Stuart Galbraith IV: How did this book come about?

Steven Bingen: To say that I've always been a film buff would be accurate and obvious. But it would also be irrelevant. I didn't grow up in LA, so Hollywood seemed a world away from my real life. Perhaps because it all seemed so alien, I found myself particularly obsessed with movies where a character would go to Hollywood and crash the gates of a studio. You know, Hollywood or Bust (1956), or The Errand Boy (1961), or Anchors Aweigh (1945), pictures where Jerry Lewis or someone would find themselves inside a movie lot and experiencing its marvels and mysteries. But material about these studies themselves, as opposed to the movies made there, seemed almost conspiratorially vague. To this day, if you dredge up any book written about the Hollywood studios, you'll find someplace inside, amidst all the text about the films and about the stars that studio created, a single sentence or a paragraph (with one aerial photo, maybe) about the physical place where these pictures and stars came from. And that paragraph, will always say how amazing, how wondrous and Oz-like this place was - and then go back to its discussion of Judy Garland's personal problems not describe it further!

This was inexplicable and maddening. Think about it this way. If a book has the words "Paramount Studios" on its cover, well, shouldn't there be more than a paragraph inside about "Paramount Studios?" I remember thinking after the 8th or 9th "Paramount Studios" book, that if a farmer had bought a manual about raising tomatoes, only to find that said manual was really about the tomatoes themselves, the politics of raising tomatoes, and how much people enjoyed (or didn't) eating those tomatoes. Well, he probably would have been justified in returning that book to the feed store and asking for his money back! But no one but me ever questioned or even seemed to notice that there was something odd and mysterious about any of this. This mystery, and I didn't know what else to call it, eventually was one of the factors that brought me to Hollywood. One of the first things I did when I moved out here was to drive out to see the physical lots of all seven of the majors. I spent days walking their fence lines and peeking through knotholes in those fences. Oddly, I felt like I'd been to all of these places before. And onscreen at least, I really had. We all have. So my interest in movie "studios" only deepened.

Photo: Randy Knox

Eventually, years later, and probably because of this same interest, I was working as a staff historian at Warner Bros. One day I was walking past the front desk and I heard the receptionist talking to a stranger who was clutching a set of enormous three-ring notebooks. This person was telling her that he was in possession of some of the only [extant] reference photos of the old, long since demolished MGM backlot, and that since Warner Bros. then owed much of the library of films made on this property, he was wondering if we might be interested.

SG4: Ha!

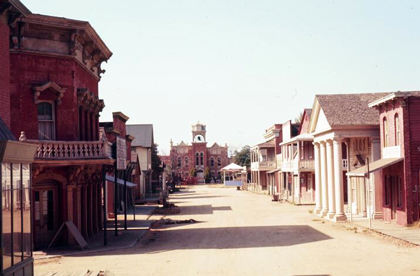

SB: Might be interested! I couldn't speak for Warner Bros. but, personally, this was exactly what I had wanted to see my whole life. I remember helping him carry his notebooks over to the coffee table in the lobby and brushing the two-year-old magazines away and diving into these amazing, unseen-by-anyone-in-decades pictures. It was like climbing over those studio fences I had walked on those first days in LA and finally looking around inside. The owner of the notebooks, Stephen X. Sylvester, explained to me that he had gotten this collection from an MGM employee who had rescued them from a dumpster at the studio! They had been taken in the 1960s as an aid in renting the facility's backlot sets to outside productions, and as such, almost inadvertently consisted of a "virtual tour" of the property as it had been at the time.

Stephen explained to me that he was a filmmaker and historian who, it turned out had actually been to the studio, twice, in the 1970s before the backlot had been torn down. As we looked at the pictures, I remember him telling me that the day after his first visit to MGM his parents had taken him to Disneyland - which in comparison had seemed small and disappointing! This made me wonder, once again, about why the story of the studios - the studios - had never been told. I told Steve what I had been thinking, and he said that he had been obsessed with the same idea since that first, life-changing visit to the lot all those years ago.

SG4: What about the book's other co-author?

SB: Well, oddly enough, it turned out that we had a mutual friend, Michael Troyan, who had recently published A Rose for Mrs. Miniver: The Life of Greer Garson, which is the best book ever written about an MGM star. Mike contacted me about a book about that studio at about the same time as my meeting with Steve, who it turned out, Mike even already knew! It just seemed like fate, or at least very good timing, that the three of us should collaborate together on such a book.

SG4: You're not only an employee of Warner Bros. but also a former tour guide there who knows that studio inside-out. That, coupled with the fact that most of Warner Bros. still stands while most of MGM does not begs the question: Why not Warner Bros. first?

SB: Well, as I said, when I got to Hollywood, I spent a lot of time exploring the studios. Sadly, they have all been compromised and truncated and downsized, and their backlots have been turned into parking lots and theme parks. But my point is that you can still visit them. You can climb the fence and look around inside these places, even today. Well, at least until security comes looking for you. This is true for all of the majors except for MGM. Because I've never been there, because most of their acreage is now condominiums and suburbs, lost forever as it were, is part of why I think it's all so romantic and haunting. Maybe it's true that lost causes are the only ones worth fighting for. To me MGM is a synonym for Camelot or Shangri-La. We can imagine it. We can see it in a thousand movies. But we can never actually go back there. Which is what I've spent my life imagining doing.

When the book was in galleys I remember remarking to the publisher that we were all putting a considerable amount of time and effort into designing the world's first guidebook to a place which readers would never actually be able to visit. He probably didn't think this was as ironic as I did.

SG4: It would be funny if this were to turn up in the Travel Section at bookstores!

SB: Well, that would be strangely apt, but I'd very much hate to have to deal with readers who bought in that section when they got off the bus in Culver City!

SG4: The organization of material is unusual. Rather than a typical coffee table-style book of loosely organized photos, you decided to sort it out almost literally building-by-building. How did that happen?

SB: Again, that was a conscious decision that ties into the idea that this book is your guide to a solid and very physical place. The text is laid out as an actual "tour" corresponding exactly with the (included) studio maps, and with the departments and sets exactly in the order you would have seen them in if you had stepped through the front gate and then walked the place end to end. Originally I wanted to go even farther. I picked a specific date in the year 1960, which was consciously chosen because the major the sets were all still intact then. I wanted to explain what a visitor would have seen shooting that day and how the lot would have looked and felt as the dream factory revealed its secrets to him. Fortunately Steve and Mike talked me out of that one. But I didn't give it up without a fight. And a lot of that "tour book" atmosphere is still there, in a more general sense.

SG4: It seems like what you were doing was a massive jigsaw puzzle, trying to place structures on backlots that were constantly evolving, changes that were being changed, etc. What was the process like, going through photos trying to place and date them?

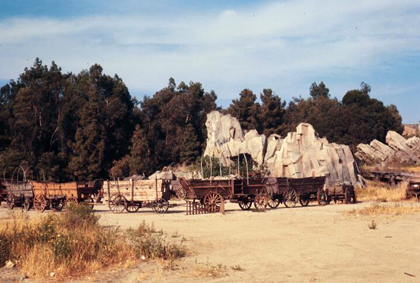

SB: Sets were built and torn down with alarming frequency in the earliest days. The original backlot which, sure enough, was at the back end of the property, and which was described for the first time in print using that phrase, was nearly impossible to document. That backlot was so small, never more than about 10 acres, and yet we documented more than a dozen sets with separate histories and identities on that tiny property alone. When the studio moved their backlot across the street some of these facades moved as well. A set called Waterfront Street, which was originally built on a man-made lake, crossed the street, confusingly taking the name with it, although it no longer fronted any water. These later sets tended to be more permanent. Some of them stood for decades. They survived movies and moguls and earthquakes and television. Their longevity and was due to the fact that art directors quickly discovered that changing a camera angle, or the language on a sign, or the costuming on an extra could turn a Greek Street in to an Arabian Village or Moscow into the Pacific Northwest. Steve in particular, perhaps because he had actually been there, lucky devil, got very good at identifying a street from a still or from watching a film - despite the really ingenious ticks that would be used by the studio to hide its identity. But sometimes, even with blueprints, maps and detailed reference photographs, when we would consult the daily production reports we'd still be surprised, sometimes astonished, to discover that a certain set had been used a certain way in a certain picture. It's somewhat sad that modern Hollywood has largely forgotten this. I spoke to more than one modern art director who told me that any location in the world could be created successfully in a studio and with better and more creative results than on an actual location. Which of course is something Hollywood had been doing since the beginning.

Photo: Brainard Miller

SG4: How did MGM's lots differ from the other studios'?

SB: Unlike any other studio MGM was largely designed by one person. Cedric Gibbons was the head of the Art Department under Samuel Goldwyn, before the merger. After the formation of MGM in 1924 he stayed on for decades and was credited as one of the art directors on every film the studio created. He still has more on-screen film credits than any person in history in any category. His whole life has been reduced to a trivia question today because he designed the Academy Award "Oscar" statue as well, but Gibbons was responsible for the physical look of most of the 20th Century through his designs for MGM pictures, which were wildly influential both at the time, and now, when we look back at his era. From Art Deco, which he was the first to popularize on-screen, to the small town America of Andy Hardy, Gibbons's sets gave MGM's pictures and its lot a unity that no other studio ever had. Everything inside the Gibbons-designed studio gates, from the backlot to the screening rooms to the commissary to L.B. Mayer's white inner office - all of it owed their physical look to Cedric Gibbons.

SG4: What are some of the big misconceptions about MGM as a studio?

SB: When we started interviewing people who were there, we were surprised that they all agreed that the opulence and luxury which everyone assumed came with working at MGM was largely an illusion. Stars were pampered, to be sure, but with the exception of Marion Davies, who had a dressing room bigger than a roller rink, most of them operated out of rather sparse lodgings. Working at MGM itself was considered to be reward enough, a sign that one had reached the very top of one's chosen profession. Other studios tried harder because they had to, whereas MGM had nothing to prove. At MGM all the splendor was on the screen.

SG4: I'm reminded of movies about movie-making where you always see bustling activity between the stages, extras dressed as knights, camels being led around and all that.

SB: Indians eating lunch with cowboys in the commissary, that sort of thing? One likes to hope that it was really like that. And there are certainly enough stills and Hollywood-set movies documenting this sort of thing. But I suspect that when it really happens, and it does, that the people involved, those costumed extras and that person leading around that camel, would have been well aware that they were actually enacting a most beloved Hollywood tableau. The other day I was walking a studio street at Warner Bros and sure enough, I noticed that I actually was talking on my cell phone! And I remember thinking, even as I was doing it, how Hollywood-ironic and funny that was. All of which, of course, made this moment no less real, and no less of a cliché.

SG4: Warner Bros. now controls MGM's library, mostly, while the property is owned by Sony, and the MGM name by what's left of MGM. Did you have to jump through a lot of legal and corporate hoops clearing rights to use photographs and to get everyone to sign off on this project? In what ways were they helpful (or not)?

SB: We didn't need MGM's permission because all of the assets we were accessing are Warner Bros. owned. Both MGM and Sony cooperated, if not corporately, than individually, in that I made some wonderful friendships with employees at both companies who contributed stories and photography. My relationship with Warner Bros., one would think, would have given me an edge in licensing their photography. And it did, I suppose. I certainly had access to materials beyond even what Steve brought to the project on that first day. And I'm very grateful that management at Warners saw the value of this project early on and let me publish these materials, most of which had never been used anywhere before. But because I was on the "inside" there, I had to tread very carefully. Just getting a studio lawyer to put aside his million-dollar workload in order to draw up a contract from which WB didn't stand to ever collect a dime, involving another studio, and for the sake of another employee yet. Let's say it was a bit of a struggle. But they were wonderful. And I'll always be grateful to everyone involved there that ultimately indulged me on this. I still owe a lot of favors.

SG4: Several MGM veterans contributed some of their memories to your book. What was it like talking with them?

SB: The best stories and anecdotes about the lot without fail came from the below-the-line workers, or even from outside people who as children used to climb the fence in order to explore the property. We kept trying to get to Elizabeth Taylor to contribute something, but could never quite manage to swing an interview. Eventually it occurred to us that for someone at her level, even though she worked on the lot for decades, there probably wouldn't have been much opportunity for her to poke around inside the facades or explore the property anyway. And I'm not sure if Elizabeth Taylor, who became a major star when she was a very small child, would have seen the place as at all remarkable if she had. I mean, think about it, what basis for comparison could see have had? The other side of the coin was Debbie Reynolds, who came to the studio at 19 after an exceedingly normal childhood, and so could well appreciate the sublime oddness of what was going on all around her. I suspect that, in its way, the place haunts her to this very day, just as it does us.

SG4: One thing I like about the book is that it's not just "MGM: The Wizard of Oz and the Arthur Freed Unit." The book goes into a lot of detail about the physical origins of MGM, the early silent period, and later as the studio goes into decline, its use by TV shows like Twilight Zone.

SB: We tried to discuss the films, whatever their merits, only in the context of how they affected the studio. There is a certain snobbery in film writing about which individual pictures are worthy of discussion or admiration. But go down to a set when the product is actually being made. If you talk to the guys on the crew, they'll tell you tell you that the memorable pictures for them are the ones that affected their lives while they were being made. Some of these people don't even bother to see the movies when they're done. For them, the final product isn't the point at all. It's exactly the same with the studio. In 1950 MGM built an enormous set with a waterfront pier and several city blocks of detailed New England period architecture for a proposed Clark Gable picture to be called The Running of the Tide. For various reasons the movie was never made. But the set showed up in the studio's product for the next 20 years. So in the history of the facility, this unmade picture was more important than The Wizard of Oz! One of our reviews criticized us for discussing too many "forgotten" films, which I think rather misses the point.

SG4: Really? That sounds like the Richard Schickel approach to film scholarship: if it's lost then it ain't worth writing about.

SB: Infuriating isn't it? We took the other tact. We tried very hard to include not only famous movies which our readers would recognize, but also films most of them probably wouldn't. And to make sure to also include episodic TV, commercials, short subjects, even music videos. Our story wasn't about the product but the factory. We used the product only as a through line to illustrate the story we wanted to tell.

SG4: I was also pleased to see a lot of photographs and frame grabs not only from That's Entertainment!, but also The Phantom of Hollywood, a cult TV movie filmed on the lot almost literally as it was being torn apart. That seems to have been a big influence on you just as it was for me.

SB: Well, that plays into my point. I mean, besides you and I and a few other sleep-deprived film buffs, how many people even remember that movie? TV Guide didn't even bother to review it the week it premiered! But that film was vastly important to our story. And while we're on the subject, I have to mention that in some very odd ways, Phantom of Hollywood is also perhaps one of the most, well, subversive movies ever made!

Photo: Brainard Miller

How much do you remember of the plot? It's usually dismissed as something of a knock-off of The Phantom of the Opera, what with a deranged and disfigured actor killing off trespassers and studio executives trying to destroy the movie backlot he was living on. But sometimes I've wondered if the story also wasn't a bit of a meditation on the Manson case, which hadn't been over long in 1974 when the film aired. Charles Manson, remember, specifically targeted the Hollywood community when choosing his victims, and people forget that he was finally apprehended while hiding out in an abandoned movie backlot. All of this horror and guilt must have been percolating in people's minds, writers and actors' and executives in the film industry at the time. And like you said, it's important to remember that this film came out at the exact moment when actual MGM executives actually were destroying their actual studio backlots. And the script is sympathetic not to studio management - personified by an ascot-wearing studio chief played by Peter Lawford - but to the Phantom himself! (The Phantom is played by Jack Cassidy, who in this film it always seemed to me to be rather charmingly channeling John Barrymore!)

So this little footnote of a picture is one of the few Hollywood movies to take a stand on anything. Or at least to take its stand not years, not decades after the fact, but at the moment the issues it concerned itself with were actually happening. And the position this movie, this "MGM movie" dared to take, was a condemnation of nothing less than MGM itself. I mean as odd as it sounds, the people who made this film were firing their barbed arrows at their own bosses! And just in case anyone still missed the point about who their target actually was, they even cast an actress named Skye Aubrey as Lawford's daughter. Skye Aubrey was, in reality, the daughter of Jim Aubrey, who was running the studio at the time, and who was personally responsible for the destruction of its backlots. Amazing! As far as poison pen letters go, Sunset Boulevard isn't nearly as audacious as Phantom of Hollywood is.

SG4: Another thing I always wondered about that the book explains quite well is that the different studios, to say nothing of independent production companies, often shared or rented facilities elsewhere, so that, for instance, a movie from Universal might use a tank at MGM for a couple of shooting days. Could you talk about that some more?

SB: You're right. I think we always assumed that in the days when studios were autonomous factories with their own product and assembly lines, that there was little sharing of facilities. We all know that the moguls used to trade their talent back and forth like poker chips, but the truth is that backlots would be bartered the same way. Consequently alert viewers can spot the set used in Paramount's The Heiress (1949) in Charlie Chaplin's [United Artists release of] Limelight (1952). Or the MGM's St. Louis Street in RKO's The Farmer's Daughter (1947) or in Fox's Cheaper by the Dozen (1950) or even, just before it was demolished, in an episode of Universal's Night Gallery. Without dipping too deeply into murky cinematic pretension (hopefully) it seems to me that this unity, these identical visual cues from picture to picture across the decades, tie these films together as much as had they shared a director or an actor. Why hasn't anyone ever noticed or commented on this?

SG4: Absolutely! For instance, Alfred Hitchcock's movies filmed when he was at Paramount have a completely different look from his ones at Universal or Warner Bros. His style is consistent but the environment changes.

SB: I wonder, even for someone as meticulous as Hitchcock, how much of this was intentional and how much was subliminal? Hitchcock's pictures at Universal, starting with Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and running through The Birds (1963) at least, had an insular, small town sensibility that might have come from the feeling of the factory where these films were mounted and/or filmed as much as from their scripts. Universal, as a place to work, probably really was a bit suburban and isolated in those pre-MCA days.

SG4: Certainly Universal's Colonial Street helped define postwar suburbia from Leave It to Beaver and The Munsters through Desperate Housewives, just as St. Louis Street at MGM symbolized a bygone America of earlier in the century.

SB: A person could speculate about just how much of the small town or suburban nostalgia we all seem to be hardwired with comes from our lives, or our parents' lives, and how much of it actually originates in these movies shot on these sets? Or maybe we all absorb it at Disneyland? And remember that even Disneyland was itself was created by a film producer and designed by a studio art Department!

SG4: Hal Roach Studios was just down the street from MGM. Was there any kind of particularly special relationship/crossover between those two companies in terms of sharing space? Given that shows like Twilight Zone were shooting simultaneously at MGM and Roach in the early-1960s, just before the Roach lot was torn down, I'm surprised MGM didn't try to absorb the real estate.

SB: Because Roach and MGM were long linked in a business sense, and geographically, it would have seemed ideal for that to have happened. But Roach Studios took down their shingle and locked their doors in the early 60's and that was just a little too late for MGM to be interested in land acquisition. Their own financial problems had already started. 20th Century Fox Studios just a few miles north up the road from MGM itself, would sell off much of their own backlot the following year, and neither MGM, nor any other studio showed any interest in acquiring their physical assets either. A pity. I drove out to the site of the Roach lot not too long ago. There is tarnished little plaque across the street from a car lot to mark the spot.

SG4: One thing I found amusing was that many of the surviving buildings have been renamed, sometimes for actors and directors who spent precious little time on the lot.

SB: That's true, and even stars that were minted on the lot have had their names show up in the oddest places. And his practice started when MGM was still there. I believe that they consulted with Marc Wanamaker, one of Hollywood's premiere historians, about what building should be named after what talent. But they must not have listened to his suggestions. Consequently we now have the former Makeup Department rechristened the Clark Gable Building, although, to be fair, it isn't inconceivable that Gable may have stopped by there once or twice to have his mustache trimmed. A long-time dance rehearsal hall now bears the name of that noted hoofer Greta Garbo. My favorite example though, is the case of the old studio schoolhouse, now renamed the Crawford Building, after a great star never particularly known for her skills with children.

Photo: Brainard Miller

SG4: You mentioned Debbie Reynolds earlier. Your book was released at the same time that she has was basically forced to sell her massive collection of costumes and props, the core of which is from MGM. She tried but never succeeded in launching a big Hollywood museum celebrating its history. Does Hollywood really care about its past?

SB: Not in any sense beyond preserving the films themselves. Hollywood takes a lot of heat in that regard as well, but dollar for dollar they do more for film preservation than any other corporation would in a similar situation. For example, can you imagine Ford Motors laying out cash to restore old cars they might have manufactured in the 1930's? OK, maybe that isn't a good example, because you could make the argument that Warner Bros. still owns their old product and Ford doesn't. But how much profit is there in restoring, and then maintaining fuzzy George Arliss pictures from the 1930's anyway? I can tell you that, sadly, in a world where many adults find it inconceivable to watch a black & white movie, there isn't much. Yet The Studio is expected to preserve a legacy the people who work there now didn't create. A legacy which these employees largely don't understand, and sadly, can't personally reference or remember. Hollywood gets a failing grade in caring for their past in any other sense. Do you know that the last remaining prop shark from Jaws (1975) is rotting away on top of a pole in an auto wrecking yard in Sun Valley? This was a movie which affected, on a very personal level, an entire generation of moviegoers. But Universal apparently though so little of it that they let the wrecking yard have it for free when they came to cart off a truckload of scrap metal. It's inconceivable that Paris has a major museum devoted to the moving image but Hollywood doesn't. The problem is that in Paris, and in much of the world, movies are an art. In Hollywood movies are big business. Yes, show... business. And nostalgia and business have never been comfortable bedfellows.

SG4: Yeah, it's like: In newspapers where does one find the weekend box-office reports? In the "Arts" section.

SB: Or for movie reviews and analysis, just look in the business section!

SG4: Should studios be compelled to preserve their backlots and other culturally historical landmarks, or is it a business simply too liquid to accommodate such long-term preservation and care?

SB: My gut instinct is to roar "yes!" But I understand that even during years when a studio's product makes money, the profit margin for running the studio facility itself is razor thin. Outsiders, even Hollywood savvy outsiders, don't understand that an entertainment company's factory has to make a profit, just as its product does. And that these are two different and largely unrelated things. One of the glories of the old studio system that is never remarked upon was its relative simplicity. The same people and departments worked on every film that came down the pipeline. If a picture needed a set or a costume or a matte painting created, there was a department somewhere on that assembly to do it. Today, all of these services are fanned out, and charged out, separately. If the studio producing a film has a department capable of creating these things, that department has to submit a bid along with outside contractors. This bid is accepted (or rejected) by someone in a production office somewhere, created for this one picture, and staffed by freelance people who will themselves be laid off when the film wraps. And the same wasteful and expensive process will start all over again for the next picture to come along. This is why, in modern Hollywood, you often see Warner Bros. films shot at Paramount or Fox, or in Bulgarira or Canada. Every acre of real estate on a modern studio lot has to be profitable to justify the real estate it occupies. The key to preserving Hollywood's backlots, which I think are as important in our popular culture as the films made there, doesn't lie in putting these sets under glass and giving them historical landmark status - that would just tie the studios' hands as to continuing to utilize them - but rather in finding ways to make it more viable for studios to profit from them. We need incentives or tax breaks or legislation. We need to do whatever it takes to keep production happening on these sets, which is the very best way to contribute to their profitably and to continue their legacy.

Photo: Author's collection

SG4: What part of MGM do you achingly wish was still around, and of what survives what do you like most?

SB: It would be impossible to choose one spot because the charm of the place would have been, for me, the ability to walk from an 18th century French village, into the American West, and then to turn a corner and explore a WWII military base nestled alongside a Jane Austen style estate and garden, which itself would have been adjacent to a dangerous-looking south American jungle! This weird, whimsical, whirlpool of architecture, which F. Scott Fitzgerald called the "torn picture books of childhood," still strikes me as wonderful and magical and sinister. Just like a fairy tale. Sony has spent a lot of money and did a beautiful job in restoring what remains. But the similarities with the old MGM are mostly just chronological.

SG4: Since its publication have you heard from any of MGM's former employees?

SB: I've been worried that former MGM-ers would come out of the woodwork and shout, "that weren't how it were." But the response from people who were there has been overwhelmingly favorable. I still imagine getting a phone call from someone someday who has all the answers to all the questions we could never find though. How wonderful and how terrible would that be?

SG4: Will there be books on other studios in the future?

SB: I hope so! I thought with this book, I might be able to exorcise once and for all my lifelong backlot obsessions and compulsions. But each studio has its own history and legends and ghosts. What happens next will largely depend if any of these ghosts want to talk.

Reader Responses:

1. From Malcolm Alcala, 7.30.11:

Hi Glenn. Please relay my thanks to Stuart for the article/interview regarding the MGM backlot. On Easter Sunday in 1975 my friends and I jumped the fence in search of the things we had seen in The Time Machine, The Twilight Zone and anything else we could recognize. The big surprise came when we came upon the great wall and sacrificial spot where the (new) Bride of Kong was going to be tied. We had absolutely no idea they were doing a remake of the movie. But what else could it be, eh? We had a glorious 2 1/2 hours of walking around the property. We were finally caught in the New York brownstone area, which seemed fitting somehow.

That's the short version. It was one of the most fun days I've had in my entire life and I think about it often. I'll have to get the book to refresh my memory of all the things we saw. If only I had been taking photos in those days. -- Malcolm

2. From Craig Reardon, 7.29.11:

Glenn, I loved Stuart Galbraith's interview with Steve Bingen. Brad Arrington had sent me a link to an ad for that book months and months ago, and it seemed great, but I'd had a horror of it turning out to be skimpy or cheapjack. It's great to have more confirmation that it is a good book via Galbraith's appreciative reactions. I'd sent the link off to John McElwee, and much later I asked him, "Hey, did you buy that, and am I indirectly responsible for sticking you with a lemon?" He assured me it was no lemon, but a lemon meringue pie, so to speak.

I identify with everything Bingen says, especially his remarks about autobiographies of Hollywood people. They always concentrate on "And then I did...", but there is never any evocation whatsoever of the physical realities of a department or a lot. I've made these remarks almost verbatim in past communications. It's a HUGE part of the fascination film fans have. There are still, as Mr. Bingen knows very well, some absolutely recognizable pieces (portions of streets and their facades, standing sets, etc.) at Warner Bros. where he works that date back to the 1930s. So it isn't merely that the lot still exists. That's a little thing, really, in terms of what fans are really fascinated by. What's really fascinating is that some of those goddamn SETS still survive, intact. I've been inside the famous NY brownstones that used to have gangster sedans screeching past them spraying 'lead' in the '30s, and appeared in Life With Father and a million other WB films. What do I mean by "inside"? Aren't they just fronts? Answer: of course, that's just what they always were. But, to be INSIDE them is to confirm that they were built 80 years ago. It's so obvious. There are gauges of timber used that are no longer milled that way (e.g., true 2x4s.) There is also damage and wear that attests to the relative 'antiquity' of these constructs, probably due to the incursion of water and birds, etc., over the decades. Ironically, many of the standing stages at Warners which are just as old are almost as good as brand-new inside because of the fact they've been protected from the elements all this time. The catwalks, the walls, etc. It's a fascinating subject to any true movie fan hopelessly in love with the old movie era. -- Craig

3. From Jon Paul Henry, 7.30.11:

Glenn -- A fascinating interview from Stuart. I used to try and identify bits of backlot when I watched TV shows in the 60s. I also got pretty good, after a while, at spotting bits of older features edited into shows like The Time Tunnel (which should probably have been re-titled "Rest Home for Old Movies").

I really like it when you open your column to interesting features like this. Makes it kind of like a magazine. Cheers -- Jon Paul

Text © Copyright 2011 Stuart Galbraith IV

DVD Savant Text © Copyright 2011 Glenn Erickson