|

|

|

|

Several years ago Criterion introduced us to director Keisuke Kinoshita through his gentle 1954 masterpiece Twenty-Four Eyes, a bittersweet memory of A schoolteacher's experience of World War II. That was after the MacArthur occupation, when Japanese filmmakers were no longer bound by strict U.S. Army censorship rules. Kinoshita's began directing right in the middle of the war with warmly expressive films about human values, despite the supervision of a military government that approved only those films deemed acceptably patriotic and optimistic about the war effort. Kinoshita fulfills those requirements yet frequently adds humanistic touches that soften or even contradict the official scripts. The fourth film included here went too far with its liberal values. The fifth is a postwar drama that takes an entirely different look at the war experience. Most if not all of these films have not screened much since they were new. They afford American viewers a unique opportunity -- as a representation of how our enemy saw itself and defined its values, Kinoshita and World War II has a few lessons to teach us about ourselves.

Port of Flowers (1943, Hana saku minato) is a charming and modest morale booster about a pair of comedic con-man that find their values changing when they encounter the residents of an island toward the South of Japan. The lightly satirical beginning shows three business locals congratulating each other on having locked up most of the island's commerce. All are fooled when a pair of bumbling crooks (Eitaro Ozawa & Ken Uehara) arrives, claiming to be sons of a speculator who tried and failed to build a shipyard fifteen years before. Kinoshita's trademark humanism shows through almost immediately. When the owner of the inn (Chieko Higashiyama) remembers a past love affair, the view outside her coach changes to reflect her memory. One of the swindlers falls in love with a local beauty (Mitsuko Mito) and reconsiders. A mystery woman related to the revered speculator arrives with a child in tow, but is obliged to keep her identity a secret. Then news arrives of the Pearl Harbor attack and initial victories, and everything changes. Building a ship is now a communal goal, and even the most conservative miser realizes that patriotism is more important than money. Instead of running away with their ill-gotten cash, the crooks have a change of heart. The show reinforces communal Japanese values. Even criminals reform when the country calls. Some of our equally propagandistic war morale movies used the same idea, as when gangster Humphrey Bogart turns Nazi-fighter in the comedy All Through the Night. Some interesting details slip through. Indonesia and China are mentioned as places now within the Japanese sphere of influence. The sneak attacks are celebrated as happy news: "We attacked Hawaii -- Banzai!" Specific mention is made of the surrender of the USS Wake, an incident that our side understandably did not publicize. A third-act crisis erupts when news comes that a U.S. submarine has sunk a local fishing boat. Kinoshita's emphasis is always on his characters. Each is afforded respectability, even a crotchety old man and a miserly fishing boat owner (Chishu Ryu). In his first film the director already has the makings of a stock company. Ken Uehara, Mitsuko Mito, Chishu Ryu and Eijiro Tono will return for his subsequent outings. 1

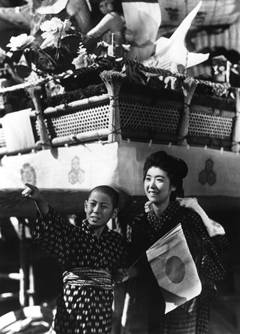

With The Living Magoroku (1943, Ikite iru Magoroku) Keisuke Kinoshita drops the comedy to fashion an idealistic image of the rural Japanese home front. The propaganda angles are obvious. Titled nobles and the servant class are encouraged to put their differences aside, a theme that correlates to William Wyler's Mrs. Miniver. The most honored tradition for these civilians turns out to be a reverence for military history -- as embodied by cherished Samurai swords. In Kinoshita's screenplay activists clash with the Onagi family over 93 acres of uncultivated land that could be planted for the war effort. The sacred site of the famous Battle of Mikatagahara, it hasn't been touched in almost 400 years. The young Onagi male heir (Yasumi Hara) has become a hypochondriac weakling. The domineering Onagi matriarch (Mitsuko Yoshikawa) refuses to break with tradition. Apparently the master-serf relationship also has survived, as Lady Onagi pointedly blocks the marriage of the main agitator to the daughter of her blacksmith. The local militia instructor (Ken Uehara) wants to instill the spirit of the samurai tradition in his (very young-looking) conscripts: dying in combat for the Emperor is a glorious ideal. An Army doctor (Toshio Hoskawa) tries to buy the militia leader's collector sword, only to find that it's a cheap fake. The plot is set in motion when he tries to buy a genuine museum-quality 'Magoroku' sword from the Onagis. The doctor inadvertently sold his own family sword, and seeks another heirloom to make amends with his father. In striving to regain his own pride, the doctor helps solve everyone's problems. It's not difficult to figure out the official messages that are being conveyed in The Living Magoroku. The landed noble class needs to put aside its entitlements and commit to the war effort. Womenfolk need to stop babying their sons and let the men make the decisions. Japanese honor is military honor. The drama ensures that the heir is cured, the land is cultivated and young love is set free; and every officer deserves a proper sword. The wise Onagi blacksmith (pictured ↑) forges a new sword for the cadet instructor to carry into combat: "Cut down 20 or 30 American weaklings, it won't even have a knick on the edge." 2 The acting is again excellent, with Toshio Hosokawa's doctor and Mitsuko Yoshikawa's Lady Onagi giving standout performances. Kinoshita stages an impressive opening prologue depicting the Mikatagahara victory of 1573. That ancient glory makes the Onagi's 'Magoroku' sword as sacred as the Emperor himself. The fake blade and the soldiers' bayonets can be shown on screen, but not the fancy heirloom of the Onagi clan.

The small-scale neighborhood drama Jubilation Street (1944, Kanko no machi) seems fashioned to mollify big city residents forced to relocate for the war effort. When a district is cleared out for Army use, several families must move. A successful businessman has decided to return to the country to become a farmer again. His wife thinks that she'll lose her social station and his daughter Takako (Mitsuko Mito) would rather stay near her local sweetheart, Shingo (Ken Uehara). He's considered a bad risk for a son-in-law: not only is Shingo's job as a test pilot too risky, his father abandoned the family ten years before. A bathhouse owner is in denial about the impending eviction while the operator of a tiny printing press has decided to donate the old but reliable machine to the war effort. As moving day approaches, other complications arise. Shingo tells no one that he'll soon be ferrying airplanes to a combat zone. His long-missing father (Eijiro Tono) suddenly returns. And Tanako's mother tries to force her to receive another, 'safer' suitor. With a less complicated story to tell, Keisuke Kinoshita concentrates on atmosphere and character detail. The camera direction is also more sensitive, especially when Kinoshita adds little camera moves to comment on characters and situations without dialogue. The director finds ways to make us like his characters. The bathhouse proprietor seems a miserable grouch until he pays a respectful visit to the printer, whose family is 'thanking' their old printing press with a prayer. The propaganda angles are less obvious in this show. Although the neighborhood has been seized by the state, no officials are seen telling people to leave or even looking around.. The good citizens accept their personal sacrifices and everything is voluntary. Jubilation Street premiered in June of 1944, well before the firebombing of Tokyo. The personal concerns depicted here seem trivial against the harsh fight for survival that would soon begin. The only event that hints at difficulties is probably just a coincidence: is the test pilot being sent to a combat zone because of a lack of manpower?

Released later in the same year, Army (Rikugun) is the series' clearest expression of the harsh military ideology imposed on the civilian population. Yet Kinoshita's humane touches frequently contradict the presumed intent of the dialogue script. Doing this would seem to be a risky endeavor... the military command can't have taken kindly to a civilian artist bucking the status quo. A prologue begins during a civil war in the 1800s, when an ancestor rescues a priceless set of military history books. Young Tomohiko Takagi (Chishu Ryu) reveres them and becomes a soldier in the Russo-Japanese war. While his comrade Nishina (Ken Uehara) is wounded multiple times and survives with a bad leg, various sicknesses prevent Takagi from fighting, which he takes as a personal humiliation. Unsuited to the family pawnshop business, Takagi opens a small store, lives more humbly and with his wife Waka (Kinuyo Tanaka) raises two boys. Buried in his military books, he becomes an expert on Japanese martial tradition and something of a super-patriot. This puts Takagi in good stead with factory owner Sakuragi (Eijiro Tono), who wants him to teach to a youth group he's organized. But Takagi's bullheaded manner keeps him unemployed and isolated. Waka supports her husband and is merciless when she detects cowardice in their oldest son Shintaro, who eventually joins the army, as does Sakuragi's son. Takagi, Nishina and Sakuragi eventually iron out their differences, as they're all "war buddies" united in the common cause. Army gives a good explanation for Japan's military mindset of the early 20th century. Tomohiko Takagi holds himself to a code of honor so rigid and exacting that he allows a petty point of etiquette to ruin his chances of a prestigious teaching job. He later quits the generous Sakuragi for good when the man dares to suggest that Japan could have been defeated in a war that took place hundreds of years ago. Takagi preaches Kamikaze -- the belief in a Divine Wind that will always intervene to bring victory. The script is packed with nationalist dogma that the Army propagandists clearly wanted presented without rebuttal. Takagi asserts that his country has the right to militarily strike out at any nation that (in the subtitle translation) "looks down on Japan". America and Britain are classified early on as aggressors 'meddling' in Japanese affairs in China. Takagi instills in his students the idea that their lives are already dedicated to one purpose. Waka states that she is merely borrowing her Shintaro, as all of Japan's sons belong to the Emperor. If or when war comes, she says she'll be proud to give him back. Takagi's only anxiety is that Shintaro may not die honorably. To us it all sounds like one big Death Cult. Army expects its audience to accept a very tough viewpoint. By comparison, Hollywood sought to reassure Americans that their husbands and sons in uniform were as secure as possible. The drama The Sullivans is about a famous case of five brothers lost on the same ship. The way the Navy's response is depicted, one would think it was a nurturing social service. Kinoshita's emotional approach adds question marks to many of Army's militarist statements. His beautiful, subversive final scene belongs solely to Kinuyo Tanaka's Waka, With her son leaving for war, she suddenly feels depressed. She stares at nothing for some time, with the soundtrack almost silent, but then hurries to join the crowds rushing to see the parade of departing soldiers. Waka finds Shintaro in the ranks of thousands of troops and runs alongside him, overcome by conflicting emotions. They smile at each other, but it's not a joyous moment in support of the film's militaristic text. Kinoshita's empathetic approach says something entirely different. When Army was released the volume of military death notices from Japan's war fronts must have been staggering. Eclipse's liner notes tell us that the film infuriated the authorities, who promptly cancelled Kinoshita's next project. The performances are excellent. Kinuyo Tanaka shines in the big finale but Chishu Ryu carries the picture as the harshly ethical Takagi. He, Ken Uehara and Eijoro Tono are in all four movies made during the war.

Morning for the Osone Family (1946, Osone-ke no ashita) should be a breath of fresh air in that it's Kinoshita's first film free of wartime supervision. But the edicts of the MacArthur occupation impose another strict set of limits. Port of Flowers was based on a play but this movie looks like one -- it all takes place in the household of the Osone family. We leave only for a brief dramatic finale. We're told that this coda was requested by the U.S. military, to leave the film on a more positive note. The story begins in 1943. Widow Fusako Osone (Haruko Sugimura) presides over a family formed by the liberalism of her dead husband. Her oldest son is arrested for writing subversive articles and the second falls into disfavor when he refuses to paint the portrait of a general. Daughter Yuko's marriage plans are blocked by her uncle, an Army Colonel. Her fiance is the son of an airplane manufacturer, and it would be bad form for him to marry the sister of a 'traitor'. As the Uncle is eager to have his kin die honorably, he urges the youngest Osone boy to enlist early: he claims that a few Army beatings will wean them away from art and literature. By 1945 the oldest son is still in prison and bombs are falling on Tokyo. The hated uncle moves in and makes things even worse. When defeat is near, his idea is for Japan to fight to the last man. Morning for the Osone Family is a beautifully directed drama yet plays like a test to clear Keisuke Kinoshita with the occupying American forces. Its insistent on pro-Democratic themes and speeches make this 'liberated' film more propagandistic than Kinoshita's wartime pictures. All attitudes and characters now illustrate the tragedy of militarism, with no shades of gray. The Osones are all anti-war intellectuals and artists, and the subversive writer is proved 100% correct. The only military representative on view is a hateful villain and selfish hoarder of foodstuffs. He isn't concerned that millions of his countrymen may starve to death, but worries that he'll be arrested as a war criminal. The ideological slant of this pro-Democracy film reminds me of East German propaganda, in which all the good Germans are of naturally oppressed communists that welcome the Russian liberators. Kinoshita stages the action and shapes the performances beautifully, as the loutish uncle and his meddling wife bring misery to their liberal kin. It's expertly done, but lacks the ambiguity and subtlety of the earlier films. The militarists in the wartime movies aren't caricatures and they state their obscene warrior philosophy right out in the open. Osone instead sidesteps touchy issues. No mention whatsoever is made of the dual atom strikes that ended the war. The only evidence of the American victors is one mention of General MacArthur. The U.S.- requested coda resembles something from a Soviet propaganda film -- the surviving players strike poses against a featureless background, point to a rising sun and proclaim happy times ahead. Like everything else by the talented Kinoshita, even the didactic scenes are brilliantly fashioned. The director enjoyed happy times of his own -- he reportedly received critical praise and popular acclaim throughout his career. Eclipse's DVD of Eclipse Series 41: Kinoshita and World War II is a select group of rarities. Considering when and by who they were made, it's fortunate that they weren't destroyed altogether. The films are intact but not in the best condition, and may be archival dupes or surviving collector's copies. The images frequently have light scratches and shrinkage, especially at the ends of reels. Although the audio can be hissy, the sound is acceptable. Filmgoers not already well versed on Japanese cinema will benefit highly from Michael Koresky's liner notes, which sum up the significance and qualities of each film in just a few paragraphs. The credits on the films are sparse. While using the liner notes to correlate character names with actors, I noticed that Koresky may have had the exact same problem. These exceptional films are blatant propaganda, yet also works of cinematic art. Koresky's notes steer clear of political interpretations, but that angle will be definitely be on the minds of most viewers. Access to foreign films on topics as contentious as war teaches us how fundamentally alike we are, even if our cultures are so different. What alarms me about the Kinoshita movies is their image of a country that officially embraces militarism as a defining principle. That wasn't the case with America in 1943 but it certainly seems to be the trend now.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor, Footnotes:

1. The names and faces are familiar from later classics by Ozu and fantasies from Toho. I don't know if this is really a Kinoshita stock company, or just the actors available to him at the Shochiku studio. 2. What did we expect? I imagine Japanese audiences of 1943 might respond to that line with cheers. Hollywood certainly showed Japanese soldiers gruesomely killed in our movies, while encourging hateful cheers and jeers. And the dialogue in more than a few American films encouraged audiences to regard the Japanese as subhuman vermin.

I'm not defending the Japanese, it just seems wrong to call these Japanese movies 'nasty war propaganda' without saying the same about many of our own.

The version of this review on the Savant main site has additional images, footnotes and credits information, and may be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||