| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

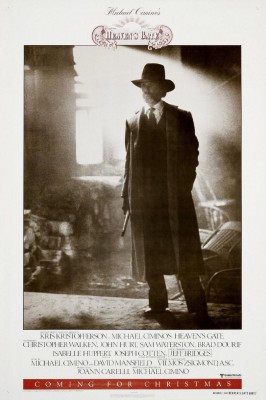

Heaven's Gate: The Criterion Collection

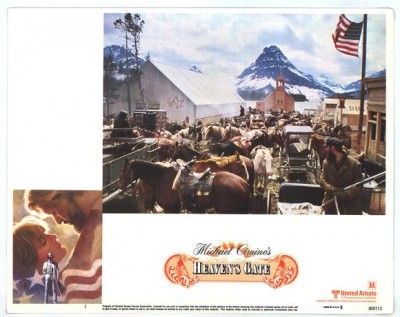

Please Note: The images used here are from stills provided by The Criterion Collection and promotional materials, and are not taken from the Blu-ray edition under review.

The "failure" of Michael Cimino's expensively-made box-office disaster Heaven's Gate is something that's been questioned more and more seriously, and been progressively reappraised and revised, virtually since the time of its release in 1980, when the bulk of critics and almost all of the public (encouraged by very loud, vitriolic "buzz" purposely created by studio suits who, in seeing a visionary but arrogant auteur like Cimino fall on his face, had leverage over unruly, artistically-minded directors to gain) rejected it unequivocally. As early as 1982, L.A. celebrity-cinephile Jerry Harvey was showing it on his much-loved local cable channel (this reviewer's first-ever taste of Heaven's Gate came courtesy of Xan Cassavetes's documentary The Z Channel, which recounts Harvey's legendary cable-TV curation of important, neglected, and/or forgotten movies); the late Robin Wood, a thoughtful, erudite, and highly informed critic, praised it in much depth and detail and named it his third-favorite film of all time. Now The Criterion Collection, in direct collaboration with Cimino, has, for the very first time ever, restored the film (which underwent a harrowing butchery at the insistence of the studio upon its initial theatrical release) to Cimino's precise vision for it, and it turns out that the studio, the critics, and the public were wrong (and not for the first time; thank goodness we have DVD/Blu-ray now to correct these errors, however belatedly). Heaven's Gate is not quite an out-and-out masterpiece, but it's so supremely ambitious that even its little flaws intrigue and seduce. It's a highly original vision that's been realized on film with an aesthetic vim and vigor that's absolutely breathtaking, to the point of being nearly all-encompassing; gargantuan, ambitious, and conflicted, it's a deeply American film, and a worthy recipient of what would turn out to be the last chance the more creatively adventurous big-studio Hollywood of the '70s would give to a star American director for a very, very long time.

Heaven's Gate's distinctly American turning-point moment is the late 19th century, its place the immigrant-settled boom towns and fields of Wyoming, its big canvas the westward expansion that, via the then recently completed railroads, was bringing hordes of poor, starving immigrants, recipients of free land, to the open spaces of the American West, with a resultant struggle playing out between the profiteers who wanted the land for their lucrative cattle concern, and the masses, who wanted to live on and farm their jeopardized property. The particular place Cimino has located this widespread struggle is Johnson County, Wyoming (the site of a similar real-life "war" of the period between settlers and cattle barons, which Cimino has transmogrified into his illustrious epic), and the figures whose lives occupy its foreground in the film are a prosperous madame, a French immigrant named Ella Watson (Going Places's Isabelle Huppert, in her first American role); Nate Champion (Christopher Walken), a son of immigrants ashamed of his roots who means to improve himself and is socially mobilizing by working for the cattle barons as a mercenary killer of the "anarchists" and "thieves" in his former community; a friendly Casper, Wyoming saloon/roller-rink operator (Jeff Bridges) who tries and fails to mediate the tensions between his immigrant customers and those who mean to kill them and take away their land; and, most prominently of all, a deeply torn federal marshal, James Averill (Kris Kristofferson). The internal conflict that consumes the good-hearted Averill has to do with where he comes from and where he -- and his country -- are going. The film actually opens 20 years before Averill arrives in Casper, where he'll be waylaid on his way to some other legal duty to the north; when we first meet him, he, along with a drunkenly rebellious valedictorian classmate (John Hurt) who will eventually, reluctantly find himself in the company of the well-off cattle barons, are participating in the elaborate rituals of a Harvard commencement (presided over by none other than American classic-cinema screen legend Joseph Cotten (Citizen Kane) as the school's dean/Reverend). This is a long opening, with elaborate crowd scenes, dances, etc., that envelops us in the atmosphere of both privilege and optimistic hope for the future that Averill has come from, before cutting ahead 20 years to show us how close he might get to where his bright-eyed younger self meant to go.

As a high-up law-enforcer, Averill's conundrum is that of all liberal do-gooders with sincere good intentions whose aim is to help the oppressed, if always from the outside: His commitment to justice is deep and true, and he's not afraid to get close to, live with, and eventually fight alongside the downtrodden for whom he feels (a community of Slavic and German settlers, of whom 125 have had their names put on a list by a cattle baron, Frank Canton (Sam Waterston) for execution -- a list that the influential Canton has gotten approved by both the governor and the President, making the struggle a familiar one to us, i.e., a plutocratic America vs. a poor/working America). But Averill cannot really be inside the shoes of the beleaguered; his insecurity, his Achilles heel and potential downfall, is that he is always, albeit against his will, insulated from a true understanding of them and their experience. This problem is present throughout, and indeed, at the film's conclusion, it's revealed to be the deepest, most terminal attribute of both Averill's life and of the U.S. itself. In the meantime, however, Averill being stuck with one foot in his aristocratic roots and one in his masses-supporting, social justice-seeking present reality is a conundrum thrown into sharpest relief in Averill's personal life, as he forms one vertex of a lopsided love triangle that also includes Nate and Ella. In one sense, the triangle is a traditional one: The woman is desired by both men, so she is at the peak. In the more intriguing and finally more meaningful sense, though, it's Averill whose authority and obligation, gained through his wealth and privilege, holds him above and remote from Nate and Ella, who are in reality more on each other's level, despite Nate's perverse joining up with the same murderous plutocrats whose kill-list pointedly includes Ella's name. Cimino's conception of them and the actors' all-around excellent performances manage to make these characters work at once as emblems and as idiosyncratically detailed individuals: When Huppert's Ella says to Averill, "You'll never understand" when she tells him she means to accept Nate's marriage proposal, we know why she said what she said and why she's doing what she's doing, even though our heart and hers breaks for the noble Averill. Nate, perhaps even more than Averill, is wrenchingly caught between two parts of himself, finally becoming the film's most complicated character, a fact brought home by Walken's performance; his famously sinister aspect comes in handy for the cold-bloodedly murdering Nate, but his skinny, wide-eyed fragility comes into play, too, making it one of the actor's most complex and moving roles.

The love story, as it plays out with Ella learning to drive the new carriage Averill has bought for her and with Nate showing Ella the little cabin that he's literally "wallpapered" with newspaper by way of making a home for them both (and where he surreptitiously, touchingly teaches himself to read and write when nobody's looking) is as beautifully shot as it is played by the actors. As he did for The Deer Hunter, Cimino has recruited Vilmos Zsigmond to do the film's cinematography, and the results are superlative; the same unique, gauzy quality that Zsigmond's lighting and lensing brought to Brian DePalma's films of the period imbue Cimino's images, too, to a wholly different and even more ravishing effect, whether he's capturing shafts of light shining through a train window or into an empty saloon to highlight Averill's shadings; giving us a panoramic view of a Harvard courtyard before circling his camera around among the also-spinning dancers (a play he makes, too, in the film's central, joyous, community-defining skating-rink scene, with the hopeful new arrivals to America in joyous play and bathed in warm, bright, dusty-yellow tones that do as much for the film's "period" authenticity as the sets, costumes, and hair); or contrasting a foreground of lavender flowers to a vast backdrop of green fields and snow-capped mountains. You've rarely, if ever, seen vistas, in Westerns or any other film, the way Cimino and Zsigmond do them here; perhaps even more miraculous are the stunning visual qualities with which they invest "smaller" scenes, such as the hearth-glow that saturates Nate's and Ella's intimate moment after he shows her into the cabin he hopes will be their future home.

Averill's crusade to help Casper's and Johnson County's soon-to-be-slaughtered immigrants encounters many an obstacle, not only at the personal level with Ella and Nate, but also in the legal and political realms, with the power accreting almost entirely on the cattle barons' side (not to mention the problems that arise from tensions within the non-monolithic migrant community itself). All the wrangling, argument, and reversals over the stock growers' demands and the community's needs finally culminate in the film's epic battle scenes between the posse of murderous cattle growers on one side and Averill, Ella, Nate (who has finally found himself on the right side, i.e., the wrong side of the barons, and pays the ultimate price for it), and the defiant immigrants defending their American dream on the other. The effort is communitarian, strong, beautiful despite its violence, morally right -- and, after the whole massive, dynamic, painstakingly and magnificently shot-and-edited battle is over, a failure. The majesty, both vast and intimate, that Cimino has created with his story and the way he tells it is ultimately not that of triumph, then, but that of noble failure. There can be no happy end to Cimino's American tale: Averill is left standing, but all of his friends and loves, from whom his wealth, authority, and privilege had kept him separate even when he was fighting alongside and ready to sacrifice his life for them, are (and, the film is powerful enough to convince us, always will be, until the push back is widespread and strong enough) at the mercy of the worst members of his class. Averill, a fortunate son if there ever was one, is spared, but for what future? He ends up right back where he started, minus any optimism or motivation; rarely have the lush trappings of affluence been so troubling in cinema as when we cut rather abruptly from the horrific, tragic, heartbreaking events that end Averill's stay in Wyoming to a decade or so later, when the film closes on him floating listlessly, accompanied by a wife (the young lady from the opening/Harvard sequence) and surrounded by ornate fixtures and luxuriant furnishings, on a yacht somewhere off Rhode Island. That this ending resonates so well as a rhyme/response to the opening sequence points up the film's subtle, gentle, yet deliberate organization; despite its energy and immediacy, Heaven's Gate is nothing like the "mess" it's been unfairly characterized as, but a film of well-thought-out patterns and structures. Its visual motif of a group encircling and/or striving toward a center is prominent in the opening Harvard dance, the central skating-rink sequence, and the climactic battle, and it is significantly bookended by two brief but very meaningful scenes that both take place in the same privileged and wealthy milieu from which Averill emerges -- the first one crowded, ebullient, full of rebellious hope and energy, but the second adrift, isolated, comfortably defeated.

Heaven's Gate thus achieves in the end, if not any obvious "evenness" (it's extravagant throughout, and if you divide it into the traditional thirds, the first and the last are many times briefer than the embattled middle), then an odd, remarkable, daring symmetry. Its initially puzzling, apparently remote beginning and ending, with their suggestive and intuitive (and bleak) relation to the rousing experience and defeat Averill experiences while seeking justice in the Wild West, brilliantly bind together Cimino's entire teeming, earthy, vibrant, violent, bloody, galvanizing tale of the entrenched greedy vs. the hardworking newcomers into a loosely-tied but unforgettably engaging whole that both inspires and rewards reflection. The long (3-1/2-hour), thrilling, intensely involving experience of the film will wear you out, but that's warranted and feels right for a work this richly packed and expansive in scope; it's a picture big enough in its conception and execution to be successfully half-elegiac and half-damning without undermining itself, and the loving way in which each and every scene and performance has been crafted keeps you hanging on as their cumulative, exhausting, elating effect get down into your bones and lingers. If, as Cimino has stated on many occasions, his role model was John Ford's sublime, ambivalent Westerns, then Heaven's Gate, if not its characters' quests for contentment and justice, has to be considered an only slightly qualified triumph: There wasn't, and still hasn't been, a more provocative, rich, complex, and sadly disquieting Western since The Searchers.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

Criterion's and Cimino's new, painstaking high-definition transfer (AVC-MPEG4, 1080p) of Heaven's Gate presents the film at its original 2.40:1 widescreen aspect ratio. It almost goes without saying that it's a thousand times improved from the tossed-off, untended-to prior MGM DVD release (which was not even anamorphic -- always a crime, but particularly so with a film of Heaven's Gate's visual properties). But it's actually even better than that, almost entirely flawless; there was one near-subliminal instance, near the end of the roller-skating sequence, of flashing digital noise followed by several moments of a thin, static-y vertical line running down the left-central portion of the image (due, perhaps, to insurmountable damage to a piece of film Cimino still felt warranted inclusion?), but that is 10 or so seconds of a nearly four-hour film. The rest does full justice to Zsigmond's breathtaking cinematography: skin tones look natural; all shades of light yellow, brown, and shadow are distinct in the frequently dim interiors; and the landscape and battle-scene exteriors give us with great vividness Zsigmond's luxuriant take on Wyoming's (actually, Montana's and Idaho's) brilliant-blue open skies with bright-white clouds, golden fields, billows of coal-powered train smoke, etc. In addition, no over-tampering with digital tools has noticeably stripped away any of the film's celluloid texture/grain. It's a virtually perfect visual treatment that lets us truly see Heaven's Gate in all its intended, intimate and epic glory.

Sound:The film's soundtrack, originally in Dolby Stereo, appears here as a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround track that does a fine job of preserving the surprisingly deep undertow of David Mansfield's music in a resonant, sparkling-clear way, and the chugging-train and battle-scene sound effects all bold, booming, and deep, all while retaining Cimino and his sound designers' intentionally muted, overlapping Altmanesque approach to dialogue recording (every last word isn't necessarily audible, but, as in Heaven's Gate's most obvious predecessor, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, it doesn't seem that it was meant to be).

Extras:--A 30-minute illustrated audio conversation with Cimino and producer Joann Carelli, in which, over stills and scenes from the film, the two longtime collaborators recollect the many aspects of preparing and shooting Heaven's Gate, and Cimino delves in surprising detail into his modus operandi and approaches to filmmaking (he claims not to be "intellectual" or "political," but to start with the characters and just "see where they go.").

--A 10-minute on-camera interview with Kris Kristofferson, in which the now wizened, impeccably sincere and heartfelt actor/musician lovingly but honestly recounts his involvement with and impressions of the film.

--An eight-minute interview with soundtrack arranger/performer David Mansfield, with the musician, who was quite young at the time, discussing his fond memories of his surprisingly extensive involvement with the film (he and a band that also included T-Bone Burnett appeared on camera and were there for much of the shoot) and the way its musical vision was developed and realized.

--A nine-minute interview with second assistant director Michael Stevenson, an Englishman who had worked with Lean, Kubrick, and Anthony Mann, and holds Cimino in equally high esteem to those legends while also being the frankest of this bunch when it comes to recalling the difficulties of working with the demanding and temperamental director (as well as his significantly better rapport with actors, whom Cimino apparently valued highly).

--A TV advertisement for the film and, especially, its theatrical teaser trailer reveal how far the cult of the director has fallen since 1980: In the teaser, Cimino, in both name and visage, is featured as the "author" of Heaven's Gate even more prominently than the actors, something virtually unheard of unless you're Hitchcock, and a status even a Spielberg isn't quite granted in the promotion for his films.

--A prettily illustrated (with photos from the film), elegantly designed 40-page booklet featuring a new essay by film critic/programmer Giulia D'Agnolo Vallan and a reprint of a 1980 interview with Cimino for American Cinematographer magazine.

If Hollywood's 1970s second Golden Age of artistic creativity and freedom had to be killed off to make way for the slick, high-concept 80's, at least it died on an aptly glorious, elegiac note -- a fact that now, decades after the dust of Heaven's Gate's much-discussed, studio- and career-wrecking financial failure has settled, can finally be seen clearly thanks to this deluxe, conscientious new Blu-ray re-release of Cimino's nearly four-hour intended cut. The film tells the story, set in 1890s Wyoming, of a federal marshal (Kris Kristofferson) blessed with a keen moral sensitivity and cursed with an inescapably privileged background that sets him apart from the people he's trying to help, his enemy (the simultaneously sad and sinister Christopher Walken), and his friend/lover (Isabelle Huppert), as they are overtaken by and become embroiled in the repercussions of a wealthy, profit-mad stock-grower's association murderous crusade against the impoverished immigrants who want to farm the same land that could be lucrative cattle country (with a resulting epic-battle confrontation based on a real episode in American history, which Cimino here freely mythologizes). It's a story that Cimino allows to sprawl (and sprawl, and sprawl), but he earns that expansiveness; in this film, "sprawl" is well warranted, not synonymous with chaos or messiness, with Cimino very nearly pulling off his aimed-for complex, bloody, huge, multilayered encapsulation of all the contradictory things America means. In fact, what most distinctly marks Heaven's Gate (along with Vilmos Zsigmond's glorious cinematography) is its odd but striking, exhilarating symmetry, built up through its languorous pace and the patience with which it lets its breathtaking landscapes, intimate confrontations, and ferocious battles play out -- a languorousness, shared by many '70s films by Altman, Pakula, Coppola, et al., with their elongated and sustained narrative and visual interest, that would disappear with the much rapider editing in the '80s onslaught of blockbuster kids' movies, and of which Heaven's Gate stands as one last, defiant, towering exemplar.

It isn't a perfect film (though removing any awkward or overdone moments would have been ill-advised, leading to a disastrous, rippling domino-effect through the rest of the film and a collapse of its all-important structure, as shown by the butchered, extensively truncated version the studio forced Cimino to create for the initial run), but it is the kind of imperfect film that still overshadows most finer-honed or "tighter" but less ambitious rivals. It's also at least as relevant right now as it ever has been; it may have been too out of time for its own good in 1980, but in 2012, with the political mood encouragingly shifting away from the one that was on the rise when Heaven's Gate was released (we may finally be waking up from Reaganism; nothing ever "trickles down" of its own accord to poor/working/non-wealthy people, which any contemporary wage-slave knows from experience, and which the plight of the film's farmland-holding immigrants evocatively illustrates), right now is the perfect time for a second chance. That would be a chance afforded not by us to the film, but the other way around; it's we, the curious and soon-to-be-overwhelmed and ecstatic viewers, whom Cimino and Criterion have empowered to catch up from where wrongheaded popular opinion about the film has left us, we who are fortunate to have this opportunity, finally, to immerse ourselves in the unfairly reviled Heaven's Gate's melancholy, glorious light as it shines the way it was always meant to. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||