| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Vivre sa vie - Criterion Collection

THE MOVIE:

An impressionistic review written in homage to the inspirational spirit of the source material. A criticism in six tableaus.

1. THE CHURCH OF CINEMA - ANNA KARINA MARTYRED

It's not that Jean-Luc Godard wants to remind us that we are watching a movie because he wants us to differentiate motion pictures from real life, it's that he wants to confuse the two. In his worldview, the two should be one.

And so his 1962 film, Vivre sa vie (My Life To Live) begins by seemingly falling apart. Only a couple of lines in and Nana, our savior, played with a convincing naturalistic ease by Anna Karina, seemingly flubs a line, repeats it, tries it a number of different ways. No, Godard has not included a blooper to throw us off, but rather, he has inserted a reality of cinema into the reality of his cinema. Nana is an actress, she is practicing a line. It's one of life's bloopers.

Nana's life takes two important turns in the movie, both precipitated by cinema. One happens early on when she goes to the movies to see Carl Th. Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc, the 1928 silent film starring Falconetti, an icon of early French cinema. During the sequence, as Nana watches a scene from the movie with tears in her eyes, "Falconetti" is the only word uttered. There is no other sound, and her name is spoken reverentially, whispered by...who? Later in the movie, Nana will talk about her desire to live in silence, and the true value of words will be debated. Shortly after, she will be in a silent film herself. Literally. Though this time accompanied by music.

The second invocation of actual cinema comes after, when Nana and her pimp, Raoul (Saddy Rebbot), are supposed to go on a date to the movies and do not. Raoul is discussing business. Directly relating to that first movie, it's right after seeing Joan of Arc that Nana decides to become a prostitute to pay the bills, her dreams of being a film star failing; in the case of missing this later trip to the pictures, she meets the "young man" (Peter Kassowitz) as a result of the detour, and he arguably becomes the one person to have affection for her after her life dovetails. It's certainly when it becomes clear that at least Raoul doesn't care about her. He's the only man in the room who does not dote on Nana.

Raoul is merely a pawn, though, this is about Nana. It's by no coincidence that Anna Karina's character shares a name with the heroine of an Emile Zola novel and, perhaps more importantly, a silent film adaptation directed by Jean Renoir in 1926. The previous Nana was an actress who became a kept woman, and who then destroyed herself and the man who kept her. She is part of a sprawling fictional history invented by Zola, just as Godard's Nana is part of his own history and also the history of cinema. This is why her story is told as a series of religious tableaus, the 12 Stations of the Passion of Anna Karina. Vivre sa Vie begins with multiple angles of Karina's face shown under the opening credits. We view her in the same abstracted light as Dreyer showed us Falconetti. She is to be revered, admired, worshipped. And she will die for our entertainment.

2. IN HIS OWN WORDS

The summary Jean-Luc Godard wrote for the original release of the movie, reprinted in the Criterion booklet:

"A film on prostitution about a pretty Paris shopgirl who sells her body but keeps her soul while going through a series of adventures that allow her to experience all possible deep human emotions, and that were filmed by Jean-Luc Godard and portrayed by Anna Karina. Vivre sa vie."

Note the expanded credit the filmmaker gives himself: "Thought out, written, shot, edited, in sum, directed by Jean-Luc Godard."

3. KIDS WITH GUNS

The men in Vivre sa vie don't hang around, that's true. Even the ones Nana has a relationship with, including her ex Paul (Andre Labarthe), with whom Nana has a child, don't last. This is by Nana's choice more than theirs, however. She discards the date who bought her the ticket to see Joan of Arc, trading him for a skeevy photographer. He prefigures the pimp, Raoul, in that he has his own designs on what he will acquire from Nana--the photos he wants don't really seem to be for her, and we never even see them--and then he goes. Godard is drawing a direct parallel between a film actress and a prostitute, both give up something of themselves for the pleasure of others. He is fascinated by the connection moreso than he intends to make it a negative. The guilt is on us.

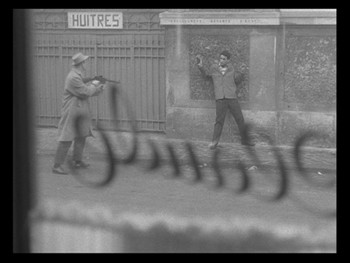

The very mythology of movies seems to be unfairly balanced. Why do boys get to be the gangsters and the girls unwitting pawns in their childish games? Godard himself famously boiled cinema down to girls and guns, and time and again he shows his overgrown adolescent heroes engaging in gunplay (see also: Breathless, Band of Outsiders, Pierrot le fou). In this mythology, girls are interchangeable, either the femme fatale or the kindly caregiver/romantic. Is it then a surprise that, by being neither, Nana will ultimately be punished? As someone who swaps men around, the ultimate disempowerment will come when Raoul swaps her--though, since he trades her for cash, arguably it's what he's been doing all along. To further push the idea of entertainment as a similar illicit transaction, consider how easily we now acquire, consume, and discard our films. I've owned Vivre sa vie on VHS and one DVD prior to this. How different, how transient, will the interaction with Nana be when she's available for download on demand?

4. ART AND BEAUTY ARE LIFE - THE SACRIFICE

There is, of course, the question of the male gaze in cinema. Raoul Coutard's camera is as in love with Nana as we are. The way he lingers on her face, often posing her against a white background (again: see Dreyer and Falconetti; also, compare the black of the theatre's darkness while Nana watches the film), it's as lurid as it is worshipful. Is it then a coincidence that the pimp and the cinematographer share a name? One can't deny that Godard is aware of the abstraction art makes of its female subjects. When Nana's admirer finally speaks, he reads from Poe's "The Oval Portrait," the story of a painter who becomes so obsessed with the portrait of his beloved that he is creating, it eclipses the obsession with the woman who originally inspired this passionate impulse. To the point that he doesn't realize that while bringing her to life on his canvas, she has died.

This reading is sandwiched within the two silent film sequences with the boy, and Godard makes the connection clear. The declaration that the woman is dead is a reminder of the last words we see on the screen in the clip from Dreyer. Joan of Arc is asked "And your deliverer?" to which she replies "La mort." Death.

Anyone who has seen enough Godard movies should instantly recognize his gravelly voice dubbed over the young man's. It's the director who is reciting Poe, not the actor. This directly inserts the artist in his art, confirming his awareness of his inherent role in the breakdown of his character and also dismissing another division between life and art. His opinion of himself and of men in general does not seem very high at this point: even those who might profess to love Nana use her to satisfy an aesthetic need. The boy is in love with being the one looking at her. Since Godard and Karina were married at this time, what is he doing by making her the fetish objects of his films?

There are several moments when the gaze is turned back on us in Vivre sa vie, but one is the most striking. In the café just before Nana meets Raoul, Anna Karina looks directly into the camera, and her eyes seem to be asking us, "Can you believe this? Is this enough?" Godard has tricked us, though, and he flips it again. Nana is actually looking at a young couple seated across from her. They appear to be in love, but they also look like they are in distress; it's ambiguous. Then Raoul's cohort plays an overly sentimental pop song on the juke box. It's a song called "Ma môme" by Jean Ferrat. "My Kid." It's a mawkish ballad about the love for a child framed in romantic language.

Godard seems to be undercutting Nana's dreams here. She is giving up romantic love, giving up her role as a mother, giving up her dreams to be an actress, and choosing to be something else. Just before she does so, her friend Yvette (G. Schlumberger), another single mother who has turned to prostitution, reveals that the husband/father that abandoned her was last seen as an actor in an American movie. A man gets his dream, the woman is left holding the bag. Just after all this, there is a gunfight in the streets, so violent the very sound of the machine gun fire shakes the screen. Warning, Nana: Danger Ahead.

5. THE UNWITTING PHILOSOPHY

Make no mistake, Nana does make her choice, good or bad. This is at the root of how Godard can maintain that she has kept her soul. The other woman, Yvette, is willing to blame outside circumstances for her current occupation; Nana very clearly is not. She says straight out that she does what she does by her own power and it is thus her responsibility. It's the core of existential thought: you decide how you go on in this life, and when you do, live with it. "Escape is a pipe dream," Nana tells Yvette. "It just is."

"It just is." It's very simple, but if we are to see Nana/Anna Karina as a religious martyr, we need to understand that she represents determinism. "It just is." It's like DeNiro in The Deer Hunter: "This is this. This ain't something else. This is this. From now on, you're on your own."

Being on one's own is important to Nana. Let's think about how Godard frames the conversations she has with the men she is attached to. In the start, when she is with Paul, we never see their faces. Godard and Coutard shoot the pair from behind, and we see only a glimmer of Nana in the mirror on the other side of the bar. The camera moves back and forth between them, not dominated by either. In the next sitdown, when Nana meets the photographer, she asserts a little more control, and though the camera is once again behind them, the actors are turned to give us a side view.

Next, there are two conversations with Raoul. The first is in the café when he is playing Nana for a fool. Wanting to know if she is "a lady or a tramp," he decides to insult her. If she gets mad, she's a tramp; if she laughs it off, she's a lady. (Yeah, that's one sick mode of thinking.) He is seducing her (indeed, the whole scene, with the unknown couple and the Ferrat song, is a seduction), and he stays mostly out of frame, he let's her be the focus. When they meet again, with Nana sitting in front of a large photograph of Paris, as if she were somehow representing (encompassing?) the whole city, Raoul sits across from her, so that his back is to us and we can see her face. The camera still moves back and forth, though, but somehow it captures less and less of Nana. As Raoul takes her over, she is almost totally obscured from our view.

Unsurprisingly, Nana also becomes obscured from herself. At one point in the movie, she says, "I...is someone else." It's almost a non sequitur, a bit of a Freudian slip, but it's a true philosophical expression, and one that we can't help but recall in Vivre sa vie's most memorable scene. In the penultimate tableau, Nana meets an old man in a café. After inquiring about what he is reading, Nana joins him at his table and they have a discussion about the meaning of discourse and one's ability to express oneself. The man is played by the real-life French philosopher Brice Parain, and in this scene, he extends the theory that our ability to express ourselves is directly related to our ability to know ourselves. Language is only as faulty as our ability to think, since thought is inseparable from our vocabulary.

The conversation between Nana and Parain is the only time in the movie that someone takes Nana seriously as a person. The old man doesn't want to sleep with her, take photos of her, or earn money off her. He doesn't expect her to find the records he's after like the customers in the record store where she worked, nor does he pity her the way that the police officer who interrogated her pitied Nana. He simply wants to talk to her and share ideas, and in the process, Nana reveals herself as a deep thinker. She is a bright individual not just in the mental sense, but in her whole aura. Talking to Parain, she positively glows, as if she is coming alive. The only other time we have seen her this active is when she is rebelling against Raoul in the pool hall, when she meets the young man and dances around the room to a song of her choosing. Of course, the irony is that this could be seen as what Raoul will punish her for. His given reason is that she refused a customer, but the subtext is that she dared think for herself.

Parain's validation actually gives Nana permission to think for herself, but also permission to make mistakes. He says that we must "pass through error to arrive at truth." More simply, we have to mess up in order to learn how to be better. As a deterministic force, Nana must remember that it's okay to acknowledge a misstep and correct it. She even seems to be trying to do so by accepting the affection of the young man and deciding to leave Raoul's "employ." This, however, is when the movie shifts into silent movie mode. She is now Falconetti, now Joan of Arc, and her crazy ideas of self-actualization threaten the male establishment.

6. FIN

In terms of style and form, Vivre se vie is one of the more exciting and lively Godard films from the 1960s, even as it is also one of the most melancholy. This is a sad movie, one that even questions the very possibility of happiness. It may be less playful than some of Godard's other films from the period, but he trades that for a tighter control. Vivre se vie strikes me as the film where the director was most in command of the production, where he knew each move and calculated how that move would affect the overall whole.

This seems necessary on his part if we are to accept Nana as a metaphor for cinema, and that the start and end of this movie is to be the star and end of a singular life. Indeed, the very last shot seems to show us the camera itself dying, as if wounded by the gunshots that just rang out. In the last seconds, the camera drops its gaze, as if it were gasping its last breath, before smashing to black and the last title card: FIN. It has a devastating effect, but one that is also exhilarating, akin to religious ecstasy. Martyrdom crystallizes the cause, makes way for reinvigoration and rebirth.

Nana gave herself for the sins of cinema, and Anna Karina and even Jean-Luc Godard have subsumed themselves to the force of the narrative on her behalf.

THE DVD

Video:

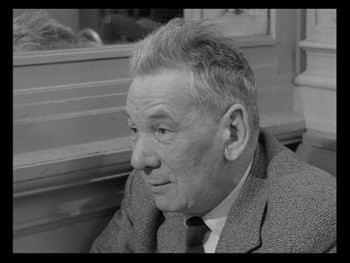

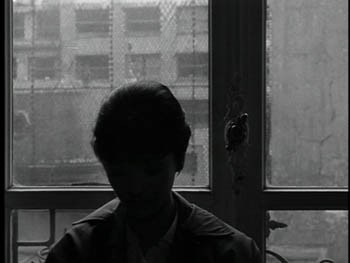

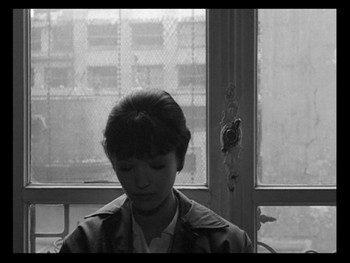

If there was ever a disc in your collection you needed to replace for a newer version, it's the 1999 Fox Lorber version of My Life to Live for the Criterion Vivre sa vie. Just popping the old disc on and scanning through it, I saw so much dirt and so many scratches, I almost thought I should check my cable connections to make sure there wasn't something wrong. Not that I needed to cast a glance backwards to see how marvelous the full screen transfer (1.33:1 aspect ratio) on the Criterion disc is. The beautifully rendered black-and-white image is so crisp, so clear, and so full of nuance and depth, I am not sure that people seeing Vivre sa vie at its premiere in 1962 saw it looking this good.

Don't believe me? Just look at these comparisons of the old disc and the new one. I specifically chose scenes where darkness was a factor so you could see how the proper contrast allows so much more detail to come through.

(l to r) Koch Lorber, Criterion

(l to r) Koch Lorber, Criterion

Also look at how the Criterion "picture boxing" allows for more image area than the straight full-screen transfer.

Sound:

An equally fine clean-up has been done on the original French soundtrack. The mono mix on this disc is pristine and clear, with good balance and no distortion.

New English subtitles appear in white on the screen and are removable. The writing is clear with a nice colloquial style that reads as modern without being anachronistic.

Extras:

We get the usual round-up of excellent extras and packaging from Criterion. The disc for Vivre sa vie comes in a clear plastic case with a gorgeously designed double-sided cover. The interior booklet has a lot of goodies, including the summary I quoted above and Godard's original scenario for the film alongside excerpts from a 1962 interview with the director. Another vintage article is Jean Collet's writing on the movie's soundtrack, and we also get a new essay by critic Michael Atkinson. The 40-page booklet is full of photos, the original credits, the chapter titles (which correspond to the movie's title cards), and on the last page, the musical notes for the theme written by Michel Legrand.

On the DVD itself, outside opinions on the film come in the form of a full-length audio commentary by Adrian Martin, detailed in its dissection of Vivre sa vie, as well as 45-minute interview with Jean Narboni from 2004, wherein the film expert contextualizes this movie in terms of Godard's evolution and talks about his overall reaction to the movie.

There I some vintage material on the DVD, as well, beginning with a 1962 interview with Anna Karina (11 minutes) shot for French television a few months before the release of Vivre sa vie. She talks mostly about how she met Godard and the myth that it was through an advertisement that he was looking for a girlfriend. Faire Face: "La Prostitution" was a 1961 television show about prostitutes that features the author and lawmaker Marcel Sacotte, who wrote the book on the subject that inspired Godard to make this movie; 21 minutes, 45 seconds of the program is included here and sheds light on the reality around Vivre sa vie. An essay with photos by James Williams goes into further detail about this book, which supplied the lecture about practices in the trade that we hear in voiceover in the movie. This is presented as two galleries, text and photos, navigated with your remote. The photos show a clear inspiration on Godard for the visual style of Vivre sa vie.

A stills gallery shows handsome black-and-white photos from the film set (including one with the director) and promo material, and we also get Godard's original trailer, a must for any DVD of a '60s JLG joint. This one is set to a rock 'n' roll soundtrack and has comical touches like bars over some actors' eyes and a zippy montage that make the film look like a screwball romantic comedy.

FINAL THOUGHTS:

DVD Talk Collector Series. One of Jean-Luc Godard's best finally gets a DVD release worthy of its quality. The Vivre sa vive - Criterion Collection disc puts the complex, creative film together with some excellent bonus features that give it context and add to the pop experience of Godard and his muse Anna Karina on an artistic high. It goes without saying, though, that the true star of on the disc is the film itself, and by that I mean the material of the film in terms of narrative and presentation. The restoration here will make you feel like you are seeing it for the first time, even if it's your fourth (as it was mine). Absolutely vital.

Jamie S. Rich is a novelist and comic book writer. He is best known for his collaborations with Joelle Jones, including the hardboiled crime comic book You Have Killed Me, the challenging romance 12 Reasons Why I Love Her, and the 2007 prose novel Have You Seen the Horizon Lately?, for which Jones did the cover. All three were published by Oni Press. His most recent projects include the futuristic romance A Boy and a Girl with Natalie Nourigat; Archer Coe and the Thousand Natural Shocks, a loopy crime tale drawn by Dan Christensen; and the horror miniseries Madame Frankenstein, a collaboration with Megan Levens. Follow Rich's blog at Confessions123.com.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||