| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Last Days of Disco: The Criterion Collection, The

Please Note: The images used here are taken from promotional materials and the 2009 Criterion DVD edition, not the Blu-ray edition under review.

In his debut film, 1990's Metropolitan, it was magical the way writer/director Whit Stillman unexpectedly rendered so captivating and charming the humorous, touching postgraduate romantic peccadilloes of young, ultra-privileged Manhattanites in the fading, debutante-littered society world, with its balls and comings-out (of the non-gay variety). His ability to draw us into the post-Saturday Night Fever remnants of up-'n-coming-yuppie nightlife in the early Reagan years (for some of us, a uniquely unappealing-on-paper proposition) is even more surprising, really nothing short of miraculous. But there they are, his trademark hyperconversational, insecure, sometimes kind of jerky/bitchy, sometimes kind of brilliant/sweet, well-off white twentysomethings, most of them not too long out of college and struggling on the job/relationship market, sipping cocktails in lounge chairs and getting out on the dance floor. They're all of a piece with the funny, unpredictable, unexpectedly complex people from Metropolitan and Stillman's 1994 followup, Barcelona, who all, just by the nature Stillman has granted them, refuse predictability, stretching their own self-imposed limitations along with any that an outsider might assume goes along with their high(er)-income demographic -- demographics being only one among many topics to which our more well-read than experienced, eternally mulling protagonists apply their tentative but brave-faced stabs at wisdom.

So here, in what an opening title card cheekily informs us is "The Very Early 1980s - September," we have Jimmy Steinway (Mackenzie Astin), an advertising agent trying desperately to do his sycophantic job by getting his cheesy, badly-dressed clients into Manhattan's most exclusive disco (which is something like Studio 54, though it's never named in the film and acts as a sort of composite of New York's exclusive late-'70s disco palaces). The days of Mad Men are long over, and advertising and coolness have become antonymous; snobbishness has swung the other way now, and Jimmy and all "ad types" are banned from the club by its sleazy owner and snooty doorman (the latter played by future Igby Goes Down writer/director Burr Steers), leading him to lean on club manager/pal Des (Stillman stalwart Chris Eigeman), already on thin ice at his job and a coke-dabbling womanizer who gets rid of his (always female) sexual conquests when he tires of them by duplicitously claiming he's gay. Then there's Jimmy's once and future acquaintances/crush objects from their college years, Charlotte (Kate Beckinsale, Underworld) and Alice (Chloë Sevigny, Big Love), who both look fabulous, have evaded the ad-agency taint by getting publishing-world jobs as assistant editors reading through the sludge piles of unsolicited manuscripts, and therefore have no problem getting into the club. Rounding out this principal group of young-professional disco aficionados is Des's college acquaintance, Josh (the dashing Matt Keeslar), who's in love with Alice, has a history of bipolar illness that Des never stops rubbing in, and is now working for the Manhattan D.A.'s office, which puts him on a crash course with his musical and personal loves and loyalties when shady financial dealings put the beloved club under suspicion. Hovering around the edges of the main group are Alice and Charlotte's self-styled working-class-hero coworker, Dan (Matt Ross, American Psycho, The Aviator); their roommate, Holly (Tara Subkoff), and Alice's too-good-to-be-true longtime crush, Tom (Robert Sean Leonard), whose hidden but vituperatively sexist double standards are the least of what he has to inflict on the sheltered and naïve (and intent on hiding it) Alice.

Charlotte is no less sheltered and naïve, but she's aggressive: To Alice's "Forcing things never works" she assuredly rebuts, "That's not true. Forcing things usually works beautifully." She insists on her alleged, not at all self-evident friendship with Alice; insists that they and Holly get an apartment together; and insists on dispensing sometimes very insulting, falsely superior-sounding advice on relationships, taste, values, and getting ahead. There's a very flexible, fluid sort-of duality that forms here, with the Charlotte and Des characters -- devious and self-involved by nature, even if they think they want to have good intentions -- and Alice and Josh, vulnerable and sincere, who don't have to fight against their natures to mean well. It's to Stillman's great credit (though no-one familiar with his work will be surprised) that he makes either point of view easy to understand, right through to the end, and he doesn't leave any character bereft of at least some kindness and conscience (or, conversely, entirely free of egotism, self-righteousness, self-delusion, or other flaws). It's not anything so tidy as Josh and Alice and Des and Charlotte being parallel couples, either: Much dramatic tension and comical misunderstanding arises from the fact that nobody is sure who they're really drawn to or "should" be attracted to, or why; suffice it to say that none of the film's romantic pairings are necessarily permanent or follow a predictable path.

But in the special topography of Whit Stillman's world, plot machinations like the club's being under investigation are third-strata, and any diagram one could assemble of the character's shifting interrelationships are secondary; this is all well-conceived and structurally sound scaffolding upon which are festooned in abundance Stillman's classical talkie/talky film style, with its outpouring of quotable-dialogue gems. For example, Charlotte to faux-gay Des: "You're not fit to lick the boots of my real gay friends." Des: "I don't want to lick the boots of your real gay friends!" Josh to Des: "I consider you a person of some integrity. Except, of course, in your dealings with women." Des on his employers: "To me, shipping cash to Switzerland in canvas bags doesn't sound honest. To me, it suggests possible...illegality." Alice to Tom (acting on the bad seducing advice of Charlotte): "There's something really...sexy about Scrooge McDuck.... I love Uncle Scrooge." Andit's not only Uncle Scrooge who offers self-reflective fodder from the drawn/animated world for these introspectives; never before have people had so much to say about/read into Bambi or Lady and the Tramp (the latter of which provides a central romantic analogy for the film's "ladies" and "ruffians"). Stillman isn't mocking or merely making reference-happy postmodern confetti with these allusions, however; as overreaching, silly, incongruous, or even pathetic as they may sometimes come off, Stillman has a deep and abiding respect for his people's attempts to make some sense of or derive some meaning from their experiences, their culture, and the world they live in, which each of them in their own way hopes to try their hand at shaping.

The ratio of crowd(ed dancefloor) scenes to more typically Stillmanesque smaller-group/couple conversations in The Last Days of Disco is exponentially higher than in his prior films, and it's clear enough that he's working with his biggest budget and on his largest canvas yet (the biggest club in the biggest city!). But, thanks to the director's keeping together of his usual technical team (cinematographer John Thomas and editor Christopher Tellefsen), the film's overall feel is still intimate, dialogue-driven, classic, and classy (never ostentatious). Nobody, least of all the director himself, would mistake Whit Stillman for Martin Scorsese; his cinematic skill is less for flair, dynamism, or bravura than in a seamless integration of a calmly, subtly heightened reality with his not-quite-realistic but very real people (played exquisitely, I should add, predictably so by Stillman regular Eigeman but equally well by newcomers Beckinsale and Sevigny, who take swimmingly to their characters' preppie tones). The characteristic editing cut here, as in all of Stillman's films, is nearly or wholly invisible, unobtrusive; the characteristic images are medium shots of groups, a closer two-shot, or shot-countershot exchanges and/or individual close-ups with shallower focus, so that all the dancing extras are (or seem) blurred into background. (Even in the dance floor scenes, save for an atypical, memorably sweeping overhead/balcony shot from Charlotte and Alice's point of view and one rather irresistible, strobe-lit transition to the tune of Sister Sledge's "He's the Greatest Dancer," framing and blocking always put front and center the small handful of principals and whatever point they're at with themselves and in their relationships.) It's not until after the film's somehow perfectly gratifying, agreeable mostly-impasse of a conclusion (Stillman has by then removed any desire to see anyone get their comeuppance, and we're just glad they're all keeping on in their own ways, despite the group splintering and the last nail having been kicked into disco's coffin), in a bold and convincingly whimsical closing-credits sequence, that the film opens way up, suddenly and radically, allowing at least two of our heretofore lost and searching characters to join fully and unselfconsciously in the great stream of life. That big, open world is represented at this moment physically by a subway car surging forward and musically by the O'Jays' "Love Train," which might have made an apt alternate title for the film; with Whit Stillman as conductor, it's simply too infectious, and even in spite of yourself, you'll get pulled happily on board, too.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

The AVC/MPEG-4, 1080/24p transfer, presented at what is evidently Stillman's preferred aspect ratio of 1.78:1 (the theatrical AR was 1.85:1, a tiny difference I'm willing to accept from a director-approved edition), maintains a conscientious fidelity to cinematographer John Thomas's lighting and the film's subtle but strong color palette, all with the celluloid texture of actual film retained for a truly cinematic experience, with no deficiencies or video/compression flaws detectable at any moment.

Sound:The film's bounteous disco and R&B music, Mark Suozzo's score, and (just as importantly, if not more so) the sparkling dialogue emanate from your sound system with nary a false note -- no distortion or imbalance, ever -- on the Blu-ray's equally sparkling, full-bodied DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 soundtrack.

Extras:The new Criterion Blu-ray edition replicates exactly the grand buffet of supplements featured on their 2009 DVD release, including:

--An audio commentary track with Stillman, Sevigny, and Eigeman, that's simply addictive. All are affably opinionated and forthright, and each of them has their own particular impressions and experiences and versions of events, which they recall and share among themselves (and with us) in an honest but lighthearted, gently teasing way. The banter and recollections also include lots of juicy casting, studio/agent struggle gossip and we-can-laugh-about-it-now reminiscing on the "race" this film was forced into (by panicky studio heads and frivolous, buzz-happy media) with another concurrently-in-production "disco" contender, the now surely forgotten (and, at any rate, well inferior to Last Days of Disco) typical-Miramax offering 54.

--Four deleted scenes, well worth watching despite the rough shape they're in, that mostly deal with a little subplot about the "scabrous manuscript" kept by Des (Eigeman's character), in which he has evidently kept a record of his nefarious dealings with the opposite sex. With optional commentary by Stillman, Eigeman, and Sevigny explaining the whys and hows of these scenes' omission from the final cut.

--A brief promotional featurette that offers mercifully small portions of obnoxious, reductive narration and unexpectedly large doses of cast and crew discussing their characters and working with Whit Stillman, who also appears to discuss his own inspirations for and thinking on these characters at this time, both in their lives and in pop culture.

--A reading by Whit Stillman from his clever 2000 "novelization," The Last Days of Disco, with Drinks at the Petrossian Afterwards, written from the POV of the film's relatively minor character Jimmy Steinway, who has been asked to do a novelization of this disco film that has in part encompassed his experiences. Stillman writes and speaks remarkably like one of his half-self-effacingly loquacious characters, so this is the rare supplement that is a true extension in every way of the story we've been told through the film.

--A gallery of film and production stills, each introduced by an onscreen-text notation, commentary, or reminiscence by Stillman.

--The film's theatrical trailer.

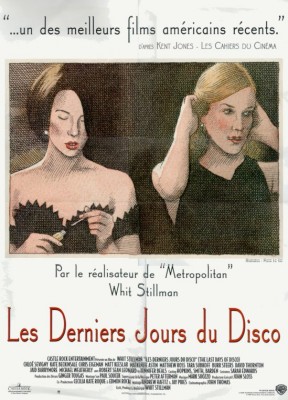

--A leaflet insert featuring an essay on the film by novelist David Schickler and lovely, supremely fitting colored-pencil drawings of Sevigny and Beckinsale's characters by Pierre Le-Tan, from his poster for the French release of the film (so superior in every way to the dull at best, misleading at worst campaign its U.S. marketers came up with).

It would sadly be almost another 15 years before Whit Stillman would make another film, but he topped off his excellent '90s comedy-of-manners trilogy of astutely and tenderly observed, well-off wittiness with a gracious, refreshing, understatedly substantive sparkle in The Last Days of Disco. The film's expansive but sharp characterizations and nonstop, brilliant verbal humor easily render it worthy of its two predecessors (1990's Metropolitan and 1994's Barcelona), and you don't have to harbor any nostalgia whatsoever for disco or early-'80s careerism to get all of the film's enjoyment; Stillman and his post-college, identity- and life-seeking characters are just as acutely charming, funny, and endearing whether or not you share the insular privilege they're all too well aware of or their taste for Chic. These characters debate themselves and each other, endlessly theorize and analyze, and do their often faltering best to put up a loquacious front in an attempt to fend off the fears, doubts, and sadnesses that nip at the heels and hearts of any entry-level twentysomething with big ideas/plans, searching all the while for whatever "romance" and "fulfillment" might mean to them (which is something they're not yet sure of). Stillman has by this point acquired full comfort and ease, all possible technical assurance in the classical filmmaking mode best suited to his world, and the period and musical trappings are all done just right, from clothes to décor. But that would all be pointless without the film's true, vibrant raison d'être, the beautifully rendered Stillmanisms -- the intellectual hilariousness, the hilarious intellectualism, the constant, clear current of sweetness -- that are here in such pleasurable abundance. He has a singular talent for capturing the exhilarations and letdowns of our species' fate as social creatures, and it's on full display in The Last Days of Disco, where his inimitable integration of humor, drama, and genuine, generous warmheartedness strikes a real blow -- without once cheating, sentimentalizing, or oversimplifying -- for the affirmation of life. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||