| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Amour

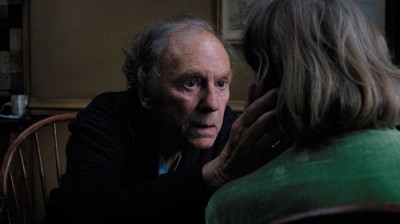

Please Note: The images used here are photos provided by Sony Pictures Classics and do not directly reflect the picture quality of the Blu-ray edition under review.

"A lot of rubbish is talked about love. You know what real love is? It's wiping someone's ass, or changing the sheets when they've wet themselves, and letting 'em keep their dignity so you can both go on." - dialogue from Terence Rattigan's The Deep Blue Sea

Q: When does an extreme, up-close, and sustained look into the private lives of an elderly couple being slowly but surely torn apart by one partner's death feel not at all like a violation, but more like a sobering, soul-cleansing, surprisingly far-ranging tribute to being human?

A: When it comes in the form of a cinematic dramatization that's been conceived and crafted by the exquisitely sensitive, rigorous hands of writer/director Michael Haneke (Caché, The White Ribbon).

Such is the case of Amour, the movie that brought Mr. Haneke -- an Austrian filmmaker who has worked in Austria, Germany, France, and the U.S. -- to a place neither devotées nor detractors (and there are plenty of both) likely would have predicted: Accepting an Oscar for Best Foreign Film earlier this year, and giving a U.S.-televised speech in his proficient but careful English (if you didn't catch it, he was like the anti-Roberto Benigni). This was something like a miracle: Haneke's gracious affability aside, his has always been, openly and decisively (he's quite literally said as much) an oppositional cinema -- often abrasive (his one noble failure, 1997's Funny Games, and its shot-for-shot English-language remake from 2008, being the prime specimens), always painstakingly conscientious and morally committed to disturb (all of his films from The Seventh Continent through The White Ribbon) art films that mean to engage and provoke the audience, not please or reassure in a way that could ever be mistaken for award-grubbing. And Amour, despite the significant ways in which it differs from much of his work, is no exception in that all-important regard. In telling the story of an apparently minor cardiac event/cognitive disruption and subsequent inexorable slide into death that befalls an elderly couple of former music teachers (the venerable duo of Jean-Louis Trintignant (My Night at Maud's; Z) and Emanuelle Riva (Hiroshima, mon amour)) and their middle-aged daughter (Isabelle Huppert, Heaven's Gate), Haneke once again stares down a harrowing, insoluble problem that everyone is very familiar with but that no-one can bear to dwell on too often or for too long; in fact, even more so than the insidious hypocrisies of contemporary Western life, culture, and society that Haneke sharply, relentlessly probes in most of his films, the concerns of Amour -- love and death, no pun intended -- are universal and inescapable, looming over us all in one way or another. But perhaps because of that largeness of theme, Amour does open up new vistas for Haneke's refreshingly, often beautifully astringent and clear approach: The director has made precisely zero concessions to sentiment or pleasantry to pull off his most widely embraced and vaunted film to date, but he has come, perhaps inadvertently and clearly organically, upon the story that allows him to remain as bold, as oppositional as ever, while at the same time accommodating an aching, open, unabashed tenderness unprecedented in any of his other work thus far.

Amour's story is neither new or narratively complicated; it is, in a certain salient respect, the oldest and simplest story there is. When Anne (Riva) experiences a moment of lost time one day at the breakfast table across from her husband of over 40 years, Georges (Trintignant), it's fleeting, but it signals the end of the active-senior's life -- proudly attending concerts starring world-famous former piano students, doing the shopping, being generally engaged and mobile in their affluent retirement -- we've briefly glimpsed at the beginning of the film. It's the emotions that are endlessly difficult and complex, and that's what Haneke has so succinctly and sensitively limned here. There's no suspense about what will become of Anne: The whole film is a recounting of the events leading up to the one haunting pre-credit image, of Anne in her final repose, with which Haneke brings us into this experience. And that's just what it is -- something we live through with Georges, Anne, and the guilty, panicked, unaccepting Eva (Huppert), something horrific but beautiful, the decline into invalidity and death of a wife and mother throwing into very sharp relief the truth, the authenticity, and the inexhaustibility of her and her husband's love as he faces ever more painful choices about how to care for his wife, how to relieve her of her awful suffering, and how to let her go. As the film becomes confined to Georges and Anne's well-appointed apartment, we settle in for an observation of the day-to-day as Anne's condition worsens (that's the invasion of privacy referred to in my opener above), and the narrative takes its inevitable course -- minor immobility but still-bright sentience giving way to paralysis, dementia, force-feeding, loss of bodily-function control, wailing and terrified/terrifying unrecognizability leading up to the point of the unbearable for both husband and wife -- we are also treated to a kaleidoscopic view of this couple's comfort with each other, their familiarity, their annoyances, their casually brutal honesty, and their reflexive care for one another. Haneke and his actors, playing the bittersweet music of Haneke's crafted-down-to-the-essential script, show us fully and roundly what's at stake even as they depict its cruel, slow, biologically-mandated slipping away, and there's simply never been anything, no depiction of romantic/eternal love, more affecting put on celluloid: The fruits of Haneke's unwavering banishment of any easy sentiment or banal platitudes or reassurances about the human spirit is a pure, clear, penetrating, and overwhelming emotion.

Beyond that masterful conjunction of dialogue, narrative, and performance, there is Haneke's supremely honed, refined style to maximize the film's emotional power. In the same way he neither spares nor indulges anything in the acting or the story, Haneke never falters in giving us exactly what is necessary, no more and no less, in his pacing and blocking of scenes, in his framings and cuts (made with unflagging economy and exactitude via his habitual editing team of Nadine Muse and Monika Willi). Not surprisingly, this literary aficionado and veteran of the theater is fond of citing theater revolutionary Bertolt Brecht's resonant maxim about true simplicity being the most involved, excruciatingly complicated thing to achieve, but Haneke (and hardly for the first time) pulls it off: Each tiny detail of each minutely composed interior shot, each gesture, each sound, each interaction, has been narrowed down from the infinite choices to the one perfect, inevitable-seeming way of being, so that it's all incredibly dense, solid, immediate, placid yet unfathomably deep -- unimaginable any other way after we've seen it conducted by Haneke. As restraint yields immense emotion in the story, so too does simplicity and silence accrue a devastating power on the aural and visual planes (the latter courtesy Haneke's inspired and exceedingly proficient D.P., Darius Khondji, who's also been responsible for the look of such diverse other pictures as Panic Room, several The Immigrants, and Haneke's own U.S. remake of Funny Games). And just as Haneke respects these characters (and us) too much to trivialize them through overemphatic contrivance or too-easy intimations of emotion, so too does he exclude all non-diegetic music from the soundtrack, so that when we do hear the music played and appreciated by these inveterate music lovers -- as when the characters do, finally and unavoidably, betray their unwanted, overpowering grief -- it's something rare, precious, truly sublime, and profoundly moving.

Amour is the most expansive, and perhaps the flat-out finest (a difficult call to make with such a singularly impressive filmmaker) act of cinematic sublimation Haneke has yet performed. Its overarching purpose -- to clarify, to investigate as honestly as possible what hangs in the balance when we're talking about human relations -- is in no way at odds with that of the rest of his filmography, and yet there's a more readily discernible sort of honestly-earned reprieve from the disillusion, wincing exposure, and even pessimism here than in much of his previous work, the result not of any compromise but of his foraging, rigor at every level fully intact, bravely into more intimate, more "personal," and thus riskier territory (riskier on his terms -- easier prey for the false hope and delusory contrivances he avoids at all costs). There's a famous, disconcerting pun in French that relies upon the similar sound of the word for love from which this film derives its title and the word for death ("la mort" mistakable, in speech, for "l'amour"), but the fact that this film that stares every physical detail of decline and death -- and its accompanying emotional trials-by-fire -- so unflinchingly is also entitled "love" has nothing to do with sardonicism or irony; this is a film that's serious to the nth degree, and makes itself worthy of every second of its seriousness. According to Amour's subtle, mysterious, almost unbearably moving ending, we can probably never know for certain whether or not love is stronger than death as the saying goes, whether or not it disappears at that final moment when our consciousness ceases. But whether or not there is, perhaps, some trace of a love like Georges's and Anne's that lingers on, that really is as immortal as true love can feel to us, we can at least be certain of one thing: The value of a work of art as perfectly achieved as Amour, with its true, profound, and thorough tribute to the emotion after which it's named, is, for whatever it's worth, as close to imperishable and eternal as it gets.

Video:

This widescreen transfer of Amour, retaining the film's original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.85:1, is excellent. Haneke's style is all about clarity, and every bit of the naturalistic feel cinematographer Darius Khondji brings to the images (via highest-quality high-def digital video of the latter-day, "cinematic" -professional variety) is present and accounted for. More, this is an unusually "dark" film in the literal sense, with many a lowly/dimly-lit or nearly-black interior scene, but even in those dark moments detail and solidity of colors, shapes, and figures is impeccable. The visual presentation of the film is top notch.

Sound:The disc's DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround track (in French with optional English subtitles) is also of practically perfect quality: Haneke is hardly one to overload his soundtrack (as typical for him, there is absolutely no non-diegetic sound), but the sonic space, the dialogue, the very finely-honed and strategically executed sound effects (the fluttering of wings, the crash of a door being broken open at the beginning) ring out richly, fully, and beautifully at all points, with no distortion or imbalance present at any point to mar the film's perfect soundscape.

--The Making of Amour (25 min.), a very good behind-the-scenes documentary featurette by Yves Montmayer. There's some very candid, fascinating footage here capturing the process of making the film (in, for a surprise revelation, not a real Parisian flat but a studio-built apartment replica surrounded by green screens, not at all dissimilar to David Cronenberg's use of similar magic for A Dangerous Method, not that you can tell in either film in its finished form, where the technology is seamless and unobtrusive), with Haneke working with the actors in a rigorous, nitty-gritty way that lets us see what infinitesimal precision he's looking for in performance, in movement, in blocking, and in composition. This is juxtaposed with interviews with Haneke and his lead actors, in which Riva and Trintignant both express the novelty of working with a director so committed to fine-tuning and exactitude, whereas Huppert, having worked with Haneke twice before, is more philosophical, contemplative, and in-depth regarding his approach. It's a concise, succinct, very enlightening look, both in action and upon reflection, at Haneke's special alchemy.

--A conversation/Q&A with director Michael Haneke conducted by critic Elvis Mitchell before an audience in L.A., covering Amour in part but delving into Haneke's entire cinematic career as well. Mitchell, the German-speaking Haneke (ever relaxed, amused/amusing, and thoughtful in his responses), and the translator between them set up an easy, bantering rapport as Mitchell tries (sometimes with success, sometimes to affable bemusement) to bridge Haneke's austere ideas and absolute rejection of easy/simplifying commonplaces with a newspaper critic's/readers' need for broadly recognizable categories and definitions. It's actually great, pleasant fun to watch, never rancorous despite underlining, in a revealing and fascinating way, a certain inbuilt tension between Haneke's rather severe authorial understanding of cinema and Mitchell's broader-ranging, more easygoing cinephile's/critic's sensibility.

--The film's U.S. theatrical trailer, along with a handful of other previews for Sony Classics releases like the unmissable Before Midnight.

The great writer/director Michael Haneke's ongoing commitment to an unblinking, deeply aware, and brutally honest cinema goes to new, more intimate and personal places in Amour, and while it's not always easy to watch (nor should it be; even at its most painful, it always feels precisely and ineffably right), it's tremendously moving and powerful in a way very, very few films are. Haneke brings his usual, acutely and ruthlessly observational way of telling a story (in both the narrative and stylistic senses) to bear on that of the trials endured by the strong, abiding, true love between a long-married couple of cultured seniors (French-cinema royalty Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emanuelle Riva) in the wake of the wife's illness, debilitation, and irretrievable, erosive slide toward death. Haneke's camera is scrupulously avoidant of anything remotely approaching exploitation or cruelty, but it doesn't flinch for a moment from the harsh physical and emotional realities of the dreadful situation, its confusion and loss and humiliation; that kind of unremitting honesty, however -- that kind of acknowledgment of the painful, irremediable fact of death -- makes for the most stirring, principled, and meaningful illustration possible of the truest meaning of love, the kind that goes much deeper and wider, and endures longer, than romance or joy or even togetherness. That kind of love, its implications when all pretense, comfort, and everything extraneous have been stripped away (and Haneke doesn't neglect to quietly, respectfully, and sadly observe that this particular artistic, affluent couple has perhaps had more than their fair share of buffers from the brute physical facts of human life), is nothing short of prohibitive when it comes to even thinking of depicting it, let alone doing justice to it. But Haneke, with his penetrating intelligence and allergy to sentiment or coddling, makes good on his unusually lofty ambitions, and the emotional truths he is miraculously able to get to are among the rarest treasures the cinema has ever offered. In a filmography marked with sublime, unsettling, and impeccably conscientious (both morally and aesthetically speaking) achievements, Amour may be the most purely sublimated, note-perfect, and emotionally catalyzing masterpiece of all. Whether or not it's the best thing Haneke has ever done (and it's unequivocally in the running), it is in any case the work of an ingenious filmmaking artist working at the top of his extraordinarily intelligent, highly serious, graceful, and stealthily but steadfastly humane game. It's a great film -- one worthy, even at this early stage of what's sure to be its long existence in the hearts and minds of sensitive movie lovers everywhere, of being considered a classic. DVD Talk Collector Series.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||