| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

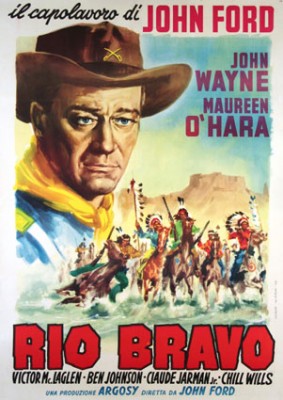

Rio Grande

John Ford hadn't actually planned to make all three of the pictures in what is now known as his "cavalry trilogy," but the director's circumstances (in the guise of Republic Pictures honcho Herbert Yates) circa 1950 dictated that he had to make another surefire-popular Western before Yates would give the go-ahead for the movie Ford really wanted to make, the riskier Technicolor non-Western The Quiet Man. So, with the intent of inspiring confidence and carrying his weight at Republic, Ford agreed to make one more in the very popular, John Wayne-starring vein of 1948's Fort Apache and 1949's She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, gathering together John Wayne and Maureen O'Hara, his designated The Quiet Man stars, for 1950's Rio Grande. Like its two successors, the film is based on a story by James Warner Bellah; unlike them, however, it was a film taken on more out of duty than love. The result, while it might seem a tad conventional and unfocused, hitting too many predictable marks modeled after/seeking to repeat prior successes, is anything but dutiful; Rio Grande might have been one he did for the studio, not himself, but Ford, his cast, and his crew don't skimp on the craft, skill, and passion for filmmaking.

A mustachioed Wayne is duty-bound Colonel Kirby Yorke of the U.S. Army Cavalry, formerly having fought on the Union side in the Civil War and now camped with his men on the U.S. side of the Rio Grande, defending Texan settlers from Indian tribes who have consolidated their power and are prone to making surprise attacks, then retreating back to the Mexican side of the river, where the Army is forbidden by international law to pursue them (to the very clear disapproval of the nevertheless obedient Col. Yorke). When we first meet Yorke, he's returning to camp from battle, his wounded and his captives in tow. This is the business of his life; news that happens to reach him about his son being kicked out of West Point for failing math might wounds the pride he has in his name, but it is really very remote, since Kirby apparently gave up being a family man to marry the Army a long time ago and hasn't even seen this disappointing son in 15 years. The tangled familial past he has left behind for a 24/7 career as a successful cavalry catches up with Kirby, however: Jeff, the late-teenaged, mathematically disinclined son (The Yearling's Claude Jarman, Jr.) he barely knows, has decided to enlist in the Army after his failed academic/military stint, and where should he be deployed but right to the little Texan camp where his stranger of a father will also be his commander?

Once it's made clear between them that no filial or paternal love will be lost if Kirby and son keep things on a strictly impersonal, honorable and professional soldier level (the two barely know each other, after all, though in a beautifully done little moment after the kid leaves his presence, Kirby Sr. measures his own height against his grown-up son's using a mark the very tall, straight-backed Jeff's head has left on the roof of his tent), we get to know some of the others in the too-small group of recruits (many fewer than the neglectful government promised, according to Col. Kirby) as they go about their preparations and routines. Sgt. Quincannon (Victor McLaglen), Kirby's colleague from the Civil War days and a drunken, crusty, tenderhearted old Irishman (a character who has only a good performance and some affectionate direction between it and being a rank stereotype) trains the group of newbies Jeff Kirby has made himself part of, prominent among whom is a hayseed called Daniel Boone, who, embarrassed once at not knowing "yo" is the proper response in cavalry roll call, makes it his answer to everything. These additional rings in Ford's circus make for extra color that broadens out the film's world, and some scenes of the men's camaraderie do seem vital and emotionally enriching (especially when they're singing, or learning to ride horses in a dangerous, thrilling "Roman" style). But they also lend a bit of an episodic, padded-out feel at times; the jokes are corny, eventually losing their charm, and the quirkiness begins to seem extraneous, sometimes giving us an interesting (and, without fail, enthusiastically and beautifully shot/edited/performed) picture of life in the cavalry, but at others feeling like a delay tactic, foot-dragging to avoid cutting too quickly to what's principally at stake.

What that is comes into sharper focus with the arrival of Col. Kirby's estranged wife, Kathleen (O'Hara), who's out to buy her son's way out of the Army that came between her and her husband (in a backstory that slowly, richly emerges, the Civil War had put husband and wife on opposing sides, placing her family's plantation directly in the scorched-earth path of Kirby's and the "arsonist" Sgt. Quincannon's path, for a history littered with layers of divided loyalty, tension, disappointment, and resentment). But there's still a spark there; the nighttime scenes, candle or lamp-lit inside barracks and tents, between Kathleen and Kirby, and between Kathleen and Jeff, are full of unspoken emotion, tension, conflict -- fathomless layers of feeling that Ford lets the lighting, framing, and performances, much more than any dialogue, convey. (Adding some indispensable aural and pictorial texture to the first unexpectedly romantic husband-wife dinner is the arrival of serenading regimental singers, played by folksinging group Sons of the Pioneers, who stop the film in its narrative tracks for entirely justified reason, taking up and running with the thread of music, also including Victor Young's melodic score, that weaves itself most pleasurably in and out as the story unfolds.) Ford's more famous talent, for the kind of rough-riding and action a cavalry is bound to find itself in for, is also on full display here, with the horseback shootouts and war-like situation between the cavalry and their Indian opponents eventually overlapping with the domestic drama of the Kirbys, bringing it to a head as innocent (women, children) settlers are kidnapped and carried by the consolidated enemy tribes to the Mexican town across the Rio Grande. Kirby is finally given permission to pursue them; with the children in jeopardy, even pacifistic Kathleen can't begrudge her husband his vocation, or her son (now joined with his father, ready to acquit himself honorably on the mission) his need to follow in those deep, forbidding, perhaps ill-advised footsteps. Whether the ending represents an impasse or a resolution is up to you, but it's weighted with enough restraint, realism, and melancholy not to feel glib, unearned, or simplistic in any way -- a conclusion with some apparently likely happiness mixed in, but not quite a "happy ending."

It's hard to say exactly where the peripheral elements/characters of Rio Grande stop adding a far-ranging sense of fullness to the film's depiction of Army life and start becoming a bit of a less-amusing-than-intended bore, but it should (and could) probably have been a leaner, more powerful film, with more (but not all) of the teeming, episodic life of the regiment left on the cutting room floor in favor of a focus on the more interesting and weighty matters at hand. Still, there's not a scene that isn't well-crafted, well-played, and skillfully shot (by painter of light Bert Glennon, who also did Stagecoach and Young Mr. Lincoln for Ford) and edited; nobody could ever fault Ford or anyone else involved with phoning in their creative work here just because the film is by definition less of a personal project for the auteur than his best work. The exteriors are, of course, gorgeous (some may find Ford's Americana jingoistic, and there is obviously much to be felt out, discussed, and interpreted when it comes to his films' take on problematic U.S. history, but when you see the eerie, strange, awesome beauty of the Southwestern landscape in which his characters' dramas and inner conflicts play out, it becomes much more complex than that), but Ford's visual sense on the whole is something special, including the less showy but no less impressive smaller-scale feats he's capable of. His placement of characters (often at different points in the deep-focus space and/or positioned as opposites, as if in an unknowing face-off) and the chiaroscuro variegations of light, dark, and speckled shadow within the frame in "smaller" scenes (the patterns of branches and leaves, projected from sunlight above, visible from the inside on tent ceilings, or the candles' glow bathing Kirby and Kathleen and heightening the surrounding shadows as they sup) are, in their way, as breathtaking as the sweeping, spacious vistas; whatever else it is or isn't, the film is unequivocally a nonstop feast for the eyes and ears. Given these qualities, and despite its being a bit too overstuffed and diffuse to attain real excellence, it's hard to complain too much, because every moment of Rio Grande contains some visual, performative, narrative/dramatic, musical, or other cinematic pleasure in it to reward our attention. The hallmarks of Ford's filmmaking are its aliveness, its palpable craftsman's pleasure in the storytelling possibilities opened up when making a movie (so much can be said with image, sound, montage; so little has to be conveyed verbally), and Rio Grande is brimming over with the intense, passionate, unmistakable sort of creativity that signifies you're in the hands of one of the great American filmmakers. Imperfect as it sometimes is, is never for a moment anything less than drunk on the infectious, giddy love and joy of making movies.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

Presenting the film at its original 1.37:1 theatrical aspect ratio, the picture quality on this Blu-ray edition is very high; some flicker that seems due to print wear is noticeable at certain points, as is a tiny bit of edge enhancement, but these are both extremely minor. For the most part, the rich black and white contrasts of 's cinematography is fully intact (the solidity and clarity of dimmer nighttime scenes is especially impressive), as is the celluloid texture (no overuse, if any, of digital noise reduction). A very pleasing job overall.

Sound:The DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 soundtrack gives us the film's original monaural sound in very good shape; there was only one fairly brief instance of what sounded like background hiss/crackle, with the sound otherwise clear, sharp, and undistorted throughout.

Extras:"The Making of Rio Grande," a 22-minute TV special hosted by Leonard Maltin, in which the critic explains how the film came to be and contextualizes its making in the context of Ford's career. Anecdotal interviews with John Wayne's son Michael and co-stars Harry Carey, Jr., and Ben Johnson are fascinating, most especially in the little details (unsurprising if you know anything about Ford, but still) about the director. (Note: The pop-up menu claims you're selecting "The Making of High Noon," which is understandable, given that Olive's release of High Noon contains a Maltin-hosted making-of from what looks to be the same series, but never fear: the content is correct.)

The film's theatrical trailer, which, beyond just offering an enjoyably hyperbolic example of what trailers tended to be like then, also demonstrates just how much better the scenes included look on the main feature's transfer.

Ultimately one of master John Ford's more minor works (and probably the least of the "cavalry trilogy" it brings to a close), Rio Grande is nevertheless a feast for the eyes and the mind, an expansive Western containing all kinds of golden cinematic nuggets just waiting to be gleaned. Though the film's central cavalry-commander protagonist is a hero of more the unexpectedly vulnerable than the flat-out "anti" variety, John Wayne's persona here is in transition, evolving toward the complexity he would have to embody for Ford as Ethan Edwards in The Searchers a few years later (the top career peak for both). Wayne and Maureen O'Hara (whose characters' family, broken apart by the ongoing divisions and resentments of the Civil War and badly in need of repair, is the axis around which Rio Grande's various strata of cavalry life, action, music, and melancholy revolve) have real chemistry, striking at something deep as an estranged married couple whose struggle with each other over their son and all their contradictory feelings seem to find their natural, heightened setting against a backdrop of jeopardy (the threat of Native American attacks makes for plenty of excellently shot, roiling cowboys 'n Indians action) and Ford's magnificent Western/desert landscapes. It's not one of the biggest standouts in Ford's career -- not at all on par with Stagecoach or Young Mr. Lincoln or The Searchers, because noticeably more conventional and less ambitious -- but it makes for a wonderful appetizer or palate cleanser, something one doesn't want to overlook when digging into the feast that is Ford's filmography. His name was John Ford and he made Westerns, according to the director's own famously terse self-description, and in the case of a Western as recognizably Fordian -- as intensely made, engaging, and able to switch adeptly between all gears, from the purely physical to the most delicate and understated emotion -- as Rio Grande, that's all you really need to know. Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||