|

|

|

|

Ranald MacDougall was a highly successful screenwriter who helped Joan Crawford make her career comeback at Warner Bros., and later directed her in Queen Bee. In 1958 he served as both writer and director for independent producer-actor Harry Belafonte's MGM project about the end of the world. It's not clear if the movie was prompted by Stanley Kramer's highly publicized On the Beach, but MacDougall's CinemaScope attraction hit movie screens months before Kramer's show. The seriousness of the film's "unusual" theme is reflected in MGM's promotional materials, which stress the eerie spectacle of Harry Belafonte roaming the empty canyons of New York City, apparently the only person left alive in the world. Previously, the few stories dealing with this kind of subject matter had been low budget science fiction thrillers like Target Earth!, and were sold accordingly. The World The Flesh and The Devil comes across as a class attraction. Pennsylvania coal miner Ralph Burton (Harry Belafonte) is inspecting some tunnels when a collapse almost buries him alive. Five days later, realizing that rescue efforts have halted, Ralph digs his way out. He finds no people anywhere, and reads newspaper headlines about a cataclysmic disaster -- an airborne isotope weapon with a half-life of five days has apparently wiped out humanity. Ralph makes his way to New York City, crossing the Hudson by foot because the bridges and tunnels are jammed with abandoned automobiles. Giving up hope of finding anyone, he moves into a swank apartment and rigs up a power source for his lights. Then Sarah Crandall (Inger Stevens) shows up. She's been following Ralph around, afraid to make contact with him. Sarah and Ralph are delighted to find each other, but the relationship doesn't get past the tentative stage because Ralph has no faith in the future of an interracial relationship. He instead sets up a daily radio broadcast to search for other survivors, claiming that he'll find an appropriate man for Sarah. The fellow who does arrive in a small boat is Benson Thacker (Mel Ferrer), a nice-enough white guy who immediately stakes his claim on Sarah. The trio quickly devolves into a lopsided triangle: Ben wants Sarah, Sarah thinks she prefers Ralph, and Ralph refuses to make up his mind. With the world on reboot, should the existing racial "rules" be kept or abandoned?

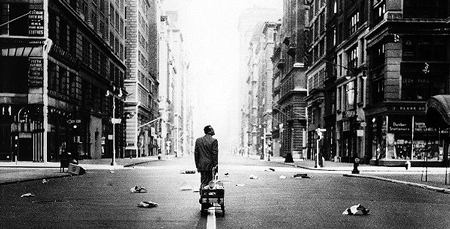

The World The Flesh and The Devil's compelling scenes of a modern city completely abandoned have since been repeated ad infinitum, but its novelty in 1959 needs to be kept in mind. For the record, Will Smith's I Am Legend seems as much a remake of this movie as it is of Richard Matheson's post-apocalyptic vampire tale. The scenes of Harry Belafonte wandering in the litter-strewn streets of New York are actually more convincing. Less is more -- the sight of a pair of buses crashed in the middle of an avenue makes an impression equal to reels of CGI effects. A few matte paintings augment intriguingly realistic views of Belafonte gazing at the landmarks of lower Manhattan. None of this was easy to film. 1 The first half of the movie is extremely interesting as it offers a wealth of detail about what life might be like for a Robinson Crusoe marooned in a major metropolis. Ralph listens to tapes of the last radio broadcasters dying, and cries silently; soon he's acting oddly, as if he might go mad. Belafonte's suppressed loneliness and distress in these scenes is very convincing. The similar films Last Woman on Earth, The Last Man on Earth, Omega Man and The Quiet Earth all recycle ideas and incidents from The World The Flesh and The Devil. Although it's never spelled out, many viewers assume that Ralph is staying out of the buildings to avoid the corpses that we presume must be inside. As only a few days have been passed since the mass kill-off, this inconsistency has to be chalked up as a big question mark. MacDougall's conveniently self-neutralizing atomic gas is a definite screenwriter's crutch, a nuclear threat as fanciful and irrational as the "Great Whatsit" from A.I. Bezzerides' Kiss Me Deadly. But MacDougall's atomic theme is mainly an attention-getting short cut for what is really an artsy allegory, an undisguised message picture about civil rights. Its approach to race relations seems tame now but was certainly controversial in 1959, when prevailing tradition and a number of state laws were solidly against mixing the races in any way whatsoever. Belafonte was and still is a major civil rights proponent in show business. He hit this issue hard in both of the pictures he produced in 1959 (the other was Robert Wise's Odds Against Tomorrow, a crime caper that goes awry due to racial prejudice). Belafonte was far more outspoken about race inequality than the "nice" Sidney Poitier, yet his film aims to be persuasive, not confrontational. While Sarah seems eager to become Ralph's lover, it is the black character that resists, nursing a grudge that could be described as racist. The initially easygoing Ben Thacker claims that he resents Ralph only because he's younger. This is akin to making a movie about vicious wolves, in which a sheep turns out to be the agressive party. Could these evasions have been included for commercial purposes, to try to keep The World The Flesh and The Devil from being banned from movie screens in the South? Or would no movie carrying a 1959 Production Code seal be allowed to deal with the issues -- sexual, religious, racial -- brought up by the movie?

Viewers tend to remember the film's first half more clearly, before the narrative becomes a forced love-hate triangle. Belafonte and Stevens are excellent, with Stevens particularly good at expressing an ambivalent attitude toward the future and her status as a desired female, presumably the hope of the human race. Ralph's uneasiness with the idea of sex with Sarah is implied in a scene where she talks him into cutting her hair. Sarah's clear intention is to provoke Ralph; the scene is a substitute for a sex encounter. She urges him on, but Ralph only grows irritated at the intimacy of the act. He bristles when she innocently uses the phrase, "free, white and 21". Liberal director-actor Mel Ferrer, who acted in the truly inspired race-themed Lost Boundaries, just isn't very interesting as the third wheel in this dour love triangle. The script wants Ben Thacker to be an okay guy, but he comes across as a wishy-washy villain, too gutless to follow through with his threat to kill Ralph. Aware sci-fi fans will immediately peg The World The Flesh and The Devil as derivative of two earlier End Of The World movies. 1951's groundbreaking Five has a similar "Adam & Eve" love triangle plot, with a passive fellow and an arrogant European competing for the attention of the leading lady (ironically, Susan Douglas of Lost Boundaries). Roger Corman replayed the same basic idea, adding a monster and making the Biblical context overt, in his micro-budgeted Day the World Ended. Like both of those pictures, The World The Flesh and The Devil dresses up its cautious liberalism with Biblical overtones. Ralph pauses in a church at one point. When Ben stalks him through Manhattan with a high-powered rifle, Ralph pauses meaningfully before a United Nations peace plaque, which Miklos Rozsa's dynamic score heralds as if it were Moses' stone tablets. Unfortunately, the visually stunning finish is also a cowardly dodge that fails to resolve the story or do justice to its progressive theme. The trio's situation just doesn't seem that much of a problem: with so few people left alive, you'd think three consenting adults could figure out their own compromise with the now-irrelevant social niceties of the past. Frankly, the obvious solution is that they should run to the library and look up the phrase "ménage à trois". The final text title, "The Beginning" could be taken from any number of supposedly less cultivated sci-fi thrillers. All that's needed is a Jack H. Harris question-mark. Director MacDougall clearly defers to his cameraman and films many dialogue scenes from an uninteresting middle distance. Street encounters look flat and the coal mine that traps Ralph seems like a cavern. Other angles are far more interesting, suggesting that MacDougall (or his 2nd unit director, or his cameraman) had a real eye for composition. The visuals veer between impressive shots of the Statue of Liberty surrounded by empty water, and much more mundane settings back in Culver City. When Sarah and Ben go on a picnic, they sit down before the stone bridge from The Dirty Dozen, -- a familiar landmark on the old MGM back lot. MacDougall can't resist indulging an in-joke with Sergei Eisenstein's famous 3-lion cutting sequence from his silent Battleship Potemkin. When Ralph rings a church bell we see a series of jump cuts between a number of lion statues. The sculptures appear to "animate" to become one lion waking and roaring in response. In 1959, only hardcore hardcore foreign film fans would likely make the connection. Woody Allen would later spoof this kind of copycat noodling, when a Potemkin- like baby buggy bounces down some stone steps in his farce Bananas. For the record, Harry Belafonte's Ralph also witnesses a baby buggy rolling down the sidewalk on its own, blown by the wind and rain.

The Warner Archive Collection DVD-R of The World The Flesh and The Devil is a very good enhanced B&W transfer of this CinemaScope production; the scenes of New York streets empty of life have always looked really impressive. Miklos Rozsa's orchestral score dominates the film's many non-speaking passages. The composer skips back in his repertoire past his epic themes to the mood and drive of some of his better film noir scores, like Double Indemnity. The pounding cadence at the finale allows Rozsa to mark almost every one of director MacDougal's "significant" cuts with a strong note. The WAC presentation comes with an original trailer, which strikes all the right notes -- mystery, spectacle, star power -- stumbling only once to shoehorn in a bit of Belafonte singing a calypso song! The World The Flesh and The Devil is a must-see for science fiction fans. Only six months later, it was eclipsed by the much bigger On The Beach, a movie about atomic doom that doesn't switch subjects in mid-film.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

The World The Flesh and The Devil rates:

Footnote: 1. In 1997 I was lucky enough to talk to producer Robert H. Justman (Star Trek), who was the assistant director for this film's New York location scenes. He said that they filmed the six or seven minutes of Belafonte (and later, Stevens and Ferrer) wandering the "empty city" by filming in the immediate pre-dawn. The city would let them block off a couple of streets between 4 and 5:30 AM. They'd rush up and down the street distributing trash and "abandoned" vehicles, and get only a couple of minutes of the actors in motion, sometimes only one or two takes. Even then, they'd have to scramble to clean up their mess because city vehicles and impatient "early birds" would be waiting for the barriers to come down. Times Square was a different problem, and was shut down for a few minutes -- traffic, pedestrians and electric signs --- for a few minutes later one morning.

Other shots obtainable without stopping traffic were of course easier to get -- for "up" angles of Belafonte against tall buildings, just keeping pedestrians a few feet away did the trick. The major dialogue scenes with Belafonte and Stevens at street level were filmed on the MGM lot. Matte artist Matthew Yuricich provided skyline shots free of smoke and steam from buildings, birds, airplanes, etc.

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with reader input and graphics. Also, don't forget the 2010 Savant Wish List. T'was Ever Thus.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||