| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

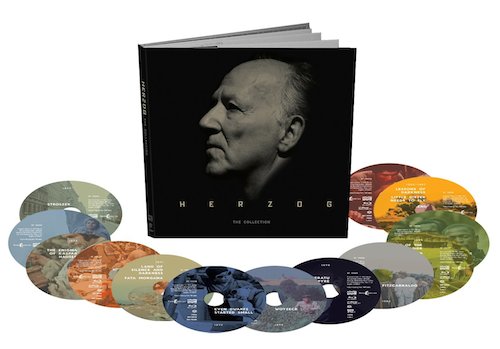

Herzog: The Collection

There is no filmmaker quite like Werner Herzog. His idiosyncratic, Bavarian sensibility manifests itself in films that can be ridiculous, gorgeous, surreal, and naturalistic, often all at the same time. The 16 films featured in Shout! Factory's new 13-disc Blu-ray box set are essentially the filmmaker's best known films from 1970 until 1999, including his five films with actor Klaus Kinski. This timeline means we don't get any of his recent acclaimed documentaries or his wildly eclectic recent features, but there is more than enough to treasure here. And hey, we can hope for Volume 2 (and 3, and 4...).

There's plenty to say about each film, so I'm just going to dive in. Here we go, in box set order...

Even Dwarfs Started Small

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras:

Extras:

Herzog: The Collection has been organized in mostly chronological order, which is logical, I suppose. Nonetheless, it feels sort of off to begin this box set with 1970's Even Dwarfs Started Small. Dwarfs is excellent, but it is such an oddity -- like Tod Browning's Freaks crossed with Dušan Makavejev's Sweet Movie -- that new viewers might be scared away, thinking everything else in the box is similarly crazy. Don't get me wrong: Herzog's sensibilities are nowhere near the middle of the road, but Dwarfs is the only one of his "classic era" films that could be mistaken for a cult-y midnight movie (the more recent Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans might qualify too, if only for the crazy-Cage factor). When outsider filmmakers like Crispin Glover, Harmony Korine, and Giuseppe Andrews say that they are inspired by Herzog, this seems like the film that must have rubbed off on them the most.

Cast entirely with non-actor little people, Dwarfs portrays the aftermath of a rebellion at a secluded institution. For protection, the man in charge of the asylum, referred to as "The Instructor," has taken an inmate hostage in his office. The rest wander around the grounds, reveling in their freedom -- which is to say, creating chaos and acting on their most primitive impulses. They dump gasoline on flower pots and light them on fire. They start an impromptu cockfight. They hot wire a truck, but rather than escape with it, the characters just set it up to perpetually do donuts in the courtyard. Herzog has resisted most attempts to interpret the film, although clearly he has a bleak view of human nature and a skepticism of how humans behave when they're "free." If the characters' behavior didn't make this clear enough, Herzog shows the unsavory doings of animals living on the institution's grounds -- chickens fighting over a dead mouse, piglets suckling on a dying sow -- as if to say, "Animals have no morality, why would we?"

The film's most memorable images -- a mock-religious processional led by a monkey tied to a crucifix, a character laughing himself sick while looking at a very confused camel -- have a distinct WTF!? quality to them, but Dwarfs is not just a shocking novelty. Herzog is clearly fond of his small stars, and that makes their nihilistic actions attractive while being repulsive. Dwarfs may not strive for the thematic depth of many of Herzog's later films, but the power of its strange images is not to be underestimated. During this re-watch, I found myself completely hypnotized by Herzog's viscerally immediate, uncannily surreal nightmare.

On the technical side, the 1080p AVC-encoded 1.33:1 video image was incredibly sharp and clean, with pleasing film grain, inky blacks, and good contrast overall. Only occasional issues with digital noise detracted from the presentation. The German DTS-HD MA 2.0 mono audio (with optional English subtitles) is a little crispy on the high end but otherwise quite strong with no significant damage, hisses, pops, etc.

The only bonus feature is the Audio commentary by Werner Herzog, with moderator Norman Hill and filmmaker Crispin Glover, which is ported over from the Anchor Bay DVD. The commentary is fascinating, immediately engrossing, and maintains interest throughout the film. Some good anecdotes involve Herzog's long-time film editor who hates most of his movies but liked this one, Herzog's infamous jump into a cactus as a kind of thank-you to his actors for doing dangerous actions on-camera, and Herzog's own habit of running cars in circles out of boredom when he worked at a parking lot as a youngster.

Land of Silence and Darkness

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras: N/A

Extras: N/A

The first documentary in the set, from 1971, is an astonishing film. 56-year-old Fini Straubinger had been deaf and blind for around forty years when Herzog filmed her. She had spent thirty of those years isolated in bed before gaining a new lease on life through learning a kind of tactile sign language that involves tapping and rubbing parts of the person's hand to spell out words. Now she and many other deaf-blind people like her -- with the help of interpreters -- are able to socialize, have experiences in the world, and gain a little nourishment for their minds that, in many cases, had been lacking for decades. Herzog captures Fini's birthday party, which includes a trip to a botanical garden to feel different cacti.

Unlike in many of his later documentaries, Herzog does not put himself in the film; although there is narration, it is spoken by an actor and does not have Herzog's signature deadpan flavor. Nonetheless, Herzog's unique curiosity make this film mesmerizing, especially in the later sections where Fini travels to different parts of Germany to visit people who have the same affliction -- "the land of silence and darkness," she calls it offhandedly, naming the film unintentionally. She meets many people who have become deaf and blind through circumstances frequently more desperate than her own. There is a middle-aged woman named Elsa who is in a mental asylum because her mother died, leaving no one else around who could understand her. Fini tries to talk to Elsa and raise her spirits, but Elsa is so withdrawn that she makes no sign of comprehending anything that Fini does. Surrounded by bored-looking women from the asylum, the failed conversation is heartbreaking.

Fini also visits children who have been deaf-blind since birth. Two young brothers are shown getting vocabulary lessons, touching the teacher's jaw and attempting to reproduce the sounds. It's fascinating to watch the process, to see that they can find a way to communicate and gain an understanding of a world they cannot see or hear. Fini also visits a 22-year-old man named Vladimir who was never given lessons when he was younger and is almost a lost cause in that respect. He cannot walk or eat hard food - he is shown taking immense pleasure in scarfing down a banana and looks astounded by the vibrations of a radio.

Land of Silence and Darkness does not serve a broad message about the plight of the deaf-blind although, after watching it, one could certainly be inspired to donate to the organizations which help them to learn to communicate. One is left with an overall feeling of empathy which helps the film resonate long after it is over.

On the technical side, the AVC-encoded 1080p 1.33:1 image is good, considering its 16mm documentary origins. The print reveals some dirt and other specks, but they are not excessively intrusive. Most of the film has solid clarity, with a few noticeably soft sections due to the impromptu nature of the filming. I saw no dramatic compression issues with this film. The DTS-HD MA German 2.0 audio (with optional English subtitles) sometimes sounds a little distorted during certain moments of field-recorded dialogue, but overall it has good fidelity.

Fata Morgana

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras:

Extras:

1971's Fata Morgana was originally conceived as a science-fiction film, where fictional narration would be juxtaposed with documentary footage of the Sahara in Africa. Although Herzog would eventually realize his vision of a documentary/sci-fi hybrid, to differing degrees, with 1992's Lessons of Darkness (see below) and 2005's The Wild Blue Yonder, he decided to just let this Saharan footage essentially speak for itself. The end product feels like a less didactic variation of Godfrey Reggio's later Qatsi Trilogy, with images of untouched desert juxtaposed with shots of man-made objects in the desert, like warehouses and barbed wire fences.

The first of the film's three sections features narration read by film critic Lotte Eisner, taken from the Mayan creation myth, Popol Vuh (which also inspired the name of the music group that frequently scores Herzog's films). It is the most earnest portion of the film, embodying an exploratory curiosity of this secluded area. As the film progresses, through sections with the titles "Paradise" and "The Golden Age," Herzog focuses more and more on the ridiculousness of the civilization man has created in the midst of the natural world. The final section seems particularly bitter, with Herzog returning again and again to an odd South American male-female piano and drums musical duo passionlessly running through kitschy songs highlighted by unintelligible vocals. Unlike almost all of the selections in this box set, the various elements of this film -- dreamy photography, esoteric narration, and an unusual mix of music cues -- don't really coalesce into something much greater the sum of its parts. Moments stand out as eye-catching, and the film's use of early Leonard Cohen songs is particularly evocative, but, as a whole, Fata Morgana is inessential Herzog.

On the technical side, the AVC-encoded 1080p 1.33:1 video isn't perfect, but like many of the films in this set, the shooting conditions are at least partially to blame. The film image often has a grainy, impromptu quality, and I noticed a little bleeding at the edges and video noise in some instances where there was a stark contrast between bright and dark, like in wide shots of the desert, with bright sky and darker earth beneath. Otherwise, the clarity is solid and the colors are strongly saturated. There are two audio tracks. The German DTS-HD MA 2.0 audio (with optional English subtitles) sounds clean and clear, if not very dynamic. The Leonard Cohen cues, for example, seem a little bit quieter than you might expect, although this very well could be a stylistic choice -- as though the songs are in the back of our minds as we see the images, not intruding on the visuals. The English DTS-HD MA 2.0 audio track is a little quieter than the German, and, as seems to be Herzog's preference when dealing with foreign languages, consists of English translators speaking over the German dialogue. (An optional English subtitle track that fits with the timing of the English speakers is also provided.)

Once again, the sole bonus feature from the Anchor Bay DVD, an Audio commentary by Werner Herzog, with moderator Norman Hill and filmmaker Crispin Glover, has been ported over. Herzog again has plenty of good anecdotes, such as the reveal that the odd piano and drums duo was actually a madam and a pimp who would lifelessly perform as they do in the film for their customers. He also mentions his month-long walk to see Lotte Eisner -- supposedly to keep her from dying -- that he also documented in the book Of Walking In Ice.

Aguirre, The Wrath of God

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras:

Extras:

Aguirre, from 1972, is the first of Herzog's five films made with star Klaus Kinski. Theirs is a working relationship that stands with Mifune-Kurosawa and De Niro-Scorsese as being amongst the most fruitful collaborations between actor and director. The film introduces many elements that would recur throughout their films, including a story about a madly ambitious loner, a South American setting, and, most amusingly, a tendency to cast the blond-haired, blue-eyed, thickly accented Kinski as characters whose ethnicity is not German.

In this case, Kinski is the real-life explorer Lope de Aguirre, who was part of an expedition that started in Peru, in search of the legendary city of El Dorado. The man in charge, Pizarro, sends three rafts down the Amazon on a scouting mission, with Aguirre as second-in-command. A variety of misfortunes befall the three rafts, including encounters with rapids, attacks from natives, and Aguirre's own treachery. Though Kinski says relatively little for the first two-thirds of the film, his expressive face makes it clear that his character is pulling strings to gain power without blatantly seizing control of the expedition. Eventually, Aguirre (and, I'm sure, Kinski) is no longer satisfied to be plotting from the sidelines, and he takes charge over the ever-dwindling crew. This development turns out to be bitter comedy (a Herzog specialty), of course, since the mission was doomed from the start. Who cares if you're the man in charge, if there's only fool's gold in them thar hills?

As with many of his films, Herzog's elliptical approach to storytelling, punctuated by shots of the impassive landscape, gives Aguirre a hypnotic quality which elevates its simple plot to a metaphysical level and turns Aguirre from a base villain into a mythical tragic figure.

On the technical side, the AVC-encoded 1080p 1.33:1 image is typically very sharp, with nicely saturated colors, and -- apart from the credits sequence - it is free from film damage. Some of the shots are soft, but this seems likely the result of the less-than-ideal shooting conditions. There are three audio options, a German DTS-HD MA 5.1 remix that is extremely atmospheric and immersive, and plays much more subtly than the other mixes. Oddly, the musical cues by Popol Vuh seem to be pitched lower than the other two mixes - is this a mistake or a correction? The original German DTS-HD MA 2.0 mix features dialogue and effects with much more presence, making it blunter than the 5.1 remix, but it might nonetheless be more satisfying for viewers who remember the original release. The English DTS-HD MA 2.0 mix is even louder than the German 2.0. The mouths match better on this dubbed track, which leads me to assume most of the actors said their lines in English and were dubbed into both German and English later for practical reasons. Even though the sync is better, I still prefer the German performances. Both the German and English tracks come with optional English subtitles to fit the timing of each version.

This time, there are two audio commentaries, one ported over from the Anchor Bay DVD, with Herzog and Norman Hill, and one ported over from the German DVD release from Arthaus, with Herzog talking with his long-time distributor Laurens Straub in German with optional English subtitles. As with all the titles that have both English and German commentaries, there tends to be a lot of overlap in regards to production anecdotes, although the German commentary typically has a slightly more intimate tone. The disc also features a Theatrical Trailer and a Still Gallery (HD, 5:15).

The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras:

Extras:

Next to Kinski, Herzog's most compelling leading man was Bruno S. A street musician who had spent his life in and out of institutions, Bruno has a unique air of combined naivete and world-weariness. After seeing him in a documentary on street performers, Herzog knew he had to cast Bruno in his 1974 fact-based drama about Kaspar Hauser, a young boy who was discovered in 1828, abandoned in a city square without the ability to speak and relate to other people. Once he was taught language, Hauser explained that he had been kept hidden away in a barn for as long as he could remember by an unknown captor. While Hauser was actually a teen in real life, a few decades younger than our star, Bruno's unique attitudes and behavior make it impossible to imagine anyone else in the role.

It's also hard not to draw parallels between Bruno's life and what happens to Kaspar in the film. An outcast from the society which claims it wants to help him, Kaspar is made to appear in sideshows to help pay for his expenses. Eventually, Kaspar is adopted by a foppish English aristocrat, who shows his new ward off like a pet at parties... until Kaspar bristles at his treatment and becomes tiresome to his benefactor.

The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (whose superior German title translates as Every Man For Himself and God Against All) is one of Herzog's most emotionally affecting films, and it is largely because of his one-of-a-kind star. Whether describing the intelligence of an apple that chooses to jump over a man's foot rather than be stopped by it or relaying Kaspar's existential crisis through lines like "Why can't I play the piano like I can breathe?," there's a guilelessness to Bruno's performance that seizes moments that could be potentially maudlin on paper and reveals the painful truth in them.

On the technical side, the AVC-encoded 1080p 1.77:1 video transfer boasts excellent clarity. The colors are a little muted, but it seems to be a stylistic choice. Apart from one sequence that seems to be poorly utilizing the day-for-night effects, the contrast is also excellent. No crushing in the blacks, no burning out in the whites. There's no film damage, either, apart from the dream sequences shot on 8mm film that have some dirt and specks, which gives them a home movies feel. I noticed no major compression issues. The German DTS-HD MA 2.0 audio (with optional English subtitles is clean and clear, but not very expansive. This is suitable, though, for this fairly intimate story.

Bonuswise, we are again treated to another excellent Audio commentary by Werner Herzog with Norman Hill that provides interesting background both on the historical figure Kaspar Hauser and on Herzog's experience working with the inexperienced, often distrustful Bruno S.

Heart of Glass

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras:

Extras:

The term "hypnotic" can be used to describe many of the films included in this set, but 1976's Heart of Glass is the only one where Herzog pondered creating a prologue where he would personally hypnotize the audience and then provide an epilogue where he would take them out of the trance. Understanding the impracticality of this, as well as the potential danger, Herzog set that idea aside. Even without such blatant methods, Heart of Glass has an entrancing, somnambulant rhythm that can provide viewers with the sensation of being in a trance. Part of this effect was achieved by hypnotizing almost all of the cast for most of their scenes (since some of them are called upon to blow glass, these craftsmen were taken out of their trances for these moments).

The film takes place in a small Bavarian village known for its glass blowers and their signature red "Ruby glass." When the only man who knows how to make the glass turn red dies, a pall falls over the village. The glass factory owner (Stefan Güttler) becomes obsessed with finding documentation of the missing ingredient, which leads to drastic measures, such as calling on a clairvoyant cowherd named Hias (Josef Bierbichler, the only actor who is never hypnotized) to reveal it. The town acts out violently, too; although under hypnosis, it becomes a kind of slow-motion slapstick. One notable scene has a fight break out between two friends in a bar. One friend breaks a mug of beer over the other's head. Breath, breath, breath. Then, finally, the injured man retaliates by pouring beer over the aggressor's head.

Heart of Glass tells a simple story about the downfall of this village and its maniacal employer, but Herzog's particular mixture of lyricism, stylistic alienation, and morbid humor makes Heart of Glass an ambitious standout in a career full of them. The film might not achieve all of its aims, but it is no less fascinating for the effort.

On the technical side, the AVC-encoded 1080p 1.66:1 video is typically quite pleasing. Like Kaspar Hauser, this film has an 8mm dream sequence that has some dirt, but otherwise the image is clean and stable. A few stray shots have slightly milky blacks and/or wrong-looking skin tones, but these moments are pretty limited. The German DTS-HD MA 2.0 audio (with optional English subtitles) is clean and clear, although there doesn't seem to have been a lot of sweeetening of the dialogue, so some of the scenes set in small rooms sound a bit dull. Popol Vuh's prog rock score and a handful of more traditional music cues all sound lively.

Bonus-wise, there's another Audio commentary by Werner Herzog with Norman Hill. It is an excellent, completely engaging talk, in which Herzog discusses the distinctly Bavarian nature of the story, the hypnosis process, his conceptual ideas for the film, and plenty of production tidbits.

Stroszek

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras:

Extras:

Herzog initially intended to reteam with his Enigma of Kaspar Hauser star Bruno S. for a film of Georg Büchner's play Woyzeck, but eventually realized during preparation that it was a role better suited for Klaus Kinski. As a kind of apology, Herzog created a different vehicle for Bruno that pulled many of its details from real life. Like the actor playing him, Bruno Stroszek has spent a life in and out of institutions. When we first see him, Stroszek is getting released from prison after a stretch of two and a half years. He returns to normal life in Berlin, but finds that trouble refuses to leave him alone. When he offers to let a down-on-her-luck prostitute named Eva (Eva Mattes) stay with him, this angers the low-life gangsters who have been acting as her pimps. They beat up Eva and Bruno, and wreck his apartment. Working as a street musician doesn't offer much income, and Berlin seems less friendly by the minute, so this unlikely pair decides to go with Bruno's neighbor Scheitz (Clemens Scheitz) to live in Wisconsin, where Scheitz's nephew lives. Though there are some comic fish-out-of-water moments, such as Bruno wearing a cowboy hat and Eva luxuriating in their new massive mobile home, the film is essentially tragic and this move to America doesn't solve any of the characters' problems. It just amplifies them in a different way. Before long, the bank is threatening to repossess their home for non-payment and Eva returns to hooking, partly for the money and partly to alleviate the boredom of becoming a truck stop waitress in Wisconsin.

Some writers have characterized Stroszek as some kind of anti-American screed, but it really just uses the alienation of the foreign Wisconsin landscape to underline the no-win situation of its main characters. Herzog famously illustrates his theme in two indelible scenes: one involving a premature baby and one involving a dancing chicken. A doctor shows Bruno the tiny preemie and illustrates its instinct to latch onto the doctor's fingers and never let go. "Perhaps this baby will become chancellor one day," the doctor says, showing the kind of determination needed to make it through the worst circumstances, a determination that Bruno lacks, probably because the system has already beaten it out of him. As Bruno explains to Eva when she says no one is kicking him in America: it doesn't have to be visible, and it's usually worse when it's mental. That seems be the thinking behind the image of the dancing chicken, which appears near the end of the film when Bruno is at the end of his rope. He wanders through some kind of tourist rest stop and puts money into a bunch of coin-operated animal attractions, which include a bunny that triggers the siren on a fire engine, a chicken that pecks a piano, and a chicken that dances. These animals are all presumably trained to do these unnnatural tasks for some kind of reward, performing silly actions every time someone puts in money.

That metaphor is pretty clear in connection to the plight of Bruno Stroszek, but the film isn't memorable for being an activist piece of anti-capitalism. Herzog's empathetic treatment of his characters and appreciation of their uniqueness makes the film immersive and eventually heartbreaking. When Bruno leaves his cellmates behind at the beginning of the film, he says, "You can have my television," referring to a hanging water bottle that reflects the happenings on the street outside. It's these kind of details which gives the film its unmistakable flavor and shows that, while Herzog's fiction filmography is mostly made up of period pieces, he has a wonderful eye for portraying modern Berlin that echoes contemporaries like Wim Wenders and Rainer Werner Fassbinder but is idiosyncratic and completely distinct from their work of this era. Though it's not frequently spoken about as Herzog's best work, Stroszek nonetheless might be my favorite of Herzog's films.

On the technical side, the AVC-encoded 1080p 1.66:1 transfer offers typical damage-free images, with excellent clarity, and minimal compression artifacts. The cinematography by Herzog's frequent shooter Thomas Mauch features a lot of whites and beiges and browns in Germany, and a more colorful palette in Wisconsin. The American section of the film has a naturalistic look that highlights the wintry landscape and wide open spaces that, despite their difference in geography, feel reminiscent of Wim Wenders's Paris, Texas. The German DTS-HD MA 2.0 audio (with optional English subtitles) has a good dynamic range overall, but can a little hissy on the S's and has a distinct crackle during some later dialogue-free scenes.

Again, the bonus material consists of Audio commentary by Werner Herzog with Norman Hill Herzog repeats some of the info from the Kaspar Hauser commentary about meeting Bruno and writing this vehicle for him, after deciding he wasn't suited for Woyzeck. Herzog and Hill continue to have a good rapport, discussing the production and the ongoing development of the ideas for the film. A trailer is also included on the disc.

Woyzeck

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras:

Extras:

1979's Woyzeck is Herzog's third collaboration with Klaus Kinski (although it is oddly included before the second one, Nosferatu, in this collection). The film is a bit atypical for Herzog, who adapts an unfinished play by Georg Büchner and gives much of the film a play-like atmosphere, using long takes with minimal movement during many talky scenes. Cinematographer Jörg Schmidt-Reitwein's spotlight-heavy lighting schemes, which are incredibly evocative in Heart of Glass and Nosferatu, feel particularly theatrical in this iteration.

Kinski's acting is atypical here too, as he plays a soldier undergoing psychological experiments that eventually drive him to murder his wife. Though Kinski often displays a kind of madness in his performances, his Woyzeck is something different: not a powerful man, just a supplicating weakling full of pain and anger. Woyzeck is pushed around by his superiors, but when he snaps, he does not fight against the men who tinkered with his mind, he kills unfaithful Marie (Stroszek's Eva Mattes), because she is the straw that breaks the all-too-fragile camel's back. Both Kinski and Mattes are powerful in their roles, which undeniably makes Woyzeck engrossing to watch. However, the distastefulness of the story and the alienating aspects of the film's theatricality make this the least of Herzog and Kinski's collaborations.

There has already been some uproar online about this AVC-encoded 1080p 1.66:1 transfer, based on some screenshots demonstrating terrible film-grain reproduction and excessive digital noise. And, it's undeniable, the murder scene looks bizarre -- in what seems to be a perfect storm of unattractive photochemical processing and excessive digital scrubbing. Potential consumers should breathe easier though, because the rest of the film is not nearly so heinous, apart from a few instances of digital noise. Mostly, there's pleasing film grain, good detail, and excellent color reproduction. The German DTS-HD MA 2.0 audio (with optional English subtitles) is pretty typical for this collection, with interior scenes sounding a little on the flat side, when the dialogue hasn't been dubbed over.

For bonuses, we return to material from the German Arthaus DVD and a Conversation between Herzog and Straub (HD, 58:56), which is an audio-only feature in German (with a still photo and burned-in English subtitles) that basically takes the place of a commentary. The talk covers topics such as the Buchner source material, the German-ness of the film, and practical information about the film production. It's a little harder to concentrate upon than a typical commentary. German speakers might want to rip the audio and treat it like a podcast, but it might be tougher going for English speakers. Also included is Portrait: Werner Herzog (HD upconverted from SD, 29:48), an autobiographical profile of Herzog from 1986, presumably intended for for German TV. Predictably, it is mostly in German with burned-in English subtitles. The featurette seems to be an attempt to portray what Herzog does between projects, which includes hanging out at a beer tent, discussing pre-production on a film set in the Himalayas (which never came into being), and talking with mentor Lotte Eisner. A number of clips from his films up to this point are excerpted, including a handful that aren't even in this set. A stills gallery is also featured.

Nosferatu the Vampyre (Nosferatu: Phantom Der Nacht)

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras:

Extras:

Herzog attempts a genre picture, by remaking F.W. Murnau's classic silent film Nosferatu, which itself was an adaptation of Bram Stoker's Dracula, but with the names and certain details fudged to avoid copyright infringement. Herzog has brought back the original names of the characters (mostly), but his film won't be mistaken for Bram Stoker's Dracula any time soon. The aesthetic is distinctly Murnau's, as filtered through Herzog. Klaus Kinski stars as Dracula, and he is no dapper gentleman. With a smooth bald head, garish large ears, and a colorless complexion, Kinski's Dracula resembles a pathetic snake, particularly when he bears his fangs. As in the original story, Jonathan Harker (Bruno Ganz) goes to Transylvania to discuss business matters with Count Dracula, but ends up a prisoner of the blood-sucking count. Back at home, his beautiful wife Lucy (Isabelle Adjani) fears for his safety when she should fear for her own, because Count Dracula has seen her picture in her husband's locket, and he is coming for her.

Herzog's Nosferatu lacks the jump-scares and onscreen violence modern viewers tend to expect from horror movies. Instead, Nosferatu is deliberately paced and creepy as hell. The film insinuates itself into your very being. Kinski's performance is perfectly modulated, showing Dracula to be equally pathetic and powerful. Ganz and Adjani both play well with Kinski, sometimes going over the top so that he can remain threateningly understated. Herzog throws in some darkly comic moments -- like a great left-field scene at the end with Stroszek's Clemens Scheitz -- but mostly he maintains a brooding, unsettling aura that makes this one of the all-time great films, right up there with its inspiration.

This disc appears to be essentially the same one that was released back in May by Shout! Factory. It includes both the German-language version of the film and the English version shot at the same time. As is already well-documented, the AVC-encoded 1080p 1.85:1 video on both of these is fairly problematic, with certain shots overwhelmed by digital noise, moments when the detail is completely obiterated in the blacks, and even a scene where the mixture of optical duping and digital scrubbing makes the image look like a watercolor painting. This does not occur constantly -- thank goodness -- but it is striking enough when it does occur to distract attentive viewers. Otherwise, the film typically looks pretty good with low-key, high-contrast lighting that actually hides a lot of these digital hiccups and accurate looking colors. The German version of the film comes with German DTS-HD MA 5.1 surround and German DTS-HD MA 2.0 stereo audio mixes (both with optional English subtitles), and, unlike with Aguirre, I feel that the original 2.0 mix wins hands down. Where the 5.1 mix gave Aguirre a more immersive atmosphere, for Nosferatu a seemingly similar approach actually diminishes the original sound work. The English version of the film only comes with an English DTS-HD MA 2.0 audio mix (plus optional English subtitles), which is fine. (Though it is interesting to compare the many slight differences between the German and English versions, I find the German to be preferable overall.)

Again, we are treated to two audio commentaries for the German version. As before, one is in English with Herzog talking to Norman Hill, and the other is in subtitled German with Herzog talking to Laurens Straub. Herzog discusses, amongst other things, the circumstances which led to him making the film, making the concession to Fox to do 2 simultaneous versions, and, of course, Kinski. Brought over from the Anchor Bay DVD is The Making of Nosferatu (HD upconverted from SD, 13:06), which is a pretty fantastic vintage featurette that mixes on-set footage with an extended interview with Herzog. He discusses the challenges of attempting a genre film, especially a remake of an all-time classic. The interview is full of quietly bleak Herzogisms, like "All of my films come from pain, that's the source... Not from pleasure." Kinski is also glimpsed getting the Dracula make-up applied. There are also two moody trailers and a stills gallery included.

Fitzcarraldo

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras:

Extras:

The legendarily precarious production of 1982's Fitzcarraldo, chronicled in Les Blank's Burden of Dreams and Herzog's own My Best Fiend (see below), certainly looms large while viewing the finished product. Watching dozens of South American natives help to build a pulley system and operate it, so that a giant riverboat can be dragged over a mountain, it's hard not to wonder why they did it. It's unlikely enough in the fictional reality of the film, but the reason for the natives to help Fitzcarraldo is eventually explained by the story. Knowing that nothing on screen has been mocked up, and that all these Indians are actually putting their backs into it, all while risking their lives and dealing with an insane diva of a leading man, makes it downright startling that they stuck with the film production and that the movie turned out pretty great.

The parallels between Herzog and his main character are obvious. Like the filmmaker, Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, aka "Fitzcarraldo," has impossible dreams. He wants to build an opera house in the middle of the jungle in the early 1900's, and he's willing to make a potentially deadly foray downriver into hostile territory to make that a more plausible reality. As Fitzcarraldo, Klaus Kinski is generally quite likable, even when he seems on the edge of madness. Because it's madness with a purpose, madness stoked by a passion for opera, particularly the voice of Enrico Caruso, which Fitzcarraldo savors and shares through his phonograph. Claudia Cardinale, as Molly, a madam with a heart of gold, helps to make Kinski likable too, by bringing out his warmth. As Herzog says in his audio commentaries, she manages to bring a smile out of Kinski onscreen, which is rare in any of their films together.

Eventually, Fitzcarraldo (with financial help from Molly) gets a crew together and makes a trip with the intention of claiming an area full of untapped rubber trees, since they lie on the wrong side of some deadly rapids. Fitzcarraldo's plan is to sail down a nearby river with no rapids, then cross to the other side by dragging the boat across land where the distance between the two rivers is shortest. As they take their journey, the film somewhat resembles both Aguirre, The Wrath of God and Coppola's Apocalypse Now (which, of course, had a similarly treacherous production), with Fitzcarraldo and crew traveling deep into the jungle, constantly being watched by invisible eyes on the shore. Things turn out marginally better for Fitzcarraldo's crew than it did for Aguirre's, but not after plenty of anxiety and hardship.

In some ways, Fitzcarraldo is one of Herzog's more straightforward films. Fitzcarraldo has clear-cut goals, and he must make a hero's journey to achieve (or not achieve) them. That should not suggest that the film has a cookie-cutter mentality, but it does make it seem like an ideal gateway for new viewers looking to dig into Herzog's filmography.

Let's talk technical turkey. The Blu-ray features an inconsistent AVC-encoded 1080p 1.85:1 transfer that typically looks sharp and has nicely saturated colors, but also has noticeable digital noise in many moments, especially in darker shots. Some comments I've read online have really lambasted this transfer for this reason, but I looked at this movie on a couple different monitors, and it looked generally above average to my eyes. Audio-wise, we get English DTS-HD MA 5.1 surround and DTS-HD MA 2.0 stereo mixes in English and German (with optional English subtites). As with Aguirre, the actors are clearly speaking English on set, although both versions appear to have post-synchronized dialogue. Even with the 5.1 option for the English dub, the German version seems to fit the tone of the film better. All around, the audio sounds good, with the English 5.1 mix shuffling a little bit of atmospheric sound and musical score to the rear channels.

Once again, we get two audio commentaries. The English is with Herzog, his brother and producer Lucki Stipetić, and Norman Hill; the German, with Herzog and Laurens Straub. As usual, there's a fair amount of overlap in the anecdotes told in both commentaries, but as usual, Herzog has a good rapport with both of his conversation partners, making the redundancies easy to sit through -- even for nearly three hours. The disc also offers a trailer and a massive stills gallery.

Ballad of the Little Soldier

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras: N/A

Extras: N/A

1984's Ballad of the Little Soldier was co-directed by Denis Reichle, a photographer working in Nicaragua during the Contra War, who told Herzog he needed to come and make a film there. This short documentary examines the life of Indians in the Miskito tribe on the Nicaraguan coast, who have become soldiers. They initially fought alongside the Sandinistas, but at the time of film, they were opposed to them. The film captures testimony of people from various villages talking about the violence and killing they've witnessed, which, in many cases, inspired them to become soldiers.

The most striking aspect of the film -- the one which is referred to in the title -- is the training of children to be soldiers. In nearby Honduras, boys who are maybe ten-years-old are shown running through army drills, led by former Sandinistas (because they are the ones with formal military experience). They shoot off live ammo, the backfire vigorously shaking their little bodies. They shoot off mortars like they were learning to use fireworks. They plan to return to Nicaragua to fight against kids who have been kidnapped into fighting without any training.

Reichle, who was drafted into the Nazi's Volkssturm at the end of World War II, makes his horror at these conditions clearly known. He tells a drill instructor that these boys are just being brainwashed. The instructor, maybe because of a language disconnect, agrees that the boys are at a perfect age to be brainwashed. Herzog, though he provides narration for the film, does not broadcast his feelings about these events. He just lets the testimony and images speak for themselves. Even without direct commentary, these images are powerful and quietly horrifying.

On the technical side, the AVC-encoded 1080p 1.33:1 image is grainy and sometimes noisy, moreso than Land of Silence and Darkness, but it still rates quite well for a guerrilla-shot 16mm doc. Most of the dialogue is spoken in Miskito and Spanish, with Herzog giving a spoken translation over it. The German DTS-HD MA 2.0 audio (with optional English subtitles) is preferable, because it has a much more palpable presence, and listeners feel a better sense of stereo sound. The English DTS-HD MA 2.0 audio meanwhile seems like a mono mixdown, probably. It sounds less clear, not as atmospheric, and a bit distorted in places.

Where the Green Ants Dream

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras:

Extras:

In an Australian supermarket, a handful of Aborigines sit in the middle of an aisle in a circle. This was the spot where a sacred tree once stood. It was the spot where children can be dreamed, so the tribe needs to be in this spot, if they want to continue to have children. The supermarket manager jokes that it's good for business; if there are kids, there'll be more customers.

This small scene in Herzog's 1984 film Where the Green Ants Dream is pretty much the whole film in miniature. The white man takes from the Aborigines in the name of progress, and the Aborigines refuse to completely give in and leave -- out of tradition, ritual, stubbornness, whatever. In the main story of the film, a mining company is blasting through the desert, attempting to disrupt an area that is deemed sacred because it is where the green ants dream. If they are disturbed from their dream, the Aborigines explain, there will be drastic consequences for humanity. (The fact that the mining company is looking for uranium -- a key component in the construction of modern large-scale weaponry -- shows that this prediction might not be too far off the mark.) The Road Warrior's Bruce Spence stars as geologist Lance Hackett, who becomes the go-between for the Aborigines and the mining company. He tries to understand their viewpoint, while easing them toward a kind of settlement. The company just wants to throw money at the problem.

Herzog clearly finds some humor in the clash of cultures. At one point, the mining company brings the Aborigines to the big city to see the wonderful progress of the modern world; they end up buying them digital watches with alarms that no one knows how to silence and getting stuck in elevators twice. Eventually the tribe asks for a Caribou cargo plane, which the company readily supplies if it means a settlement; upon receipt, the tribe proceeds to light a campfire inside the plane.

Though it has a good heart -- and lots of memorable moments -- Where the Green Ants Dream fails to cohere into a powerful whole, leaving the aftertaste of a well-meaning but minor work.

The AVC-encoded 1.85:1 video is sometimes noisy, but is one of the best transfers in the set overall. No film damage, a high level of fine detail, and strong, vibrant colors. The English DTS-HD MA 2.0 audio has excellent fidelity, with no noticeable distortion. The mix handles the dialogue and music well. The occasional didjeridoo performance really exploits those low frequencies but doesn't blow out the woofers. The film also comes in dubbed German DTS-HD MA 2.0 audio (with optional English subtitles), which is very similar to the English track, although some of FX reproduction is not as fully realized as the original soundtrack.

The disc offers Audio commentary with Werner Herzog and Laurens Straub, which is in German with English subtitles. Herzog talks about the real-life inspiration for the film, which came from an Australian court case where Aborigines lost the right to some of their land to a mining company. He also discusses the background of many of the performers in the film. Most illuminating to me, he explains that the strange tape of soccer goals that Bruce Spence's character listens to is actually Herzog's own tape, which he would play when he needed a pick-me-up. A trailer is also included.

Cobra Verde

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras:

Extras:

In his documentary on Klaus Kinski, My Best Fiend, Herzog spends drastically less time on his final film with Kinski, 1987's Cobra Verde, than on the films that came before. Maybe the production memories were too painful, but it is an unfair slight to what is still a great collaboration between the two. As Herzog has noted, the film borrows some trappings from spaghetti westerns (Kinski had appeared in some during the '60s) to tell its tale of an infamous Brazilian bandit who becomes overseer of a sugar plantation and ends up a slave trader in West Africa. As Francisco Manoel "Cobra Verde" da Silva, with his hair grown out like a blond lion's mane, Kinski is in full-on alpha male mode. After his character is chastised for knocking up all three of his boss's daughters, Kinski spits at him, "Sugarcane planter, I am the bandit Cobra Verde." It's a hammy performance, certainly, but one which showcases Kinski's intensity and volatile energy in a way wholly unlike any of the work he had done with Herzog before.

When da Silva's boss sends him to Dahomey, in West Africa, to re-start the slave trade with the mad king who rules there, it is intended as a suicide mission. And, for a while, it seems like they might succeed in getting da Silva out of the way. The impetuous king first sends slaves to get da Silva settled into a nearby captured fort, then has him captured and brought for punishment. The king's men paint his face black because they cannot behead a white man. The only way he escapes death is the plotting of another member of the royal family, looking to seize the throne. da Silva is charged with training hundreds of Amazons to attack the king and seize the throne. Kinski seems completely in his element, stalking past dozens of fighting women in tribal outfits, flying into berserker rages and correcting their spear techniques.

If there's anything that might sits uneasily in the viewer's mind about Cobra Verde, it could be the final act of the film. da Silva has successfully led the coup and is now reaping the financial and fleshy rewards (he claims to be the father of 62 slave children). He doesn't seem happy, but that doesn't alter the icky feeling that comes from understanding that our (anti-)hero is now a successful slave trader. He was a jerk, sure, but we still sympathized with him for a little over an hour. Now, seeing da Silva check a chained slave's teeth, as though the man was a horse, can't help but make that sympathy feel misplaced. Herzog (and history) don't let him get away with it completely, since the slave trade is abolished and da Silva is left stranded in a hostile territory with little to show for it. Watching Kinski struggle to push a getaway boat into the water, while the boat is far too heavy for one man to move, is a poetic final moment for the former bandit Cobra Verde. Nonetheless, this ending for the film doesn't quite bring a feeling of balance, especially as the conclusion to not only Cobra Verde but the entire Herzog-Kinski collaboration.

The disc offers another excellent Audio commentary by Werner Herzog with Norman Hill. Most strikingly this time, Herzog describes the disintegration of his relationship with Kinski during the filming of the movie, largely because of Kinski's obsession with a project that Kinski ended up directing himself, Paganini. Also included is In Conversation with Werner Herzog and Laurens Straub (HD, 58:00), which is precisely like the featurette on the Woyzeck disc, except that this time, the audio-only German interview (with a still photo and English subtitles) is much more compelling to sit through. There is some anecdotal overlap with the English commentary (of course), but Herzog goes into much more depth in the talk, about the genesis of the project, the inspiration he took from Brian Chatwin's novel The Viceroy of Ouidah, and about Kinski. Also included is Herzog in Africa (HD upconverted from SD, 45:32), which is a totally illuminating excerpt from director Steff Gruber's documentary Location Africa. It provides a look at the production of the film, with a lot of fly-on-the wall scenes. This means footage of Kinski freaking out and Herzog looking fairly stressed-out. Herzog also gives a signature interview, where after describing his writing process, he disses Hollywood's approach, particularly for resulting in "lifeless films." Also included is a stills gallery and a trailer.

Lessons of Darkness

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras: N/A

Extras: N/A

1992's Lessons of Darkness is a documentary/fiction hybrid that takes footage of men fighting oil well fires in Kuwait and tries to re-contextualize it, as if these events were taking place on another world. Herzog's conceit works better as an organizing principle for his footage than it does for drama. After all, though few of us have been to Kuwait, the media has spoiled us enough that we can recognize footage of our own planet -- no matter how strange and surreal that footage is. In moments that recall both Fata Morgana and Ballad of the Little Soldier, Herzog grabs shots of wrecked satellite dishes and dinosaur-like bones in the desert and juxtaposes them with testimony of women who witnessed war-time atrocities.

Many of Lessons of Darkness's images are captured from a helicopter that glides over the desert, revealing the wrecked infrastructure, lakes of oil, and billowing clouds of black smoke and flame. Herzog also gets us down on the ground, watching the men from Boots and Coots (a company now owned by Halliburton) as they try to contain the giant geysers of flame shooting out of the earth. They shoot streams of water that turn to mist before even getting close to the flames. They fill a metal drum with dynamite and send it out on a giant crane into one of the fires. The most memorable moment in the film shows a worker re-lighting an extinguished well, over which Herzog deadpans, "Has life without fire become unbearable for them? Others, seized by madness, follow suit." This is the rare moment where Herzog's poetic fictionalizing is more powerful than the documentary footage; the director has said in interviews that they reset the fire to prevent the oil from gushing into other wells and causing a larger chain reaction, but the fictional idea of workers seized by fiery madness is definitely more suitable for the portrait Herzog has created.

The AVC-encoded 1080p 1.77:1 images are about on par with the rest of the documentaries in this set. A bit grainy due to the shooting conditions, but with pleasantly saturated colors, good contrast, and no discernible film damage. Lessons of Darkness has little in the way of diegetic speech; mostly, the soundtrack consists of classical music and Herzog's English narration and translations. The DTS-HD MA 2.0 stereo mix handles both of these elements quite well. It's a bit odd that only the English narration is available, considering that all of the on-screen titles are in German. English subtitles are also available.

Little Dieter Needs To Fly

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras: N/A

Extras: N/A

Little Dieter Needs To Fly, the 1997 documentary which served as the basis for Herzog's 2006 film Rescue Dawn, consists largely of a first-person monologue from Dieter Dengler, a naval aviator who was shot down over Laos in 1966 and kept in a prison camp for several months. Dieter became a pilot because he was in love with flying, not because he felt any compulsion to participate in fighting. Shown in his home in San Francisco, Dieter talks about his impoverished childhood, during which his family ate cooked wallpaper for the nutrients in the glue. Now, to keep his mind at ease, Dieter is overstocked on food and keeps provisions hidden under the floor of his pantry.

As Dieter's story segues into his captivity, Herzog takes his star to Laos to illustrate what occurred there, and more specifically, what he went through. Locals are dressed up as soldiers and given rifles to play the roles of Dieter's captors as he narrates what happened to him. Even though this is clearly being done for the benefit of the film, Dieter is shown getting a bit anxious to be back in this place and to be put into these situations.

Little Dieter shares pretty much the same structural bones as Rescue Dawn, and both even feature a similar mocking sidebar about the U.S. military's completely unhelpful instructional film about what to do if you get stranded in the jungle. Herzog is clearly immensely impressed by Dieter and his story, and together they guide us through the most painful, defining moments of Dieter's life with no phony melodrama and no excessive sentimentality.

A brief video-shot coda, depicting Dieter's 2001 funeral, has also been included at the end of the credits.

The AVC-encoded 1080p 1.77:1 video comes from a mixture of sources of variable quality. The modern footage is clean, with good color; it was shot in super 16mm, so it's a little grainier than some of the features, but of better quality than Herzog's earlier docs. Apart from some muddy slo-mo shots rendered through video, digital compression is minimal. The quality of the English DTS-HS MA 2.0 audio is a little variable because of the practical nature of shooting a documentary, but overall the soundtrack is clear and understandable. The music Herzog uses has a particularly rich, high-fidelity sound. English subtitles are also available.

My Best Fiend

Content:  Video:

Video:  Audio:

Audio:  Extras:

Extras:

Putting a perfect button on this immense box set is Herzog's 1999 documentary, My Best Fiend, which covers the director's relationship with his best-known actor, Klaus Kinski. Taking on the Dieter Dengler role from Little Dieter Needs To Fly, Herzog returns to various settings where he worked with Kinski to discuss memories of their fraught partnership, sometimes bringing in other collaborators to reminisce and/or commiserate. He even returns to his childhood home, where Kinski boarded for a few months. He describes to the current residents how Kinski once locked himself in the bathroom for two days and smashed everything inside to bits. Needless to say, this moment was foreshadowing of what was to come.

Herzog does not take a strictly chronological approach to his subject, peppering the film with incidents from the set of Fitzcarraldo, maybe just because Les Blank's Burden of Dreams outtakes were quite plentiful. While Blank chose to largely shy away from the outbursts of the blustery leading man in his making-of documentary, Herzog presents Kinski's violent, often meaningless on-set outbursts quite vividly and almost iconically. Years before Christian Bale famously blew up at a cinematographer for getting in his eyeline, there was the indelible image of Klaus, howling in the jungle about the terrible food to a production manager while the native extras looked on, frightened, and Herzog nonchalantly set up the next shot with his cameraman.

Of course, if Klaus Kinski was nothing more than an asshole, there would no reason to make five films with him. Klaus's leading ladies, Eva Mattes and Claudia Cardinale, are particularly complimentary to him, although Herzog chooses to shift the credit to these actresses for helping to tame Kinski and curb his more explosive tendencies.

Though Herzog spends a lot of time recounting all of Kinski's foibles, great and small, he is clearly fond of the man. When describing Kinski's signature approach to entering the movie frame while doing a half-spin, Herzog is clearly both amused and impressed by his former collaborator. Though he makes a point that Kinski would claim to be a "natural man," and then complain about every aspect of being in nature, Herzog still ends his film with footage of Kinski allowing a butterfly to flit around his head and fingers. He leaves us not with the insecure diva, but with the movie star who found peace and meaning through the moving image.

The AVC-encoded 1080p 1.77:1 video is quite strong, and -- despite the variety of film sources from which it is drawn -- is probably the most consistent-looking documentary in the set. It's not a particularly stylish film, but the transfer has a clean, colorful look. There are both German (with optional English subtitles) and English DTS-HD MA 2.0 audio options, with Herzog just narrating over his own German dialogue for the latter recording, in a style similar to the English tracks for Fata Morgana and Ballad of the Little Soldier. I remember this strange English dub from the old Anchor Bay VHS, and I would recommend staying away. It just becomes frustrating to hear Herzog talk over himself all the time. Subtitles all the way, I say. Both soundtracks sound just fine otherwise.

No commentary here, unsurprisingly. Just a trailer.

Final Thoughts:

Herzog: The Collection is close to a perfect box set. Some of the transfers are problematic, and many of Herzog's documentaries from this period have been excluded. That's the bad news. Here's the good news: this is an overwhelming collection of 16 films, that range from good-to-classic (and nothing less), often complimented by entertaining and illuminating commentaries by the auteur himself. This is a giant, vital chunk of cinema history, all in one convenient collection. DVD Talk Collector Series.

Justin Remer is a frequent wearer of beards. His new album of experimental ambient music, Joyce, is available on Bandcamp, Spotify, Apple, and wherever else fine music is enjoyed. He directed a folk-rock documentary called Making Lovers & Dollars, which is now streaming. He also can found be found online reading short stories and rambling about pop music.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||