| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Comment Ca Va

Please Note: The images used here are taken from promotional and other materials and do not directly reflect the picture quality of the current Blu-ray edition under review.

Comment ça va? (How's It Going?) is an audacious experiment from the height of director Jean-Luc Godard's long-running collaboration with his life/creative partner, Anne-Marie Miéville, with whom he co-directed a trilogy of features through the '70s and '80s in a similar formally innovative, minutely deep-thinking vein (the peak example from which remains the middle entry, 1975's Numéro deux). In this outing, made in 1976 but not released until 1978, Godard and Miéville avert their penetrating, politically charged camera gaze from the dovetailing, inextricable issues of ongoing socioeconomic/gender disparity and political apathy revealed so ingeniously in Numéro deux and turn it to a more introspective purpose (from their own political POV), exploring the complacencies, blind spots, and hypocrisies plaguing their own "side," the by-then moribund leftist political coalition/apparatus salvaged from France's failed revolution of 1968. Combining video and film, narrative and documentary approaches in witty, incisive, and inspired ways, it's a soul-searching film in which the work of holding oneself to one's ideals in a true, meaningful way -- of having integrity, of following one's own prescriptions -- is carried out as a sharp, complex analysis of ideology, mass media, and technology.

It's a kind of analysis that Godard and Miéville, certainly savvy enough to know that their medium allows such an analytical project to be carried out in full view, transparently, yet with a virtually inbuilt suspense and engagement for the audience, realize can accommodate a kind of hook, a "story," too -- an entryway for their audience into the urgency of their political, philosophical, and aesthetic questions (with the additional insight, arising from their very composition of frames, mise-en-scène, and montage/structuring of the film, that any line dividing those categories is blurry, indeed). So they us Odette (played by Miéville herself) as a documentarian working for the Communist Party who has to convince her immediate higher-up in the party (Michel Marot) that the video segment she's produced for party-member enlightenment, featuring this boss himself as he visits the office of the communist daily and takes charge of a story to be published in that issue, should be released with its complexities and gray areas intact, not butchered to the simplistic party-line parroting preferred by the Party powers-that-be ensconced in their headquarters and making all the decisions. The narrative form Odette's travails take is epistolary, related in a voiceover-narrated letter from Odette's overseer to his son, an actual laborer whose blue-collar life we also view glimpses of, in counterpoint to that of his father. We come to realize, over the course of the film, that this is in some way a letter of reconciliation between father and son, political insider/activist and the one he's supposed to be representing but from whom he's become remote and alienated.

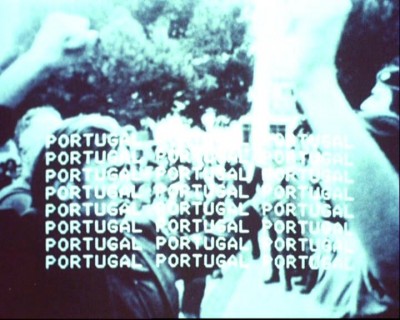

It's the long, involved argument with Odette alluded to in his letter -- an interaction between documentarian and powerful subject that constitutes a very large portion of what we witness in the film -- that has catalyzed this well-meaning but intellectually slack party employee to rethink his relations and interactions, both with Odette (and those in her position) and with his son (and those in his position). Odette and her boss sit at a monitor reviewing the footage she's shot of him dictating and making editorial decisions at the newspaper, the only mobile figure with any agency in a roomful of typists who transcribe his words and other underlings who carry out virtually unchallenged the incorporation into the next issue of the photo and caption he's concocted with automatic haste, under a deadline. The way Odette has shot and edited his work and the process of reduction and falsification it represents (the punning juxtaposition of the words "information" and "deformation" runs throughout the film) stands as a challenge to that haste, that undeservedly authoritative and thoughtlessly automatic response to news events (in this case, a lazily grandiose text ennobling and embalming the photo of a Portuguese striker in action as he stands up to a military or police figure, when the photo itself contains multiple other details and tells an infinitely more complex, difficult, disquieting, and actually relevant story). We see, over and over, Odette's footage of what transpired at the newspaper; she focuses her boss's (and our) attention on the labor of those typists, pointing up some intrinsic that's bothering her between the ideals of covering the world journalistically from the egalitarian-fraternal left of the political spectrum and the actual form and conditions of newsroom practice. (Odette even takes out a typewriter for a replay-experiment, asking her boss to think about what the typist's hands are doing and what his eyes are doing as they take in the photo and he invents and dictates his caption; the difference between hand and eye, between doing and seeing/dictating, is something she feels should be addressed.)

The documentary segment submitted by Odette and being viewed and argued over in their little room constitutes the part of the film shot on video -- her footage, both in edited and unedited forms, as well as her involved, compare/contrast manipulation, for her boss's provocation and benefit, of the shots she's taken of the photo of the protesting Portuguese striker and of a similar snap the paper ran several years prior of a French striker in a similar situation. As she uses the televisual editing apparatus to alternate and combine these two photos in various shapes, overlaps, and superimpositions (which play out for us as part of the movie), she asks and cajoles her boss (and, by extension, us) to really, deeply consider what specific meaning that photo of the Portuguese worker has to the paper's French-Communist readership, beyond the Party's pretty but hollow pronouncements and parroting of its own worn-out, simplistic go-to language. In a way, this is a belated fulfillment of a flawed project Godard had worked on with Jeanne-Pierre Gorin in 1972, the 50-minute study Letter to Jane, in which the two filmmakers used their camera to dissect a single still photograph of Jane Fonda (star, alongside Yves Montand, of the directorial collaborators' wonderful feature of the same year, Tout va bien), and their voice-over commentary to indulge in what too often comes off as quais-misogynistic, vindictive celebrity-bashing. In Comment ça va, though, the actual intended implications lost in Letter to Jane's misstep into biliousness are clarified and fulfilled; it's a highly detailed, tautly focused, and endlessly interrogative illustration that any impatient rush to assign meaning to a journalistic photo or documentary image is a recipe for sloppiness, simplemindedness, and hypocrisy; deadlines are artificial, and one must lose one's arrogant and presumptuous haste, slow down, and really strain to see all the implications and all the possible meanings in the visual or textual information being transmitted and arrive, through tortuous vetting, at something closer to the impossible-to-reproduce real story, something nearer to a truth.

As I've tried to articulate above, despite its openly didactic intentions, Comment ça va? never indulges in the open-and-shut sloganeering of which it's so highly critical. It's also not the dry, dull, grim visual slog such intentions might imply: Thanks to Godard and Miéville's collaboration with their longtime DP Walter Lubtchansky (who also shot the other two films in this triptych, Ici et ailleurs and Numéro deux and would go on to even further greatness over the ensuing decades, shooting Claude Lanzmann's Shoah and Jacques Rivette's La Belle noiseuse): The scenes of Odette's boss's laborer son as he and his girlfriend live, work, and play together are quite lovely (especially beautiful are the delicate compositions with the young man seated in front of a café window, framed almost in silhouette with the natural light entering from outside as he composes a letter of his own by pencil, in contrast with the newsroom typists' mechanical, alienated "writing"). The visual strategies used for the interiors with Odette, the boss, and their monitor (frequently cutting us fully into the documentary footage being reviewed and argued over, then back out so we can watch the boss and the documentarian watching and discussing) make for striking, rich, and very well-considered plays between quite modest degrees of color and light against shadow; this recalls both Godard's beautifully minimalist use of two figures, dark space, and sparing but carefully directed light in his 1969 film Le Gai savoir and, excitingly for its incongruousness, Citizen Kane, with Miéville as an investigative figure whose face we never really see (we see the back of her head in medium-wide shots or over-the-shoulder views of the boss as they debate/discuss; in the less-frequent moments when she's shot frontally, her face is swallowed up by shadow). If Godard, after his towering stint as the ringleader of the '60s French New Wave of cinema, had set himself on a quixotic, self-exiled odyssey in search of his own Rosebud -- the cinematic conception and practice that would do right by his seemingly contradictory aesthetic, philosophical/metaphysical, and political ideals -- and making a few futile stabs in the air along the way (e.g., the aforementioned Letter to Jane), then Comment ça va, with its bracing, radical, fully realized and focused experimentation , finds him closer than ever to attaining that driving, elusive goal.

Video:

This 1.33:1 aspect-ratio presentation of Comment ça va is more than passably faithful to both the celluloid grain/texture of William Lubtchansky's 16 mm cinematography and the blurry, primitive (to contemporary eyes) black-and-white videotape employed for the "documentary" sequences. Some apparent "glitches" at some cutting points appear to be endemic to the source material (possibly to the original, traces from the editing table itself) and not a reparable occurrence (and minor in any case), but there are no compression artifacts (pixellation, aliasing, edge enhancement/haloing) to speak of.

Sound:The disc's DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 sound (in French with non-optional English subtitles) is entirely up to snuff and faithful to the film's original mono, with everything as clear, immediate, and multidimensional as it would have sounded originally, and with no distortion, imbalances, or other audio flaws.

Extras:None.

Intellectual rigor and formal inventiveness, thy name is Jean-Luc Godard; as if we didn't already know, but his and Anne-Marie Miéville's 1976 (not distributed until 1978) film Comment ça va? (How's It Going?), newly released on Blu-ray, is a most welcome reminder. It's the last of the life/creative partner's '70s trilogy of feature-length "cine-tracts" that innovatively blur the lines between fiction, documentary, and protest film (preceded by Ici et ailleurs and 1975's Numéro deux), and it packs an additional sting because, through their story of a documentarian working with a French Communist Party newspaperman, they locate what they're calling to task -- lazy thinking, simplistic reliance on presuppositions and ready-made slogans, cults of personality, and self-aggrandizement -- not among any of the dismissible fools the right has to offer, but in their own leftist political comrades in the Communist establishment. This indirect self-examination lends an urgency and immediacy to the film's poring and sifting over party hierarchy, bureaucratic process, and rhetoric, its attempt to discern and resurrect the connecting lines -- between party and workers, between workers of different times and places, and, at its most philosophical, between deed, word, and image -- that have been buried by hypocrisy, despair, and lack of diligent, deep thought and critique. If it's those qualities that are missing, they're generously re-supplied by the film's fascinating, often beautifully shot/edited dissections of the workings of media (of any political bent), and how fragile and easily abused is the power of the published, disseminated image and whatever words, whether honest/clarifying or deforming, accompany it.

It's heady stuff, conveyed through a chilly, scrutinizing, unblinking aesthetic and emotional temperament, yet it's intoxicatingly engaging and galvanizing, both to look at and to hear. Godard and Miéville's film isn't just an expressed imperative to look more closely, to be better informed, slow down, and exercise further caution in our interpretation of any visual or textual information from any source; it's a rich demonstration of that imperative in action, an illustrated example that, for all the film's formal/philosophical rigor and openly didactic experimentation, follows one of the most oft-repeated classic rules of narrative cinema: It doesn't just tell us what it thinks is being done wrong and how we should go about changing it; it uses the medium's resources with wit, vigor, and carefully channeled but real passion to actually show us some engrossing, provocative examples of how. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||