| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

Cloverfield |

|

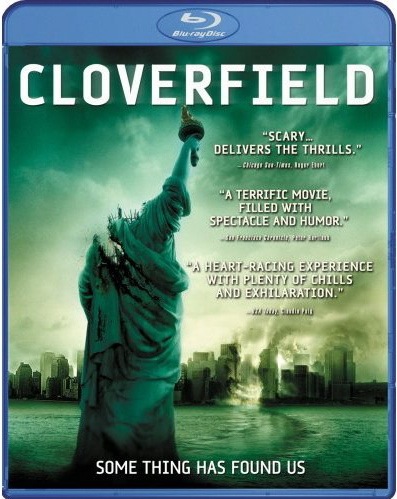

Cloverfield Paramount 2008 / Color / Blu-ray widescreen / 84 min. / Street Date June 3, 2008 / 39.99 Starring Michael Stahl-David, Odette Yustman, T.J. Miller, Jessica Lucas, Lizzy Caplan, Mike Vogel Cinematography Michael Bonvillain Production Design Martin Whist Art Direction Doug J. Meerdink Film Editor Kevin Stitt Written by Drew Goddard Produced by J.J. Abrams, Bryan Burk Directed by Matt Reeves |

adapted from an earlier Savant Review

Cloverfield on Blu-ray? Irresistible. Savant couldn't wait to find out if the show, much of which was reportedly filmed on video equipment with less resolution than a Blu-ray disc, would really be improved in the new format.

Technical advances in filmmaking have traditionally been utilized to make movies cheaper, not better. Improved film stocks gave us movies made without lights, and today's digital production pre- to post- enables us to make movies without having to flesh out a reality before the camera. Now comes a movie that's a hybrid of techniques, a blockbuster effects show filmed largely with low-cost video cameras. Even its promotion was remarkable, using stealth clues and a 'viral' marketing campaign that began with a cryptic teaser that hit movie screens last July.

Cloverfield is an old-fashioned monster movie where the monster itself is an unexplained mystery. Instead of spending time on scientific theories and pseudo-scientific rationalizations, the show simply puts the viewer in the subjective position of a small group of young adults who suddenly find themselves in the middle of a terrifying disaster. Nobody stops to philosophize, sing songs or remember Mom, as they're all running for their lives with nary a chance to catch their breath. It's a hollowed-out monster movie: there's no time to formulate an explanation for the giant beast seen only in disturbing glimpses.

Viewers and critics immediately tackled the question of the monster's meaning, providing a curiosity factor missing from other attempts to revive 50s-style monsters. Because the disaster happens in New York City with both imagery and context that evokes the TV coverage of the 9/11/01 attacks, Cloverfield clearly taps that trauma, if only on the visceral level.

The filmmakers wisely shy away from referencing 9/11 directly. Although the film's advertising art shows a ravaged NYC skyline, the director's official stance is that Cloverfield was made with the idea that America should have its own 'national identity' monster like Japan and its Godzilla. That notion doesn't really stand up, as America knows very well that it already has the best monster-myth ever, and his name is King Kong. If the colossal 'thing' in Cloverfield represents anything, it's a generic unreasoning fear, the feeling that chaos and bloody disaster could come from anywhere at any time. If that's what 9/11 means to people, okay, but Cloverfield really doesn't connect with anything political. The horrible terror crime that was 9/11 is not an existential mystery, it's a political-criminal reality. The Cloverfield monster is just an unexplained 'thing'. 1

Unexplained Things, however, can make for great entertainment. Cloverfield may not be as meaningful as some claim, and its clever style 'gimmick' may not please film purists, but it delivers the first-person video game 'reality' vibe that the audience wants.

When The Blair Witch Project came out in 1999 everyone said that it was a one-off, a gimmick film that couldn't be repeated. I remember being told that a well known direct-to-video producer had commissioned a copycat movie about kids in a haunted house. He put some actors and a couple of video cameras in an old house and simply waited for things to get scary. That brainless scheme repeats the game plan of the makers of Magical Mystery Tour, who thought that a wonderful Beatle Happening would spontaneously erupt if one just took four Beatles and added a camera. Lesson: 'Reality' fare is no less contrived, engineered and scripted as traditional entertainment.

Cloverfield repeats the basic Blair Witch gag with a judicious application of digital effects. The film isn't cheap, but its budget is miniscule compared to its nearest competitor in scope, Roland Emmerich's 1998 Godzilla remake. Given his head to discover new horizons of profit, TV's Lost producer J.J. Abrams has basically pulled the same brilliant gag done by Alfred Hitchcock, 50 years ago. Big budget filmmaker Hitch 'poached' on the low budget domain of William Castle, saved money with a TV crew approach and came up with a superior, grossly overachieving horror flick: Psycho. A goodly portion of Abrams' Cloverfield is produced only a few notches above direct-to-video fare, yet it hit screens with the impact of a high-powered, expensive blockbuster. As the film's 'star' is its unusual format, a non-star cast has been recruited; the top ten or so actors are listed in the credits alphabetically. The filmmakers boast of grabbing entire scenes with a $1500 off-the shelf pro-sumer video camera, without benefit of studio facilities. That's the kind of investment / payback ratio that Hollywood LOVES.

Audience reaction to Cloverfield was immediate and positive. The crowds definitely felt 'in the picture', experiencing the movie's monster thrills right along with the characters in the movie. Reams of arguments have been generated about the film's style, pro and con. It's been over-praised by some and called a gimmick by others, but the fact that the style connects with its intended audience negates most orthodox protests. Like it or not, the format concept has been elaborated to the point of transcending its own gimmickry.

Movies and TV have been playing with handheld and erratic camerawork for a couple of decades now, beginning as a foolish style choice that said a jerky camera somehow made things more 'real'. A feature that really achieved something with this idea is the opening of Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan. Its splintered, jagged jumble of D-Day horrors wasn't cheap, but it put viewers on the defensive. Forced to strain to follow what was going on, the audience had no opportunity to analyze what they were seeing. With no time allowed to discern between reality and effects, the short sequence created a 'heightened reality.'

Cloverfield, somewhat like United 93 and The Bourne Ultimatum, loosens up on Spielberg and editor Michael Kahn's jackhammer rhythm but forces us to watch intently to comprehend the action. Important clues and the elusive Cloverfield monster zip through the frame in subliminal doses, like glimpses seen out of the corner of one's eye. Cloverfield adds another level of distance to the viewing experience by pretending to be 'found video' in the style of The Blair Witch Project. Great pains are taken to suggest that the images were are seeing were discovered on an 'evidentiary' tape recovered in Central Park after the monster attack.

That part has been well documented: the bars & tone opening, the date & time burn-ins and all the other things we expect to see in amateur videos. The majority of the taping is done by Hud, who's been given the camera to document the goings-on at the farewell party. That technically makes Hud the 'auteur' of most of what we see, and people who know how video cameras are used and abused will immediately understand what's going on. Hud continues taping when he has promised not to, and sneaks up on partygoers trying to conduct private conversations. The Cell Phone generation knows very well that nothing is 'real' until it is recorded, and the act of recording is its own justification. Having a camera lens shoved in one's face is a common occurrence. In an early scene a girl finds herself being taped in a compromising situation, and she just laughs it off: "I hope this doesn't show up on YouTube!"

The filmmakers' ingenuity shows when the functions of the video camera approximate the conventions of old-fashioned storytelling. Necessary exposition is dealt with by having the partygoers give videotaped 'testimonies'. Hud doesn't realize it at first, but he's taping over a recording made by party-boy Rob Hawkins four weeks before (April 27). The main horror action of the night of May 22 is periodically interrupted at places where Hud stops the tape, allowing bits of the old recording to peek through. The video bits function as strange, ragged 'flashbacks' to the secret romance between Rob and Beth. One moment Rob is among a terrified crowd in flight from a giant monster, and then he's suddenly smiling and happy with Beth at Coney Island, four weeks earlier.

The filmmakers make the most of the possibilities and limitations of hand-held continuity. Director Reeves explains that when the camera jerks around so violently, making 'invisible' cuts is relatively easy, enabling an unbroken camera view to continue 'without cuts' for what seems minutes at a time. After an initial section where 'Hud' makes mistakes and takes a lot of trash video of the floor, etc., the first-person handheld style becomes more calculated. Hud captures relevant details and dramatic moments with a virtuosity that would be the envy of Frederick Wiseman: Cinema Perfect Coincidence-Vérité. 'Random' camera-pointing just happens upon ideal two-shots. Hud also expresses relationships within a scene, as when Rob and Beth are showcased on either side of the party. Not only is Hud a darn good movie director, he has somehow telepathically intuited the connection between Rob and Beth before it becomes common knowledge. The camera is pointing at or almost at the perfect spot time and time again. By the dawn, the few survivors seem more concerned to give us perfect shots than to save their own lives. Of course, after an hour of playing dodge ball with a jerking camera, the audience welcomes this final clarity, consistent or not.

The only moment I found really laughable is when the camera watches two people struggling and straining to crawl off the roof of a tilted and crumbling skyscraper, into the relative safety of a building still standing upright. After those two people barely save themselves, the cameraman covers the same ground in three or four easy hops, like a mountain goat -- and gets a good video record of it at the same time.

The real point of this scrutiny is to demonstate that Cloverfield is just as artificial as any standard film overloaded with lame cutaways and generic coverage. After 100 years of trying to make the camera invisible, this new style goes in the opposite direction to make camera-awareness the most important part of the cinematic equation. Jean-Luc Godard frequently violated standard rules to prove to the viewer that they were, after all, only watching a movie, but 'normal' audiences either rejected or didn't comprehend his intellectual game. Cloverfield brings advanced Cinema 101 games down to the public playing field. 2

Cloverfield plays like a house afire, augmented by an aggressive, nerve-pounding audio design. After one stops searching for dramatic depth in the uniformly young and attractive characters, it's easy to accept them as terrified protagonists, arguing and crying and opting to stay together for emotional security. The movie confects a good reason for not crossing the Brooklyn Bridge to safety, and for running against the tide to Columbus Circle. They encounter mini-parasite monsters that spread horrible contagion through bites, and run through a darkened subway as rats flee under their feet.

Like any fun monster movie, this one needs to be cut some slack. The instantaneous military response isn't very credible from a logistics point of view, unless the National Guard has a policy of maintaining troops primed & ready to fight Manhattan Monsters at a moment's notice. That's no more a deal-killer than the field hospital that is set up within a couple of hours of the first sighting. Also, the Alien -like exploding body tangent seems hastily shoehorned-in; a few seconds later one of the witnesses is unaccountably making juvenile jokes about things in the dark. Less welcome is finding a major character impaled through the chest by a piece of rebar: the heroes just pull her off (Ooh, that's gotta smart!). A few minutes later she's walking and functional, instead of laid out in shock. Young kids these days do indeed seem to be impervious to harm, but that's a bit much.

I fall down laughing reading some web responses calling Cloverfield a major breakthrough or work of art. It's a fine monster show by smart filmmakers, an old-fashioned genre piece hyped with a gimmick that's both fun and rewarding, within limits. As in Roger Corman's Attack of the Crab Monsters each scene introduces a new thrill, and these days that's saying a lot. Also like an old Corman film, Cloverfield hasn't an ounce of fat. The entire picture is 84 minutes long. Subtract the end credits, and it's only 74 minutes long. That gave theater owners half again as many showings per day!

The packaging for Paramount's Blu-ray of Cloverfield continues the film's 'secret government document' theme, with an anti-theft sticker that doubles as an official seal. The transfer is much clearer than the DVD, with many supposed hand-held camcorder passages that look like quality Hi-Def work. In an interview, the filmmakers talked about having to degrade some images that simply looked too good -- we wonder if they were allowed to look better for the Blu-ray disc. We appreciate the format's ability to re-run scenes: Who just got killed on the Brooklyn Bridge? We can turn on the English subtitles to catch details missed on the big screen.

Director Matt Reeves' motor-mouth commentary is almost as relentless as the film's frantic editing style, yet he's both clear and informative. He talks about the picture from all angles. Using relatively cheap videotape, Reeves was able to film rehearsals and rerun every scene to his heart's delight in record time. That doesn't necessarily reflect badly on his directing ability -- choosing the 'good stuff' is still the hardest task. The entire project overflows with youth, energy and technical know-how cleverly put to use.

A full list of extras is below. They amount to a stack of featurettes, deleted scenes and gag odds and ends. The featurettes (all in HD) are slick and entertaining.

Cloverfield was filmed in an atmosphere of secrecy, with the actors not even knowing what kind of movie they were making until after they had signed on. This kind of control is now typical in Hollywood, where 500 computer effects people could easily blab every detail of a show. On Close Encounters only 40 or so people had access to the inside dope on the movie's special effects. What with non-disclosure contracts flying left and right, these days you can't get anyone to talk about the movies they're working on, sometimes even one that's been in the can for three years. Powerful producers have a long reach, and nobody wants to be shut out for tattling.

The effects-related featurettes are quite a revelation. Only a small percentage of the film was actually shot in New York. Bits of backlot main streets were filmed with greenscreen backings and entire backgrounds were added later -- many scenes are almost all CGI. The entire subway system scene was filmed in a large loading dock in San Pedro! The film still must have cost plenty, unless these beautifully integrated backgrounds of New York can be ordered up by the yard. A brief piece on the design of the monster itself yields only a few hints as to its nature, which in the film remains a stubborn mystery. The designer, at least, thinks that the creature is a newly hatched baby on the rampage because it's confused and frustrated. He also explains that he tried to give it sympathetic qualities, something that never occurred to this reviewer!

The deleted scenes are three short snippets of extra party material and interplay between Marlena and Lily. The alternate endings are barely different than the film's satisfying coda back at Coney Island. The outtakes are a series of gag and blooper moments. Unique to the Blu-ray is a "Special Investigation Mode", touted as being an "Enhanced viewing mode with GPS tracker, Creature Radar, Military Intelligence and more!" The disc is preceded by several theatrical trailers, including one for the new Indiana Jones movie.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Cloverfield Blu-ray rates:

Movie: Very Good / Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Featurettes: Commentary with Director Matt Reeves, Document 1.18.08: The Making of Cloverfield; Cloverfield Visual Effects, I Saw It! It's Alive! It's Huge! (creature design); Clover Fun (Outtakes), Deleted Scenes, Alternate Endings.

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: June 11, 2008

Footnotes:

1. Of course, the urgency to hang a label on the monster is a strange phenomenon in itself. It can't just be, it must be something. Which makes us want to stencil giant red lettering across the monster's chest: "I AM NOT A METAPHOR".

Return

2. In childhood, almost any movie can overwhelm our defenses and seem a '1st person experience' -- ah, those were the days. I personally didn't feel that the 'reality' trick in Cloverfield was working for me, but it was obvious that it did work for many in the audience around me. Am I some kind of superior, sophisticated viewer? No way. I'm just as easily 'transported' by a good movie as anyone, and have a habit of not seeing through the mysteries in mystery movies, even some of the easy ones. It's just that in Cloverfield, the clever style focused my attention on how it was being made. Once seen, the monster was impressive, but not all that interesting. The Cloverfield monster has plenty of impact but little or no resonance. He's about as iconic an 'American Godzilla' as the Bat-Rat-Spider Crab from the jolly cinematic turnip The Angry Red Planet.

Return

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Subscribe to DVDTalk's Newsletters

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |