| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

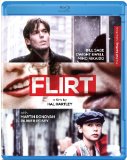

Flirt

Please Note: The images used here are stills provided by director Hal Hartley's Possible Films website, not the current Blu-ray edition under review.

Writer/director Hal Hartley (Henry Fool), with his pictures' eccentric ratios of cerebral, philosophically-minded intellectualism to wackiness and romance, is himself already something of an anomaly in the American-indie-filmmaker milieu, making his 1995 film Flirt, by far the most experimental and odd of Hartley's features, a curiosity's curiosity. Telling and retelling the same tale three times over, it's less a playing with narrative à la Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon and more an experiment in form in the manner of Hou Hsiao-hsien's Three Times; whereas in Kurosawa's film the concern is which of three versions of the same event is "true," Hartley thrice transports the (identical) events of his tale through space in the same way Hou had his same Three Times-told tale play out in different eras; the story remains the same, but the city, language, and culture is completely different in each telling. But is it really the same? Can it be, if certain "extraneous"/environmental factors are changed even though the characters and the events that befall them remain exactly the same? It's this intriguing question -- one that tests the limits of my favorite filmmaking truism-cliché, "It's not the what [the story] but the how [the details and style of the telling] that makes or breaks" -- that Hartley seems to be setting out to pose via his attempted experiment.

The film is thus an omnibus compiling three successive short films -- "New York, March 1993," "Berlin, October 1994," and "Tokyo, March 1995." Each of these episodes tells the story of a flirtatious person -- Bill Sage in New York, Dwight Ewell in Berlin, and Miho Nikaido in Tokyo -- who's given a commitment-ultimatum by a lover (Sage's is Hartley perennial Parker Posey, Ewell's same-sex amour is played by Dominik Bender, and Nikaido's is played by Hartley himself -- more on that later) being called away by work in a far-away city for six months. Each of the flirts also has a flame on the backburner (as any self-respecting flirt would), which in every case leads to the introduction of a gun into the scenario, a misfire from said gun, and the arrival of our flirt in the local ER for the treatment of a particularly nasty (and graphically discussed, if not actually shown) wound and, amid the chaos, a meditative, descriptive reverie, delivered as a monologue by the flirt, of erotic/romantic realization, which could mean either that the commitment-seeking lover is worth giving up the life of an "aimless flirt" for, or that an aimless flirt is the only way to be.

The result has many moments of genuine interest and some very fine visuals (Hartley's and DP Michael Spiller's camera adores their protagonists as they appear and move against the very specific backdrops of their respective cities, and Hartley's ideas when it comes to composition and framing are captivating and invigorating, as usual), but this is ultimately an experiment that lacks purpose: By the middle of the second (Berlin) segment, Hartley is already distracted from the idea he's reeled us in with, fatally digressing via a Greek-chorus group of German construction workers (one of whom is the very recognizable Lars Rudolph, who would go on to play the lead in Béla Tarr's great film Werckmeister Harmonies) who strike up an idle-chatter commentary on the film and the filmmaker we're in the process of watching. The commenting-chorus grouping has its direct counterpart in the other segments (it's comprised of patrons of a nasty men's room in the New York bit, ladies imprisoned on suspicion of prostitution in Tokyo. But this is Flirt's fatal first instance of self-reflexivity, which continues as a progressive slide throughout the often extraordinarily nicely-shot Tokyo segment (which contains what I think might be a fourth, much more abstract version of the story played succinctly and silently, with movement, in what appears to be a modernist-Kabuki class), in which Hartley appears as himself, the boyfriend of that segment's flirt, and in which a crucial sound effect is provided by a bright blue film canister we later realize is labeled "Flirt," and ostensibly contains the film Hartley's been shooting in Tokyo, i.e., the film we're watching. (Adding to the film's already teetering, overburdened tower of self-reference is the fact that Hartley and Miho Nikaido, the actress playing the Tokyo flirt, were a couple in real life as well as onscreen here, and were subsequently married.)

Certainly, there's nothing at all wrong with a film musing upon its own self (what would the classically great Godard's filmography be without self-reflexivity?), and at least there's a self-deprecating quality to the way one of those German construction workers stoically declares Hartley's experiment "already failed" (viewers will be hard-pressed to disagree). But Flirt's navel-gazing leads the film to an unbreakable impasse, neutering the basic conceit (why does each segment so punctiliously adhere to exactly the same dialogue and situation(s) if it's going to be distractingly and rather arbitrarily changed up in this way?), while adding little beyond an aura of cleverness that Hartley, who's been accused often enough (and quite unfairly) of just such posturing irony, is normally too good and inspired for. As it turns out, Flirt was initially only the first, New York-set segment, and Hartley subsequently received funding to make a feature from it. The three-times experiment was then grafted on a posteriori, and unfortunately, it shows; there's glimmer after isolated glimmer of Hartley's compelling way with a gesture, with odd and beautiful blocking, and with the fire-and-ice clash of the emotional and the cerebral, moments that do make the film worth at least a glance at any rate. But it all adds up to markedly less than the sum of its parts, which never quite fit together and sometime actually cancel each other out. Flirt is a bit of a flirt itself; it intrigues and allures, passes the time enjoyably and interestingly enough to lead you on, but ultimately frustrates with its inconsequentiality, leaving you hanging with its implied promises without ever really following through.

Video:

The transfer of Flirt presents the film at a widescreen 1.78:1 aspect ratio and does very well by Hartley's visual sensibility and Michael Spiller's cinematography, with its often stark lighting and bright splashes of color amid the muted urban palettes all coming through nice and vivid, all with a fairly good retention of the film's celluloid/cinematic look (erring, just maybe and if so only slightly, on the too-much-digital noise reduction (DNR) side) and very little compression artifacting (only some rare edge enhancement).

Sound:The disc's DTS-HD Master Audio surround track presents the film's sound with crisp, full clarity, unhampered by any muffling, distortion, or imbalance; the high and low ends of all music, dialogue, and ambient sound are richly and resonantly present and accounted for.

Extras:--NYC 3/94 (1994, 9 min.), a video (i.e., camcorder-level technology -- this was the mid-'90s) short by Hartley featuring some of the actors from Flirt (plus his future Henry Fool star James Urbaniak) in a vaguely detailed, mostly heard from offscreen, but actually truly frightening urban-apocalypse scenario. It's as much of an experiment as the feature, but perhaps a bit more successful; its use of sound is particularly ingenious.

--The film's theatrical trailer.

What begins as an intriguing experimental proposition in Hal Hartley's 1995 film Flirt -- the same story, of an "aimless flirt" confronted with the possibility of committed love and subjected to eccentric violence, told in three different cities with different actors, sometimes also switching around the genders but with more or less identical characters, dialogue, and plot -- loses sight of what makes it interesting and gets bogged down by the end in a few too many self-aware nudges and winks, becoming not much more than an overly sterile, self-reflexive game. It's not without its charms (foremost among them being Hartley's well-honed style, which makes for some visually and performatively very effective, as well as his politically refreshing nonchalance in considering male and female, gay and straight, European and American and Asian characters as interchangeable on at least some level without overemphasizing the novelty of that approach), but on the whole, it comes closer than any of Hartley's other features to being what his work has always been myopically accused of by his detractors: a cool, solipsistic, overextended cerebral exercise that's hobbled, not enhanced (as in Hartley's other films) by its airlessness, ultimately failing to reach our hearts or our minds in any very meaningful or memorable way. Rent It.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||