| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

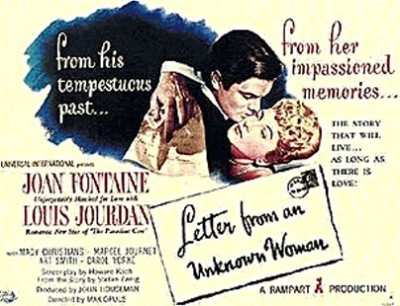

Letter From an Unknown Woman

There's a permanent, irresoluble tension that runs through all of director Max Ophüls's great, at once ornate and melancholy postwar films, from the perfect triptych Le Plaisir to what Andrew Sarris once called the greatest movie ever made, Lola Montès: the conflict between the seductive, undeniable beauty of an illusion and the concurrent, harsher but truer reality that's given rise to it. Ophüls put what was perhaps his first fully realized, wholly immersive experience of that tension onscreen in 1948, during his Hollywood exile (Ophüls was a German expatriate/refugee from the Nazis), with Letter from an Unknown Woman, a melodrama that reminds us how ill-used that word is when it's employed as some sort of default pejorative. The film certainly does offer generous portions of the swooning romance one associates with melodrama; integrated seamlessly as it is with Ophüls's inimitable narrative and aesthetic gracefulness, intelligence, sophistication, and sensitivity, however, this is a melodrama that draws every drop of richness available to the genre, upping the stakes immeasurably with a strong undertow of self-awareness and insight. The intense, intoxicating power with which Ophüls is able to orchestrate the story's push and pull tears us, as its heroine is torn, between romantic illusion and the bigger, deeper, darker truths it emerges as a response to and tries to mask, with only crushingly partial success that is in some ways more destructive than outright failure would be.

Ophüls and screenwriter Howard Koch (The Letter, Casablanca), working from a 1922 novella by Stefan Zweig, open their tale sometime in 1900, somewhere in a nicer part of Vienna, on the late-night, drunken return to his penthouse flat of Stefan Brand (Louis Jourdan, Gigi), a dashing middle-aged gentleman, once a renowned musician, now a profligate, decadent, womanizing wastrel who, on this particular rainy night, has had too much vodka and gotten himself challenged to a duel, no doubt by the husband or lover of one of his women. His caddishness habitual, Stefan has no "honor" left to defend and plans to skip out before the duelling hour arrives; he's caught up short, however, when his mute valet (Art Smith, In a Lonely Place) presents him with the letter of the title, which opens with "By the time you read this letter, I may be dead." In perhaps the most gorgeously rendered, aptly conceived flashback structure in any movie, ever, the contents of this missive take Stefan (and us) back, years and years before, to the moment he moved into his fashionable apartment as a young man, a piano prodigy full of ambition and promise for the future, to install himself in his well-appointed Viennese penthouse. Also residing in the building, in a considerably less spacious, impressive, and elevated unit, are a struggling, pensioned widow and her fair-haired teenaged daughter, Lisa (Joan Fontaine), the girl who will grow up to be the "unknown woman" who wrote the letter, and who will always consider the moment of Stefan's arrival in her too-small world the moment of her second birth -- her entry into real consciousness, her passing from adolescent whimsy to the seriousness of truly joyful, truly painful grown-up love.

It's no passing fancy. From that moment, Lisa lives only for her idea of Stefan, taking what some might consider a mere crush with the greatest, most obsessive, near-religious solemnity -- a true, deep devotion of which, Stefan slowly and seriously realizes as he reads and the letter's story unfolds onscreen, he has always been foolishly incapable, in any circumstance and at any level, whether emotionally or vocationally. As the retrospective timeline of Lisa's love for him plays out, we see how tragically, ruthlessly faithful Lisa has been to the innate, unimpeachable superiority she thinks Stefan represents, from her rigorous course of self-education/improvement undertaken with the aim of making herself worthy of the cultured and cosmopolitan hunk upstairs; to her near-refusal to leave when her mother remarries, with economic sagacity, to a businessman in a far-away town; to her flat-out refusal of the equally good bourgeois marriage to a high-ranking military man her parents have arranged for her; to her return to Vienna, where she works as a model in a dress shop and timidly presents herself and her undying, indestructible feeling to the love of her life, whose life, in its turn, has many disposable loves, but who is especially taken with this particularly eager specimen. Their affair is intense; Lisa has finally fulfilled what she believes is her destiny.... But, of course, it's only temporary, and when Stefan is called suddenly out of town on a concert tour, leaving his easily-made promises of a swift return to Lisa floating away on the air like so much steam as his train whisks him away from her forever, she's left alone, abandoned, and pregnant with their son. Lisa is able to find a forgiving, upstanding officer to marry her and raise Stefan Jr. (succumbing, after all, to her prescribed role); she lives a charmed but empty life as a society lady, relieved at her husband's kindness and devoted to her son -- the one piece of Stefan she can have and hold -- until the fate in which she so sweetly, foolishly has faith crosses her and her ultimate love's paths once more.

Even as she's fully cognizant of Stefan's squandered promise and washed-up-gadabout state, Lisa's long-suppressed feeling remains; she's willing to sacrifice everything for him, just as she always has been. In the scene that climactically, horrifically drives home the uncrossable chasm that's always existed between them, Lisa is invited back to Stefan's flat after they spot each other at a concert; as it dawns on her that he vaguely remembers her but that he really has no idea who she is, that she is an "unknown woman," her heart finally and irreparably breaks. She's written the letter Stefan is now reading from a Catholic charity hospital where the sisters attend her as she dies slowly of the same typhus that has taken her and Stefan's son (an illness with which both mother and son were brought into contact by the same new, industrial-era "connector," the railroad, that first consigned Lisa to being out of sight and mind for Stefan); it trails off on one last, unfinished/unspoken "if only...," with a stern note from the nuns tacked onto the end informing Stefan of the worst. All he can do, finally, is offer his own belated, too-little version of the adherence to self-destructive, tooth-and-nail, romantically conceived but brutal honor that Lisa has demonstrated unto death, and the film ends on a suicidal gesture as the same carriage in which he arrived carries him off to the duel that, the true extent of his lifelong blindness now illuminated, he no longer has any reason to avoid.

From the film's opening sequence, in which Stefan's handsome profile is framed through a carriage window, and in countless ingenious ways throughout its remarkably swift running time (under an hour and a half, amazing considering how elegantly transitioned and balanced each of the numerous plot points is), Ophüls never ceases to make his trademark astonishing, sublime use of all the cinematic resources at his disposal, principal among which are (in addition to the fantastically tortured Jourdan and Fontaine's pure, stoical lovesickness) Franz Planer's (Criss Cross) brilliantly lit and composed cinematography; editor Ted Kent's (who also worked on Criss Cross, as well as Bride of Frankenstein and My Man Godfrey) supple, elegantly economical transitions; and the unforgettably melancholy melodies composed by Daniele Amfitheatrof for the score. This band of synchronized artists, with Ophüls as their masterful ringleader, powerfully maximizes both the dreamy allure of the pretty surroundings in which the characters move (a movement constantly, dizzyingly articulated by the director's renowned "gliding camera," which seems always to be making an elegant lateral pan to follow the characters' movements whenever it's not smoothly pushing in or pulling out for unbelievably well-composed reframings) and all the ways in which their apparently free movement is delimited and circumscribed by that same fine, rigid world, with all its unspoken expectations and narrow mores.

On two memorable, separate occasions, Ophüls places Stefan and Lisa in a frame with curtains drawn to each side: their own feelings and senses of individuality are subsumed by the play, written by the culture and society of which they're inextricably a part, in which they're bound to be performers. The sets (courtesy Alexander Golitzen, who would go on to design Touch of Evil for Orson Welles), as captured in Ophüls and Planer's compositions, create physical barriers within the frames (a common visual idiom of the movie melodrama, Ophüls's mastery of which would only be rivaled, later, by fellow Germans Douglas Sirk and Fassbinder); Lisa hears Stefan before she ever meets him, and when they do first lay eyes on each other, it's through a partition created by an open glass door standing between them, walling off their physical connection in a way the entire building seems subsequently to do, with all of its windows, bars, and balustrades. The staircase to Stefan's apartment, upon which Ophüls's fluid camera glides once more to follow Lisa's movements, is both an ascent to her illusory heaven and an inevitable descent back to her inescapable purgatory (stairways and vertical hierarchy, as well as emergence from shadow into light, are significant in Ophüls's use of space throughout, as they are in much of his work). In a deservedly much-remarked-upon scene (Scorsese, for one, singled it out in his Personal Journey through American Movies), Lisa and Stefan's first forays into giddy, reckless courtship takes them to an outdoor fun fair, mostly abandoned for the winter, where they sit in a static train compartment as the scenery of various luxe and exotic locales, powered by a poor old carny's pedaling, rolls by outside the window; it's eerie, beautiful, touching, and subtly devastating in its glorious but temporal artifice -- just like the entirety of the film (and, one might hear Ophüls whispering if one listens closely, all fictions, all films).

The purposeful, never merely superimposed stylishness with which Letter from an Unknown Woman is gratifyingly replete marks it as one more full, fluent, haunting expression of Ophüls's cinematic voice, which, when at its strongest (which it very often was, and which it unequivocally is here), offers something rare and wondrous: romances, spectacles, heightened fictions whose own self-awareness and relentless auto-critique never sap a single watt of emotional energy, instead enhancing the felt reality of their stories' emotions, longings, impossible dreams, and tragic disappointments until they -- and, by seemingly effortless extension, we, the enthralled and enraptured audience -- are practically spilling over, full to bursting with affective engagement and responsiveness. As well as any of Ophüls's numerous equally astonishing creations, Letter from an Unknown Woman is a pean to the miraculous moving-picture possibility of artifice without lies, excess without waste, and bittersweet truth through the most delicately, enchantingly florid fiction.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

Presenting the film at its original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.37:1, Olive's AVC/MPEG4-encoded, 1080/24p-mastered transfer of the film is very nicely done indeed (and I say this as someone who owns the also good region 2 DVD version of the film, to which this new release compares quite favorably). The film mostly looks pristine in all the right ways, with the celluloid texture left intact via an admirably steadfast avoidance of too much digital noise reduction, and an almost entirely clear, sharp, unmarked image save for a few scattered, random, barely noticeable instances of scratches and visual pops, and one slightly bothersome line that appears at the left side of the screen for a brief stretch at one point, not marked enough to be an insurmountable distraction. In the final analysis, this Blu-ray of Letter to an Unknown Woman offers significantly better-looking picture quality than might be expected, and the distributor has decidedly done right by Ophüls's and cameraman Frank Planer's bedazzling imagery.

Sound:The DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 soundtrack brings the film's original mono sound home with great clarity, fullness, and resonance, without any distortion, imbalance, crackle, popping, or hissing noted.

Extras:None.

Now finally released, after a much too long period of unavailability, in an excellent Region 1 Blu-ray edition that does justice to its many distinctive visual qualities, Max Ophüls's Letter from an Unknown Woman is one of those films that seems more legendary to anyone who's actually seen it than it's managed to be in reality...thus far. As you experience the troubling cinematic delectations of this picture's almost unbearably unrequited love and tragically doomed turn-of-the-20th-century romance between a dissipated Viennese composer and an eternally, unwisely loyal woman burdened with the task of making impossible dreams a reality, you'll likely wonder why this excellent, ravishing movie isn't at least as well-known and widely beloved as Casablanca or Gone with the Wind, either of which it bests in atmosphere, emotion, narrative assurance, overpowering performances and unforgettably elegant camerawork. It's not too late to give it its proper due, however; now is every collector's chance to add Ophüls's Hollywood masterpiece to the recent home-video revival that has brought his European masterworks like The Earrings of Madame de... and Lola Montès to their rightful places on the shelf of any conscientious North American cinephile. Like virtually any of Ophüls's supremely emotion-saturated, visually splendiferous, uniquely intelligent, and endlessly re-watchable exemplars and investigations of cinematic spectacle and romance, Letters from an Unknown Woman casts a sweet, sad spell you'll want to succumb to again and again. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||