte stands for Doug Trumbull's Future General corporation, and had a major visit in 1978 when Allen was preparing bigtime to launch his major project The Primevals. Randy Cook had cowritten the script with David and was pitching in along with most every other pal of Allen's. The shop was strewn with Lizardmen puppets and clay maquettes. Future effects notables Ken Ralston and Dave Carson worked side by side with model makers like David Stipes. The Primevals became the topic for a full issue of Cinefantastique (volume 8, number one), only to be canceled at the last moment; it was eventually filmed by Full Moon in the middle 90's, only to lie unfinished due to money problems.

Cinefantastique, 1978: full coverage for a film that went unmade.

Also active at the time were James Aupperle and Doug Beswick, who I met by accident when they were animating monsters for their Planet of Dinosaurs in 1976; Savant literally ran into one of them carrying a Tyrannosaurus through the hall of a mixing studio called ScottSound where they had rented a tiny room in which to set up their animation apparatus.

Most of the Cascade group also worked at one time or another on Flesh Gordon, an X-rated porno spoof (later edited down to an R) of Flash Gordon films that boasted top-notch effects. Designing and

building models for the show was Greg Jein. Jim Danforth animated a sequence for Flesh Gordon and told the producers he didn't want his name on the film. They responded by spelling it backwards in the credits! Since the maker of Gordon was basically a fly-by-night producer of porn flicks, the paychecks came irregularly. Frequent work stoppages and mini-strikes caused the filming to drag on for a couple of years.

Also involved with this effects community at an early date was Dennis Muren, who now has enough ILM effects Oscars to serve as tenpins in a bowling alley but at the time was an ambitious cameraman/producer. He and David Allen had teamed up to make a semi-professional occult monster movie with a stop motion monster. It had been picked up by schlockmeister Jack H. Harris (of The Blob fame), was expanded into Equinox and got a pretty good release in 1971. The two had already worked on a project called Raiders of the Stone Ring and filmed test footage for it as early as 1969, with helmeted lizardmen attacking helpless cave dwellers. Many changes later, it would eventually become The Primevals.

Jim Danforth was possibly the chief Harryhausen acolyte and had started working on effects for 'real' movies at Effects Unlimited in the late fifties, a full decade before the rest of 'his generation'. Jim's stop motion talents ended up on display in a variety of films. Besides animating the out-of-control firetruck ladder in It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World and certain shots in Master of the World, Danforth was one of the main animators on Edward Small's 1961 Harryhausen ripoff, Jack the Giant Killer. The film used Seventh Voyage's Torin Thatcher, Kerwin Mathews and director Nathan Juran and was so similar even Danforth stated it was a clear imitation. Most viewers of The Outer Limits remember Danforth's creepy animated ant-monsters in The Zanti Misfits episode.

It was Danforth who in 1970 would be nominated for an effects Oscar, for When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth and be the first stop motion artist to be so honored since Willis O'Brien himself. When Dinosaurs was a followup film to One Million Years B.C. with effects by Ray Harryhausen. Ray remained a minor industry figure whose films were ignored by the Academy while big budget epics raked in the effects nominations. Given that it was a non-Hollywood Hammer film, it's always been a mystery to Savant how When Dinosaurs came to be nominated at all.

Fiercely independent, working and struggling for perfection in an industry that used and abused their talents, these animators often had highly emotional reactions to those who were not true believers in their craft. Savant once received a (probably deserved) dressing-down from Allen over the place of computers in special effects. And Jim Danforth returned his nomination to the Academy in protest over the voteless granting of a special effects Oscar to the de Laurentiis King Kong remake of 1976, which he said was an outrage to the effects branch of the Academy. Danforth's gesture was an empty one to all but those of us who knew the commitment of these underdog effects people; Savant tended to agree with Danforth's assertion that de Laurentiis had bought the nomination. (The same way he seemed to have bought the reviews. The Charles Champlin LA Times review lauded the film, especially its Tyrannosaurus

duel. Since there was no such scene in the film, Savant concluded that Champlin had written his review without even paying attention to the film.) Such was Danforth's standing in the industry, that no one accused him of sour grapes; Jim was preparing a Universal remake of Kong when it was derailed by the de Laurentiis production.

Producer Schneer and magic-maker Harryhausen.

Harryhausen had been blessed with something most of his 'children' lacked, a steady relationship with a loyal producer, in Ray's case, Charles H. Schneer. Many have complained

about the lack of production values in Harryhausen's early shows and the lack of good scripts in the later ones, but the fact is that Schneer kept Ray working and turning out movies. Were it otherwise his great talent would have subsided into a hobby or he would have found himself animating Pillsbury Doughboys and the like for television commercials.

Jim Danforth's wonderful dinos for Ruled the Earth were the yardstick for realism until the breakthrough of Jurassic Park in the 90's; he's worked in effects constantly but has done far more matte paintings than stop motion work. Randy Cook and David Allen bounced from one lacklustre project to another in the seventies, contributed effects to films whose production troubles or plain producer cheapness made their effects look like the weak link (The Day Time Ended, Q, The Winged Serpent). Not that these films weren't entertaining or worthy, but so few outlets existed for the craft that even the big names had to take what they could get. For instance, the extremely low-budget independent The Crater Lake Monster enlisted the talent of Allen, Cook, and newcomer Phil Tippett, who built the stop motion model. David Allen eventually got his Oscar nomination for Young Sherlock Holmes. Randy Cook's contribution to John Carpenter's The Thing was largely cut out ('My credit lasted longer than my shots!' Randy would always say) but can be seen in workprint form on the deluxe DVD of that title. His socko Devil Dogs in Ghostbusters did stay on the screen, happily. Randy capably directed the effects and did the animation for The Gate and its sequel. Often an actor (I, Madman) and a director (The unreleased, quite good Demon in the Bottle), Randy's now finally snagged a dream assignment designing elves and hobbits for a new three-part Lord of the Rings movie being produced in New Zealand.

The watershed film for these effects people was Star Wars, of course, which gave stop motion a boost along with the computer-driven camera effects pioneered by John Dykstra, Richard Edlund and Dennis Muren. As part of the original ILM effects bash in the San Fernando Valley, Star Wars employed several of the 'old bunch' to make monster masks to augment the cantina scene, and gave Jon Berg and Phil Tippett a big push with the hologram-chess scene. After that the old school of stop motion took a back seat to ILM's showy advances. The overwhelmingly dominant name in the field is now Phil Tippett, whose work on titles like RoboCop got him the Jurassic Park assignment. Digital dinosaurs eventually replaced Tippett's stop motion creations. After initial concern over being rendered obsolete, Tippett ended up supervising Jurassic's CGI work. His melding of both CGI and stop motion culminated in the phenomenal arachnids of Starship Troopers, in a way that left much of the stop motion generation of the '70's far behind.

Yet even in unfunny comedies like Caveman, the fun and genius of simple stop motion comes through. Just watching David Allen cleverly animate Ringo Star riding a silly-looking

dinosaur, flesh & blood Ringo from the waist up and a model from the waist down, makes one applaud what

ingenuity achieves when faced with limited resources. Tippett and Muren's Go-motion, where computer

activated mechanics move the animation model during exposure to create a natural motion blur on film, was

a high tech way of overcoming the 'strobing jerkiness' often associated with stop motion. It was first used

on the Taun-Taun in The Empire Strikes Back and even more effectively for the villainous dragon

Verminthrax Pejorative in Dragonslayer. Danforth, Allen, Cook and company had previously achieved the same effect through low-tech means. In The Day Time Ended they placed a sheet of glass between the camera and the model and blurred parts of the image with vaseline judiciously smeared on the glass!

Some of the appeal of special effects is directly tied to its artifice, its fakery. Suspension of disbelief is more than simply being fooled by what's being shown; it's a willingness to enter a fantasy world. That quality is earned by the special effects artist the same way a magician earns our belief in his stage magic. For special effects fans, the kind for whom a quiet and media-invisible man like Ray Harryhausen is a star, the joy of watching an effects film, and particularly a stop motion animation film, is seeing the expression of the artist come through. Willis O'Brien's love of boxing is evident in the Tyrannosaurus duel in the original King Kong. Ray Harryhausen's humanoid creatures often move with a pantomime that is part cartoon and part Acting 101. Joe Young (a gorilla), the Cyclops of The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad (a mythological monster) and the Ymir of 20 Million Miles to Earth (a Venusian alien) all exhibit the Harryhausen signature, an elbows-up, gyrating, weight-shifting dynamism, each major move preceded by a counter-gesture. A forward lunge is always preceded by a backwards rocking motion. Double-take reactions of surprise are frequent and accompanied by broad, melodramatic arm gestures. Harryhausen seems to have evolved this on Mighty Joe Young, adding his own intuition to O'Brien's teachings. Joe's actions are stylistically quite an advance beyond those of ol' Kong. Harryhausen infused dramatic qualities into his non-humaniod creations too. He made The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, an 'emotionless' lizard, into the emotional focus of the film, sort of a big, pissed-off puppy that is uniquely endearing. By the time of Gwangi, his last prehistoric epic, Harryhausen seemed capable of animating dinos in his sleep. Always fascinating to watch, Gwangi has that uniquely Harryhausen illusion of weight and mass. He's always a breathing, shifting ton of dino-flesh instead of a pound of painted foam rubber, far more 'alive' than the actors of the piece.

Audiences applauded these moments in a way that 90's theater crowds hardly ever do anymore. Jim Danforth

elicits belief in the reality of his Mother and Baby dinosaur in When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth; they

play like a doe and her fawn and it is disappointing that their screen time is so brief. Randy Cook's

theatrical personality comes through in his creations as well. The animation of Caveman's stoned

Tyrannosaurus flailing its tiny arms about in a stupor expresses perfectly Cook's infectious sense of

humor. In the middle of that dumb comedy, Savant laughed out loud like he was back at UCLA watching Attack

of the Stew Men again.

I've included copious links to IMDB files for these artists and their films . . . a quick way to see just

how many of them contributed to some of the biggest fantasy pix of the 80's and 90's.

In the 1970's, Emmy Award-winning effects man Ernest Farino published a pioneering fanzine dedicated to stop motion and Harryhausen in particular called FXRH. Savant had only one copy of one issue until he (sigh) loaned it to the wrong person.

Text (c) Copyright 1999 Glenn Erickson

DVD Savant Text © Copyright 1997-2001 Glenn Erickson

Go BACK to the Savant Index of Articles.

Return to Top of Page

|

|