|

|

|

|

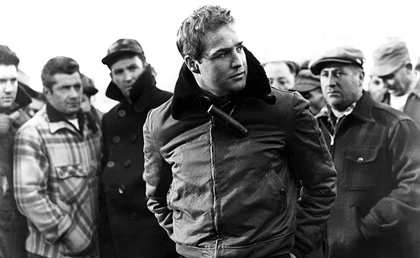

On the Waterfront is an American landmark, now become legend by virtue of the showy performance of its leading man Marlon Brando. The controversial film is also destined to be forever debated for its politics. Its celebrated director Elia Kazan would later frequently state that this tale of an informer against the mob was an expression of his own experience cooperating with the HUAC committee back in the days of the Hollywood commie hunt. The film is exceptional on all counts. The gritty cinematography on the cold New York docks brought a harsh realism to American screens not seen in previous real-location noirs. As with practically all Elia Kazan pictures the acting, directing and writing is of a very high order. This is one of the best Marlon Brando film outings; his pairing with screen newcomer Eva Marie Saint carries even more romantic chemistry than Kazan and Brando's A Streetcar Named Desire. Just the same, Kazan never used quite so heavy-handed an approach to a story, before or after this show. The saga of Terry Malloy comes off as a confused statement of artistic defiance, against Kazan's bitter critics.

On the surface On the Waterfront is similar to other gangland exposé thrillers dramatizing nationally publicized crime investigations, such as the congressional Kefauver Commission. A Federal probe into corruption on the New York docks puts pressure on Union boss Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb), a coarse racketeer. Friendly has already silenced squealer Joey Doyle, an ordinary dockworker, by having him thrown to his death from a rooftop. Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando), a not-too-bright ex-boxer and kid brother of Friendly's lawyer Charley (Rod Steiger) is appalled to realize that he is complicit in the murder. Terry is drawn to the victim's sister Edie (Eva Marie Saint), who is helping activist priest Father Barry (Karl Malden) locate more 'squealers' that could help the Feds rid the docks of racketeers. Terry finds himself in a no-win predicament, forced to choose between loyalties to family and friends, to his new girlfriend, and to what is right. On the Waterfront comes on like gangbusters, leading with Leonard Bernstein's dynamic 'big city' music score and the progressive camera techniques of Boris Kaufman. The film creates a wholly convincing New York environment. We can feel the cold in the docu-realist daytime exteriors, while violent midnight chases make use of expressionistic night-for-night noir techniques. Blending naturally enough into the bitterly cold setting are talented members of the Actors Studio, of which Elia Kazan was a founder. Established superstar Marlon Brando makes a powerful impression, alternately overplaying and underplaying the theatrical Terry Malloy; even audiences with no knowledge of theater craft can see that a lot of acting is going on there. On the other hand, Eva Marie Saint's trembling, emotionally volatile Edie seems a less affected and more honest interpretation. Rod Steiger's Charley is more precise and subtle than Brando, with far less screen time. Although audiences root for Karl Malden's fighting priest, an important facet of the true story on which On the Waterfront is based, the character is both overwritten and overplayed. The "righteous power" of the priest rising with the body of a slain stevedore from the hold of a cargo ship is almost embarrassing. Schulberg and Kazan's Christ/martyr moments in On the Waterfront come close to overwhelming the basic story being told. Johnny Friendly and his gang of mouth-breathing goons, shockingly enough, are not an exaggeration. Friendly's top associates aren't exactly a brain trust, and tyro actor Fred Gwynne's thug almost looks lobotomized. Kazan and Schulberg want the audience to have no difficulty separating the good heroes from the vile villains. Still, it seems a bit much to have Friendly, emotional fool that he is, lose control and threaten violence in a packed congressional hearing room as live TV cameras roll. Although frequently rising to the level of high drama, On the Waterfront is morally no more sophisticated than the average Republic western.

Marlon Brando surely developed an affinity for characters that pass through a 'growth' experience by getting beaten to a bleeding pulp. Terry Malloy nearly comes back from the dead to lead his fellow stevedores to defy Johnny Friendly, stumbling upwards on his own Via Dolorosa. It's a major expression of cine-masochism. As Emilio Zapata in Viva Zapata!, Brando was ambushed by forty riflemen and then figuratively reincarnated as a white horse. His tough-guy heroes in One-Eyed Jacks, The Chase, The Fugitive Kind and The Appaloosa get similar savage treatment. Even in On the Waterfront, Malloy seems to be enjoying his martyrdom far too much. What could be better as a showcase acting opportunity? The film is a masterful combination of theatrics and post-noir docu stylization. But its appeal is marred by its political aspect. Several admirers and apologists in the disc extras refer to Elia Kazan as an outsider, a loner who had to go his own way. On the Waterfront seems to exist to romanticize his actions. But was this extended allegory really necessary? Kazan appears to have been that brand of ambitious careerist that sees the professional world as an unforgiving arena of hard winners and soft losers. At most any level of show business the competition for meaningful work is so intense that even 'nice guys' must ruthlessly guard their interests. Kazan's first attempt at developing a screenplay about corruption on the docks fell apart when playwright Arthur Miller wouldn't distort the story's political content to please the studio. Kazan left Miller behind and collaborated instead with Budd Schulberg, famed author of the ultra-cynical novel What Makes Sammy Run? When it came time to safeguard his career, the director named names to HUAC as instructed, directly betraying his long-time collaborators and associates. Kazan's fame and talent were so well established that, had he defied the committee, he might have rallied enough of the industry behind him to shut down the blacklist. He instead gave the witch-hunters added credibility. That Kazan identified with the 'noble squealer' of On the Waterfront, but Terry Malloy's case for 'justified informing' doesn't even begin to connect with Kazan's HUAC situation. Terry Malloy rats on corrupt gangsters and murderers that oppress workingmen like himself. He chooses to side with the dockworkers and defends their interests, wrapped in the approval of the church and the loving arms of a woman. In contrast, Elia Kazan informed on his own colleagues, writers and other film people already persecuted for their unpopular politics, who had no way of defending themselves when cooperative witnesses threw them to the wolves. The actions of Kazan and his film character don't really align. Audiences have never really understood the film's obscure conclusion. Just what happens? Unable to show Malloy's martyrdom accomplishing much beyond displacing a few Union racketeers, On the Waterfront segues directly from its Christ allegory to a strangely ambiguous finale. The battered Terry Malloy leads his miserable fellows to answer the whistle of the real big boss, apparently a shipping executive. Nothing has changed for the dockworkers as they disappear behind a pair of giant warehouse doors. This final image has been compared to the vision of the equally powerless workers in Fritz Lang's Metropolis, devoured by the jaws of Moloch. It should be obvious that although Johnny Friendly was a crook, his replacement will also need to be a dirty fighter. To get the bosses to pay a fair wage the dockworkers will need a Union that acts just as tough as Friendly's. The movie touches on this realization only in its last ten or fifteen seconds.

The film's most famous scene is Brando's "I could have been a contender" monologue to Steiger's Charley in the back of a taxicab. It certainly is a powerful loser's lament: Terry is just another pathetic sell-out to misplaced values and ambitions. Several critics including Richard Corliss have pointed out that the scene's theme statement about ambition and corruption was done earlier and more eloquently in a classic taxicab speech in another noir classic, Force of Evil. Unlike Terry Malloy, John Garfield's corrupt attorney knows exactly what he's doing when he sells out his ethics to the mob. His stylized dialogue strikes deeper, to the heart of the issue -- the attorney can't understand why people persist in clinging to sentimental ethics in a system that values only material success. The co-author & director of Force of Evil is Abraham Polonsky. Unlike Kazan, he didn't kowtow to the HUAC and was blacklisted. His ethics cost him twenty productive years while Kazan's career proceeded to many more impressive Hollywood accomplishments. I'm glad we have Elia Kazan's films to enjoy, and On the Waterfront is certainly one of his most prominent. But what of the Abraham Polonsky movies that never got made? Criterion's Blu-ray of Columbia's On the Waterfront is a terrific HD transfer of this moody, chilly B&W picture, where we can often see the breath of the players in exterior scenes. Critics in 1954 associated visuals like these with admired Italian pictures considered more "real" than shows with Hollywood lighting. In this viewing I especially enjoyed the Leonard Bernstein music score, which frequently sounds like a warm-up for the dynamic compositions in West Side Story. Criterion or its disc producer Issa Clubb has opted to present the film in three aspect ratios: 1:66, 1:85 and 1:33. An extra explaining the reasoning behind this is not particularly compelling. They admit that the film's official AR is 1:85, which does indeed seem a little tight on home monitors. I'd pick 1:66 as a fair compromise, just as Criterion has. Their main piece of evidence is a published list of 1954 Columbia releases with the note that they are screen-able at various ratios. This may not be the definitive statement it claims to be. It's a marketing blurb intended for trade publications, to assure skittish theater owners that they should not hesitate to book widescreen pictures if they haven't yet changed over. The movie itself is undeniably widescreen, as can be seen in the special Columbia logo chosen (a taller platform for the Torch Lady) and the compositional shape of the main title text blocks. As for the superfluous 1:33 transfer (actually, 1.37:1 is the official flat Academy ratio), it is a precedent I'd like to see Criterion avoid. Several studios are already too cheap to remaster '50s widescreen movies properly, and this encourages them to keep doing so. I know more than one working restoration professional that can't be bothered about accurate ARs, so I can't imagine that the average home video executive gives a damn. 1 Of course On the Waterfront plays "all right" flat, even though the extra head- and foot-room defocuses dramatic scenes. Seen flat, the famous taxicab scene makes Terry and Charlie look as if they are riding around Manhattan in a funfair Tilt-a-Whirl car. I believe that Sony or Criterion has cheated the transfer in at least one instance. On old TV flat prints (back me up on this one, Randy) I have a strong memory of the scene where Friendly's hoods terrorize the meeting in Karl Malden's church. In the un-matted full frame, a big microphone boom loomed at the top of the frame so distractingly that I pointed it out to people on subsequent viewings. As I don't see the boom on the disc's 1:33 scan, I must conclude that the transfer artiste adjusted the scan to frame it out. Elia Kazan is of course one of the finest film directors of his time, and Criterion's many extras do no wrong by praising his personal achievement in On the Waterfront. Authors Jeff Young and Richard Schickel provide a laudatory audio commentary. Kent Jones and Martin Scorsese idolize Kazan in a nostalgic video featurette. Two long-form documentaries are included, one from 1982 on Kazan's career and a new item about the making of the film. Another piece addresses the taxicab scene. Eva Marie Saint appears in a new interview and Kazan himself in one from 2001. An actor recruited from the Hoboken neighborhood is interviewed, as is an author expert on the crime-soaked history of the New York docks. Finally, a visual essay on the Leonard Bernstein score is included as well.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

On the Waterfront Blu-ray rates:

Footnotes:

1. Hey, this particular movie looks mostly acceptable at any ratio, but now that we're finally in a widescreen video age, reproducing the correct AR shouldn't have to be a big problem. Some cable channels routinely trim 2:35 movie back to 1:78. Conversely, I would hope that home video policy will not be dictated by the annoying minority of online infants that like to attract attention to their own ignorance. We now have a vocal web columnist or two playing the same game. The new Hammer Company appears to be run by a similar breed of fanboy -- they adamantly proffer silly arguments to justify their wacko color and framing revisions to the Peter Cushing/Christopher Lee classics.

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with footnotes, reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||