|

|

|

|

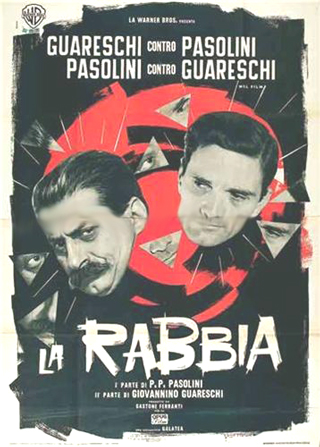

After the demise of NoShame, a video company that specialized in interesting, unusual Italian films, I didn't expect another company to take its place. I think we've found the replacement in the Rarovideo label, which has opened these eyes up to previously unremarked pictures like Adua and Her Friends. This time around we've been graced with a true rarity, restored by the Cinematheque of Bologna. The "official story" goes like this. In 1963 an Italian producer hit upon a great film idea suggested by "dueling editorials" in political magazines: make a film about the political problems of the world in two parts, inviting celebrated leftist and right-wing artists to independently create side-by-side film essays illustrating their political points of view. The producer could thereby turn his access to an enormous library of film clips into a commercial product. Hired to express the liberal point of view La rabbia (The Anger) was the Marxist intellectual poet and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini, one of the most controversial men in Italy. The opposing conservative point of view is provided by Giovanni Guareschi, a political cartoonist and humorist and the celebrated screenwriter of the popular, reactionary "Don Camillo" film series. In actuality, the film came about quite differently. Producer Gastone Ferrati originally hired only Pasolini, but didn't like the 100-minute film that Pasolini turned in. He cut Pasolini's essay film in half and reached out to Guareschi to come up with an opposing viewpoint. Pasolini agreed only reluctantly: he didn't consider Guareschi a real conservative man of letters but a populist demagogue who simply harped on the same old conservative values. Guareschi's Don Camillo film series, for instance, is about a two-fisted priest who talks to Christ through his crucifix, and typically opposes various exponents of liberalism and corruption. Pasolini was even more furious when he saw the finished film of La rabbia, and tried to have his name removed. In his opinion Guareschi's half contained nothing but ugly, hateful propaganda. The final film was released only in Italy, and then only for a short time.

Pasolini's 50-minute film comes first, and then Guareschi's. They were reportedly made separately, with no communication between editorial teams; the fact that the two filmmakers cover some of the same material can be chalked up to the news film at their disposal, and not any ideological overlap. The points of view couldn't be more different, which makes La rabbia a fascinating study of point-counterpoint political filmmaking. The opening statement that each filmmaker attempts to answer is, "Where does the unhappiness and anxiety in today's society come from? Why are we consumed with fear for the threat of war?" Pasolini's gives his lengthy newsreel collage not a standard commentary, but a poetic narration. The connection of images and words is quite interesting, considering that so much of the poetry mingles with the visuals rather than explains them. Pasolini decries modern ways that are corrupting the working classes, and laments ongoing military oppression as the pressing problem of the post-war period. We see film clips of the Hungarian revolt, but most of the Cold War content praises the Cuban revolution, Algerian independence and the retreat of colonial powers before the spread of socialism. The 50s and early 1960s are an era of rejoicing, Pasolini feels, for the black men of the world. For the most part Pasolini is not overly negative on America. His strongest poetic material is a eulogy for Marilyn Monroe, a quasi-abstract ode to innocence in the modern world. Pasolini finishes with hope for the future as represented by Titov's space voyage. We see the triumphant Cosmonaut marching to be greeted by Khruschev, and Pasolini invents a poetic statement that Titov is reporting about a united world soaring above the barbarity and inhumanity of the past, including that of the Communist regime. Pasolini gets an "A" for artistry but a "B-" for communication. Surprisingly, little of the newsreel content has become obscure; we recognize most of what we're seeing. Pasolini interpolates paintings and other artwork without identifying its origin. Some of it is in color and some is little more than squiggles on paper. Editorially, this first half of La rabbia is not very attractive. Much of the arcane docu footage accessed by Pasolini is of iffy quality or taken from over-duplicated sources. To illustrate his passage on Marilyn Monroe, we simply see magazine layouts with her image. Other photos are difficult to read, or have magazine creases in them. Pasolini unites the "right word with the right image" even when he has to include substandard images. Guareschi's half of the show is technically much smoother, but offensive from almost the beginning. His only philosophy seems to be anti-change; he leans heavily on the Church as a defense. His narration is an unbroken cynical and sarcastic set of accusations, he reminds me of our own reactionary Al Capp lashing stupidly out at John Lennon. The ex-cartoonist exploits easily found sensationalist news film to illustrate his condemnation of progressive ideas. Twice he returns to footage of cross-dressing men to indict the decadent new world as perverted. The show begins and ends with a riot at a (Parisian?) rock 'n' roll concert, which is given as evidence of the corruption of modern children. The most disturbing footage is apparent purloined coverage of an atrocious Soviet experiment in which a dog has the head (and forelimbs!) of another, smaller dog grafted onto its neck. It's real, but it looks like an absurd medical experiment from a vivisectionist horror film. Guareschi of course provides no context, but informs us that the Soviet Frankensteins' next step is to chop off the original dog's head. We of course wonder if the object is to do the same with humans, giving a "desirable" person a new body stolen from a politically "undesirable" person. Guareschi uses this grossly exceptional, unrepresentative example to smear all science as heretical.

But that's nothing compared to his nearly fascistic political ideas. He mourns the plight of white colonials driven out of Africa, refusing to acknowledge the parasitic nature of colonialism or that black Africans might have a right to rule themselves. To "prove" his point, he tracks a raucous independence celebration with a John Philip Sousa march, making the blacks look all the more ridiculous. If that racism weren't enough, he shows a film clip of a white girl giving a black man a kiss on the cheek, and then criticizes her. Guareschi's look at the Cuban revolution again places inappropriate music against shots of Fidelistas chomping away on a meal of ribs, comparing them to savage monkeys. The hypocritical Guareschi gives us a photo-montage of starlets with impossibly large breasts to deplore the state of Italian culture, and another montage of ridiculous-looking home appliances to slam the invasion of American-style consumerism. Guareschi always looks to the past, obsessing on war crimes not avenged, shots of corpses in the snow and grieving widows. Guareschi ultimately comes off as a wildly inconsistent malcontent. Without any preparation, he reverses course into a diatribe against the post-war world's desire for vengeance. Pasolini's poetic verses avoid blanket accusations, but Guareschi suddenly bites the United States, hard. When showing the Nuremberg trials, he bluntly equates the Nazi war crimes with America's dropping of the A-Bomb on Hiroshima, suggesting that the Allied judges are just as guilty as Hitler's butchers. That's typical of Guareschi's scattershot approach. In a way Pasolini hasn't done his job either, as he's answered the film's thesis question with a tangential poetic ramble. We'd have to study the verses of poetry on paper to evaluate them, as they communicate a mood and an attitude while sidestepping concrete arguments about the real issues of the Cold War, the effects of modernism, etc. Pasolini probably felt that his response was the only legitimate one, that he was making a cinematic-social artwork and not an illustrated lecture. Guareschi's film, on the other hand, is a heap of ill-considered and propagandistic squawking aimed at easy targets, using sensational and shocking film footage to shock and confuse the viewer. It's like Mondo Cane, with the addition of an offensive political agenda. When all is said and done, Guareschi expects his audience to recoil from his bad taste and retreat into the past and the Church. Pasolini builds to a rather soft statement of hope for the future, while what Guareschi really delivers is an admonishment to stop thinking and pray.

We're told in the extras for La rabbia that the film didn't stay in exhibition long, and wasn't revived often. In the '70s and '80s Guareschi's half was shown separately as propaganda for a Trieste-based Neo-Fascist movement. Pasolini's energy was directed elsewhere when the film disappeared, as he was at the time defending himself from blasphemy charges for another of his films. He's quoted as not being surprised, as "nobody is interested in political films". Rarvideo's DVD of La rabbia is a beautiful restoration of what was considered a lost film just a few years ago. One commentator theorizes that Giovanni Guareschi was responsible for mislabeling the original negative as l'Arabia as a perverse joke. The audio is crystal clear. The visuals come mostly from prime-quality news film mixed with odd-lot sources that range from good to pretty bad. The color sequences in Pasolini's half look perfect. Rarovideo includes a wealth of visual and text extras. Pasolini's rare color film La mura di Sana'a is a UNESCO-funded plea for the preservation of an ancient city in Yemen only recently (1964) made accessible by a road built by the Chinese. The city hasn't changed an iota since the middle ages and Pasolini deplores the almost immediate "developments" that are destroying its untouched beauty. Also included are a number of trailers for La rabbia, including two that look to be merely film excerpts. A very long (68-minute) documentary La rabbia 1, la rabbia 2, la rabbia 3... l'Arabia gives film critics, historians and representatives of both Pasolini and Guareschi a platform to analyze and compare the dueling filmmakers to their hearts' content. One spokesman suggests not very convincingly that the C.I.A. suppressed La rabbia due to the outrageously anti-American statements in Guareschi's section. We learn quite a lot about Giovanni Guareschi, an interesting personality who was himself a prisoner of the Nazis in WW2. His political cartoons are often quite clever. That the two men are (or were) able to speak their opinions reminds us that Italy was one of the few countries where socialists and communists were granted equal political rights with monarchists and conservatives. Pasolini himself called La rabbia irrelevant because in his opinion Guareschi's half was cheap propaganda and not a good representation of true conservative thought in Italy at the time. La rabbia still serves as a striking demonstration of the contrasting arguments of the intellectual left and the populist right in Italy. It's certainly more compelling than the later Italian "committed" attempts we've seen to present the leftist viewpoint, as in the tiring drama Open Letter to the Evening News.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

La rabbia rates:

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with reader input and graphics. Also, don't forget the 2011 Savant Wish List. T'was Ever Thus.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||